Trigger warning: discussion of suicide, drug abuse and violence

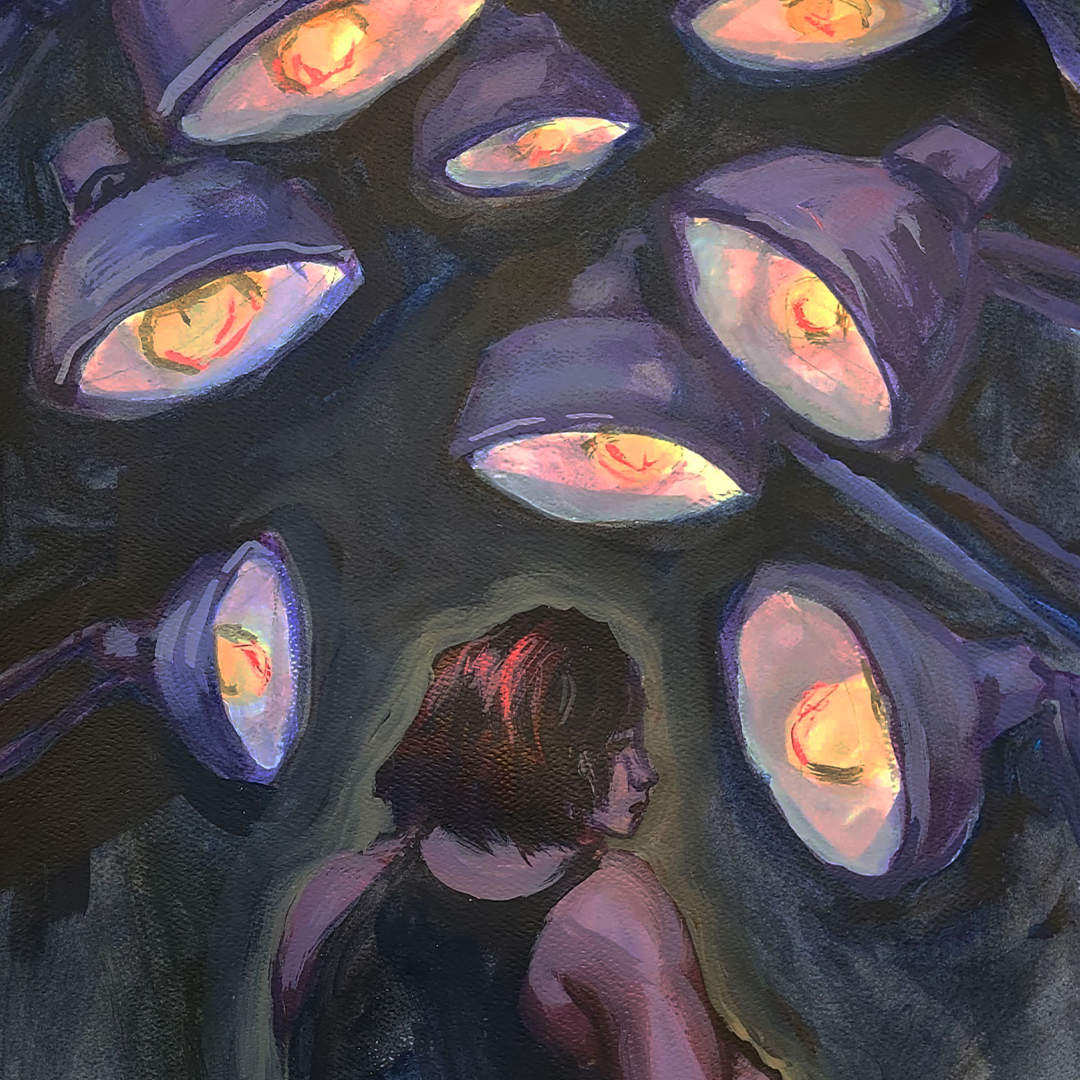

In the scenic mountains of Utah, worlds away from anything resembling civilization, lives a group of teenage girls. Bonded together by long hikes through the forest and poetry readings around the campfire, they are participants in Open Sky Wilderness Therapy, a program that seeks to “inspire individuals to live in a way that honors, values and strengthens relationships.”

