Trading sorority sisters for cadets: female students’ experiences with service academies

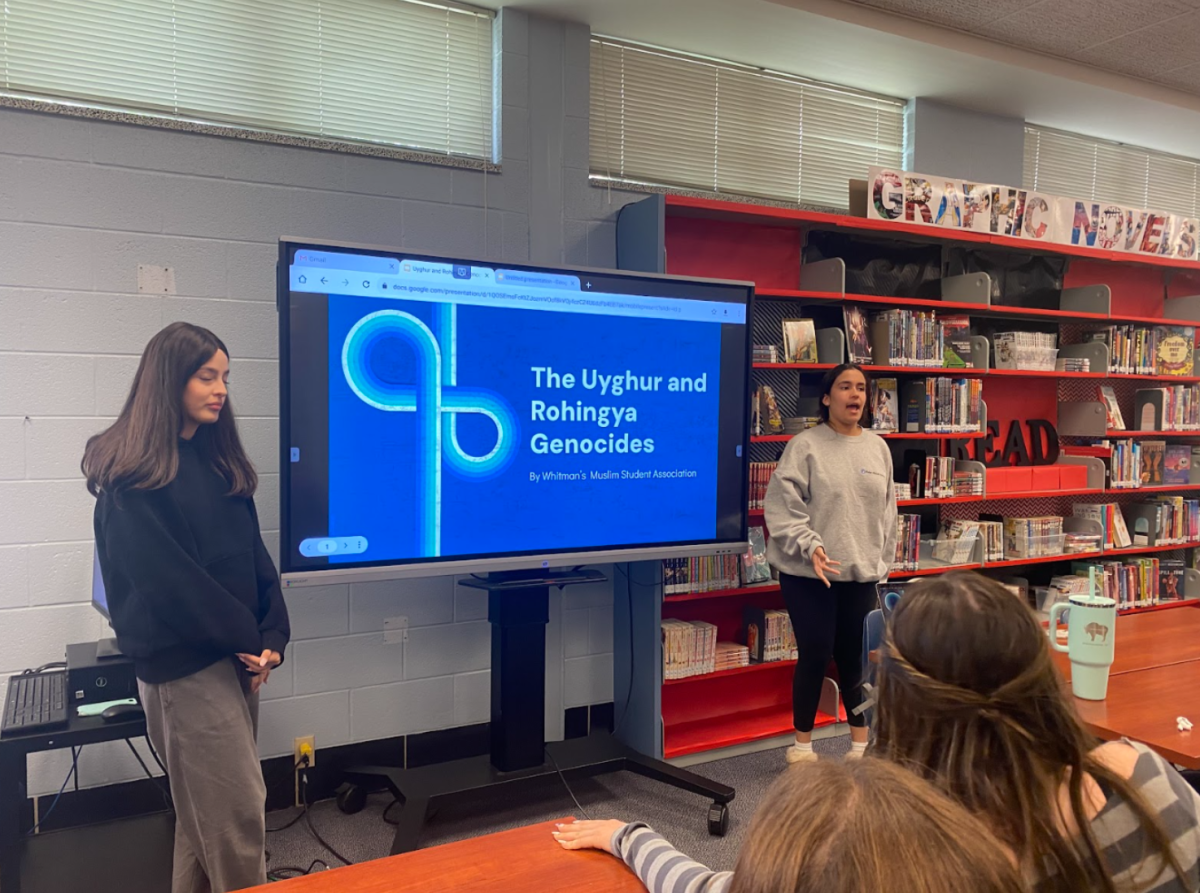

Photo courtesy Carleigh Armstrong

Cadet Carleigh Armstrong (47), who graduated from The Academy of the Holy Cross (’20), celebrates during a Westpoint Lacrosse game.

September 14, 2021

This story was published in print during the 2020-21 school year.

A typical Whitman senior might spend their summer lounging by the pool, working at a summer camp or taking trips to the beach before heading off to college in the fall. But for senior Ida McLaughlin, the final few weeks of adolescent freedom will be anything but relaxing.

On June 26, McLaughlin will report to the United States Military Academy — also known as West Point — for Cadet Basic Training, or what they call “BEAST Barracks.” Every day for six weeks, McLaughlin will wake up at 6:00 a.m. sharp for extensive military training to prepare her for enrollment at the prestigious military academy.

As a child, McLaughlin was always inspired by her relatives in the military — an aunt and two grandfathers who served in the Army and Navy. When college application season rolled around, it was no surprise to McLaughlin’s family that she was interested in serving in a branch of the military.

“Both of my parents were super excited and supportive when I told them that I wanted to apply to a service academy,” McLaughlin said. “My dad was the one who pushed me to finish my application to the Military Academy because he thought that it would be a good fit for me.”

At West Point, McLaughlin intends on majoring in mechanical and aerospace engineering while also rowing for the crew team. However, unlike students at most four-year universities, McLaughlin will also be training to become a future military leader; she hopes to be commissioned as a second lieutenant for the U.S. Army following graduation.

“For some people, going to college and getting an engineering degree is exactly what they want,” McLaughlin said. “I thought that I could do that, but I wanted to take it a step further and do something to help others.”

Federal service academies, including West Point, each have a unique and rigorous application process. Applicants formally begin the process during their junior year, McLaughlin said. In addition to submitting high school transcripts and standardized test scores, applicants must be interviewed by an admissions representative with military experience. If an applicant is deemed fit for the academy during the interview, they progress to the next stage in the process, where they must obtain one of the limited congressional nominations in their state.

