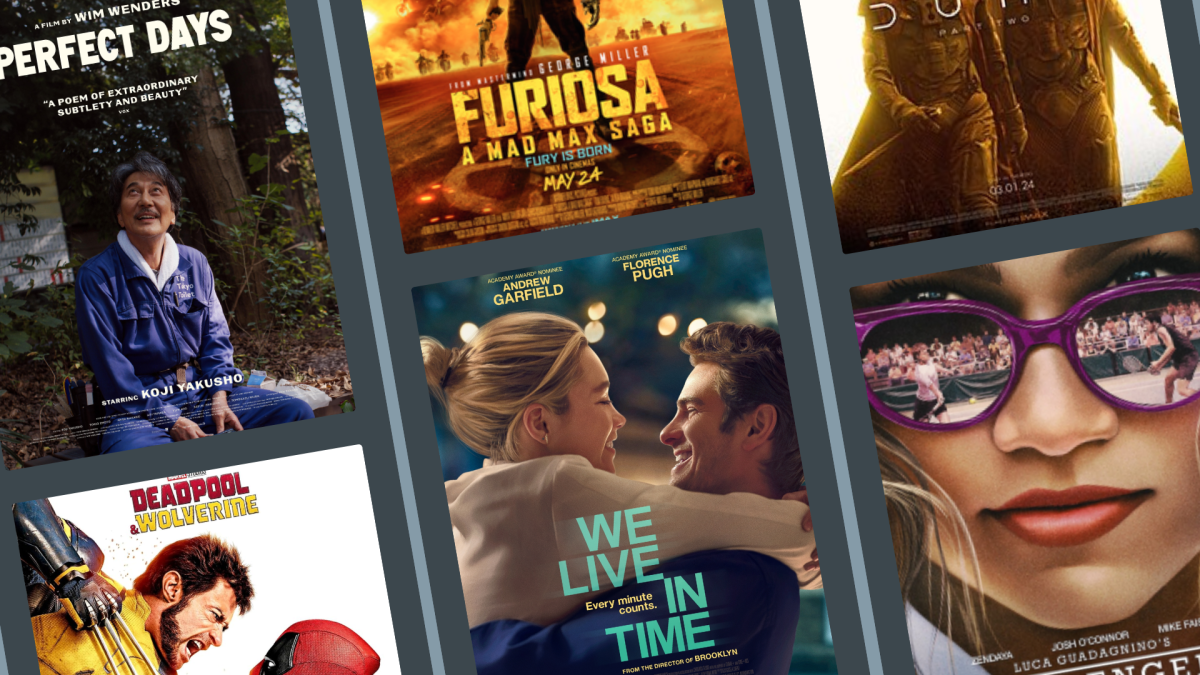

As an unnamed U.S. President addresses the nation in the opening scene of writer-director Alex Garland’s latest dystopian epic “Civil War,” we learn a few key details about the film’s nightmarish landscape. Texas and California have united to force the corrupt president out of office as the entire country has become embroiled in a massive and deadly conflict unlike anything the U.S. has seen since the 1860s.

It may sound like an outlandish scenario to some, but Garland seeks to turn this notion on its head, thrusting viewers into the bowels of a vicious skirmish between civilians and police on the streets of New York City just minutes into the runtime. Many have witnessed a riot of this scale on screen before, but the film’s raw depiction of violence makes for an especially startling watch. Part of what makes “Civil War’s” brutal portrayal of warfare so gravely compelling is that its action is not playing out in a far-off country or an imaginary sci-fi setting; rather, it takes advantage of most viewers’ familiarity with the landscapes and landmarks of the U.S. by showing them as we’ve never seen them before.

But in this early altercation between police officers and civilians, what captures our attention most is watching the events unfold from the perspective of photojournalists who make careers out of throwing themselves into every battle, determined to grab a lasting snapshot of a nation spiraling headfirst into a tailspin. Among this group is Lee Smith (Kirsten Dunst), an acclaimed war photographer, now beaten down and disillusioned with the cold reality of present-day America. Accompanied by her coworker Joel (Wagner Moura), Lee saves the life of an aspiring photojournalist, Jesse Cullen (Cailee Spaenee), from an unexpected suicide bombing.

From here, Lee, Joel and veteran journalist Sammy (Stephen McKinley Henderson) hatch a last-ditch plan to travel to Washington D.C. to capture an exclusive interview with the President. Never mind that the government is mowing down reporters on sight next to the White House grounds, the group is determined to make the treacherous journey into what will soon become ground zero for the war’s climactic final act. Much to Lee’s dismay, Jesse tags along as the group moves from one terrifying encounter to the next. After this point, Garland structures the plot around smaller story vignettes, which keeps enough of a flow to work for the story but undercuts some of the overall conflict’s larger stakes.

Thankfully, an especially talented group of lead actors ensures this never becomes a real problem. At the start of their journey, the cast effectively sells the dread and nihilism produced by the looming confrontations, and later, as they dive headfirst into further dangers, they play up the suffocatingly grotesque nature of an environment consumed by total war. But what makes those ideas so special is the film’s exploration of journalism during war, as supposedly neutral spectators become just as caught up in the conflict as the people fighting it. Garland pushes this idea to its furthest extent, giving Jesse and Lee two entirely opposing arcs that call into question the extent of their complicity in the violence waging around them.

In the past couple of years, the term “civil war” has become a buzzword in American politics, and Garland is seeking to dissuade those who flippantly throw the term around. As the lead characters wade deeper into an unpredictable wasteland of sheer terror, the true reality of a conflict of this scale becomes apparent, and the film makes it appallingly clear that no one on any side of the political spectrum would ever wish for an event like this to occur.

“Civil War” largely works because it’s concerned with the concept of war as a chaotic and disastrously unpredictable force that warps the reality of those caught in its wake. The film’s screenplay never bothers to expand the narrative or explain the broader context of the war’s outbreak because those details simply aren’t relevant to the story being told. And while the film certainly can’t be described as “apolitical”, it doesn’t seek to comment on the current partisan divisions in modern American politics or draw a parallel between recent events in the way that many initially assumed it would. Whatever that version of the movie would have been, it would likely be much less successful than the one we received. We should be thankful that Garland was smart enough to stay out of that hazardous territory.

While its grave thematic warnings are highly effective, the film occasionally oversimplifies some of its anti-war messaging into slightly simplistic moments compared to other high watermarks of the same genre. While “Civil War” leans more toward populist cinematic conventions and makes its themes very easily digestible, that isn’t entirely bad. In the end, the movie remains a wild ride.

Those who can’t stomach extensive violence or seek a film with more to say about modern American politics will likely be disappointed. But “Civil War” is a decidedly unique take on a war story that doesn’t closely resemble anything in recent memory. For that alone, the film deserves attention and is worth venturing out onto the frontlines to get a clear snapshot of.