This is not, however, a normal day: Katia, a participant in the program, has just swallowed shards of glass. In the midst of the girls’ panicked calls for help, Katia is airlifted out of the woods and transferred to a higher security institution. Staff members explain that Katia will not return to Open Sky — the program does not welcome participants who continue to endanger themselves.

When senior Sarah Eisel arrived in Durango, Colorado, in Mar. 2021, she never predicted that this sort of experience would characterize the next year of her life. After struggling with drug addiction and mental health challenges, Eisel’s parents decided to enroll her in Open Sky. Based out of Colorado and with many of its programs operating in Utah, Open Sky is one of a new movement of organizations that use an outdoor-based approach as behavioral intervention for adolescents and young adults.

In her first few days at Open Sky, Eisel saw newcomers experience severe substance withdrawals with little to no medical assistance. She watched Gracie, another teenage girl who would eventually become her close friend, suffer through Xanax and fentanyl withdrawals without so much as an Advil to ease her constant convulsions. The program’s unwillingness to lean on these intuitive interventions is the exact reason parents send their kids to Open Sky.

A week in, Eisel joined her “team” — a group of youth, pooled together based on similar concern and age — where she would spend the rest of her time in the program. Immediately, she felt like an outsider. Forced to intrude on a group that had been together for months and deprived of any contact with friends or family at home, an overwhelming sense of solitude defined Eisel’s first few weeks in Colorado. Exhaustion also set in quickly. Five out of seven days of the week, Eisel’s team participated in hours-long hikes, carrying heavy packs, unsure how long they’d been walking or how much further they had to go.

“My mental reaction first was just ‘how can I get myself out of here?’” Eisel said. “I was just trying to figure out every which way how I could get out, I needed to leave so bad.”

Eventually, things got easier. Eisel began to connect with other girls in the program and adjusted to the physical demands of her new daily routine. She found that Open Sky had succeeded in at least one aspect — she truly wanted to stay sober when she left.

Finally, in June, Eisel received the news she had been waiting for: in a week, she would be done with wilderness. After three months of exhausting daily hikes and nights spent on the forest floor, she was going to a therapeutic boarding school, Eva Carlston Academy in Salt Lake City, Utah. Eisel was elated at the prospect of having a mattress to sleep on, she said.

In the nine months she spent at Eva Carlston, Eisel felt mistreated and emotionally manipulated at the hands of staff members, she said. By the time she returned to Whitman in Mar. 2022, Eisel was sober and ready to stay that way, but she was also utterly traumatized by what it had taken to reach that point, she said.

Wilderness therapy programs and behavioral boarding schools like the ones Eisel attended are individual branches of the larger “Troubled Teen Industry.” The industry encompasses wilderness institutions, boot camps, boarding schools and behavioral ranches which look to address issues ranging from substance abuse and mental health concerns to “gaming addictions” and “social skills deficits.” The common factor that ties together these establishments is their strict approach to teenage behavior intervention — they work to fundamentally change participants’ ways of life.

While some programs implement the use of physical force, humiliation, starvation and other severe punishments to get through to participants, there are wilderness retreats that adopt a gentler approach. For Whitman youth development specialist Zakariah Anderson, experiences in wilderness programs helped him to rebuild his confidence. Following a difficult period in his high school career, Anderson spent three weeks at Outward Bound, a wilderness program located in Wales, England.

Initiated in 1962, Outward Bound held the goal of building survival skills and self-sufficiency for young boys to help them discover greater success. According to Anderson, programs like Outward Bound create a safe environment for individuals to broaden their perspective and connect to youth going through similar struggles.

“Once you sort of disconnect from not just your phone and all of these things, internet and whatever it is, and connect more with nature, you will find yourself to be a little more renewed and happier and having a greater sense of gratitude towards everything,” Anderson said.