“I did underestimate the application process,” McLaughlin said. “There were so many steps within obtaining a nomination and different people to contact, that it was overwhelming at times.”

At any time, a maximum of five admits nominated by any given member of Congress may attend each academy. For each slot vacancy, a congressman may nominate up to 10 new applicants for consideration by each academy. The Naval Academy, located in Annapolis, produces a large pool of service academy applicants each year, making nominations from Maryland’s members of Congress especially competitive. McLaughlin had to submit around 20 short essays about her extracurricular activities and academic pursuits to each congressional representative. The congressmen then narrowed the application pool down and invited each applicant to another interview with a panel of qualified military personnel. McLaughlin applied for nominations from both of Maryland’s state senators and a state representative, ultimately obtaining the nomination from Rep. Jamie Raskin. Each academy then admits the nominees whom they believe will best fulfill their admission requirements.

Beyond the rigorous required paperwork and interviews part of the application process, female applicants face the added hurdle of gender disparity.

50 years ago, McLaughlin wouldn’t have been able to apply to West Point — they didn’t admit women until 1976. Although service academies have slowly seen a rising number of female students, the gender gap within the school is still a prevalent concern, McLaughlin said.

“At first I was hesitant to apply because of the overwhelming ratio of male to female cadets,” McLaughlin said. “But that worry went away after getting in touch with alumni at service academies who reassured me that I will have the same opportunities as the male cadets.”

According to a 2019 study by the Connecticut Veterans Legal Center, members of the 116th Congress — sworn into office in Jan. 2019 — nominated far more men for service academies than other applicants, with female students making up only 21% of congressional nominations, despite the fact that they represent roughly a third of the total applications for each academy.

Service academies are exempt from Title IX, which prohibits all forms of sex-based discrimination in education. The academies haven’t offered a clear explanation to the reasoning behind their exception from these policies, but data show that the exemption has led to gender inequalities within the service academies and their application process, McLaughlin said.

“You hear these stories about women in the military that are facing inequalities because of their gender,” McLaughlin said. “I want to change that culture and become a trusted leader for my enlisted personnel.”

After McLaughlin obtained a nomination, she had to complete the Candidate Fitness Assessment, or CFA, which predicts an applicant’s aptitude to handle the physical requirements of the service academies. The assessment consists of cadence pull-ups, sit-ups, push-ups, a 40-yard sprint, a one-mile run and a basketball throw, where applicants must kneel with both knees on the ground and throw a basketball as far as they can with one hand. McLaughlin completed the CFA in the spring of her junior year.

“Everybody I’ve talked to agrees that the basketball throw is only in there so that they can see who’s actually committed to working on these events,” she said. “The farther that the basketball travels, [the more] it shows that you’ve dedicated yourself to practicing the skill.”

Every year, the academies release a document that outlines the average CFA scores for each event and gender. The applicant’s raw scores from each event convert to a point scale that ranks their performance against the performances of their peers. The CFA and other unique aspects within the application discourage many students from applying, McLaughlin said.

Even after applicants complete these exhaustive requirements, they’re far from a guaranteed acceptance. According to the National Center for Education Statistics, out of the 41,989 applicants to the five military academies for the class of 2023, only about 4,100 candidates were accepted, producing an acceptance rate of 8% — comparable to that of universities like Dartmouth and Duke.

At Whitman, applying to service academies isn’t common: in the past five years, only 24 students have applied. Of those students, only six have attended, half of whom were female.

When a student enrolls in a service academy, there is a greater level of commitment expected than of many other collegiate paths; each academy requires five years of active duty after graduation. West Point and Air Force Academy graduates serve an additional three years in the reserves, where soldiers are able to live close to home while continuing military training.

Cadet Carleigh Armstrong, a graduate of The Academy of the Holy Cross (‘20), plays for the West Point women’s lacrosse team. Armstrong is a “plebe” — the West Point equivalent of a freshman — and comes from a long line of Naval Academy graduates. Although she had mild interest in attending a service academy after high school, she never thought that she would follow through until she got in touch with a West Point lacrosse recruiter, she said.

“When I was trying to figure out what I wanted to do after high school, I reached out to a coach at West Point because I figured that it couldn’t hurt,” Armstrong said. “The fall of my junior year, I came to the campus for an unofficial visit and instantly fell in love with the academy.”

On a typical day, Armstrong wakes up at 6:20 a.m. to complete chores such as mopping the halls and taking out the trash before formation, one of many cadet meetings throughout the day. During formation, cadets assemble into uniform rows for a variety of exercises and training. Following breakfast, she heads straight to her classes. At West Point, students can choose to take a variety of courses, ranging in focus from academics to athletics to combat training.

“One of the more interesting classes that I took this year was ‘plebe’ boxing,” Armstrong said. “Even though I got punched in the face at 7 a.m., it was a super cool class that taught me a lot that I can use in the field.”

At West Point, women make up less than 20% of the student population. Despite the lack of female students around her, Armstrong feels empowered by her minority status, she said.

“I think that many high school girls are discouraged from this route because they think that being a woman in a predominantly male-dominated profession is a hard challenge to overcome,” Armstrong said. “The Academy does not tolerate any form of inequality towards women and the encouragement that I get from my male counterparts is enormous — they’re some of my closest friends.”

Armstrong and McLaughlin both agree that life at service academies does not resemble a typical college experience. There are strict restrictions on alcohol, drugs and parties, and Greek life is absent. Still, they agree that the service academy route is a rewarding path to take.

“I can’t imagine going anywhere else for college,” Armstrong said. “West Point has been such a great experience for me, and I can’t wait to see what comes next.”