Outward Bound’s model of cleansing through time in nature spread quickly to the United States, where copycat institutions soon populated the country. The ideology continued to gain momentum in the late 1960s, when Utah’s Brigham Young University began using rugged wilderness outings as a way to offer failing students an opportunity to salvage their academic career. From there, wilderness therapy took root in the rest of the state and spread into neighboring areas.

Utah’s status as the epicenter of the industry is also due to the specific state-level laws that dictate the way such programs can operate. In Utah, the age of medical consent is 18. Minors do not have control over what medical treatments they’re subjected to — that decision falls squarely on their parents, who maintain the right to send their child to a correctional facility if they see fit. Conversely, states like California and Washington have imposed regulations that favor individual choice; in California, minors ages 12 and older must consent to receive outpatient mental health treatment, and in Washington, the same applies for minors 13 and older. Because of these unique laws, parents across the country who feel the need to place their child in outsourced behavior modification programs tend to seek out those services in Utah, or other states with lenient restrictions on medical consent and medical guardianship for minors.

Wilderness Therapy’s no-nonsense approach to self-improvement is controversial in the world of healthcare. According to the American Psychological Association, ethical issues within the movement include consent, confidentiality and the treatment methods themselves.

Many programs advise parents to have their child unknowingly and forcefully taken to the program in a simulated kidnapping situation. Renee Farnet, who attended Open Sky with Eisel, experienced this approach firsthand.

“They grabbed me by the wrists and dragged me out of my house kicking and screaming,” Farnet said. “Then they shoved me into the car while I was fighting. They locked me in, and I started having a panic attack.”

This traumatic entrance to wilderness made Farnet’s adjustment period worse than it otherwise would have been, she said. Farnet was left constantly wondering why her parents would subject her to something so absurdly terrifying.

The programs continue to foster a divide between participants and their parents for the duration of their stay. Initially, this manifests through a complete ban on outside communication. As participants advance through their time in wilderness, they are allowed limited contact with their families. Employees warn parents in advance that their child will likely resist treatment at first, and may complain or exaggerate the conditions in an attempt to escape. When a child raises concerns or asks their parents to pull them from the program, the parent is already conditioned not to believe them. Eisel said this doubt often extended to the programs’ assigned therapists and staff as well.

“They went in with this mentality that I was not to trust, or to believe, or anything,” Eisel said.

Anderson’s wilderness experience differed in nearly every aspect. Within the first five days of entering the program, he felt well-supported and ingrained in the program’s mission of self-improvement. Anderson spent his time canoeing, hiking and rock climbing, finding the rigorous schedule comfortable, he said.

“I felt as though it forced me to create these bonds and forced me to work with people, help people and work as a team and to bring that self-confidence and self-esteem back,” Anderson said.

For adolescents struggling with their gender and sexual identities, current Troubled Teen programs’ conservative rules erred on the side of harm. While at Open Sky, Farnet began to question her gender identity, and changed her pronouns to she/they. When her therapist discovered this, she accused Farnet of wasting therapy time to discuss her gender expression. For other LGBTQ+ attendees, conditions were even worse, Farnet said. Transgender participants were also forced to use pronouns they would not identify with, despite the fact that they had transitioned prior to entering the program.

“At that point, I was kind of like, ‘Huh, this is low-key conversion camp,’” Farnet said.

Although they acknowledge the ways their lives have improved since they entered wilderness therapy, Eisel and Farnet both said that programs like Open Sky are an inherently harmful way to attempt to help struggling teenagers.

“I feel like there could be ways to make it better,” Farnet said. “But you know, it’s going to be traumatizing no matter what way you do it.”

Anderson believes that the government needs to pool more money and resources into wellness programs to further education in the field and decrease the stigma around mental health. Current concerns about abuse in rehabilitation programs are often dismissed as being a “natural part of the process” — breaking an addiction isn’t easy, and is practically guaranteed to take a deep emotional toll — but not every hurdle is natural. The lack of public support leaves a void these private programs fill.

“I felt like nobody really believed me,” Eisel said, “except my friends that I made there.”