Being Multiracial: 51 years after Loving v. Virginia

June 12, 2018

When they saw us, they stared, glared and goggled. They were passing customers at a Wegmans supermarket in Northern Pennsylvania, and I was shopping with my family. I remember fidgeting nervously as their eyes tracked my siblings and me throughout the store. I was 12, and this was the first time I’d explicitly noticed the judgemental looks and condescending glances that came with being the child of a mixed-race marriage.

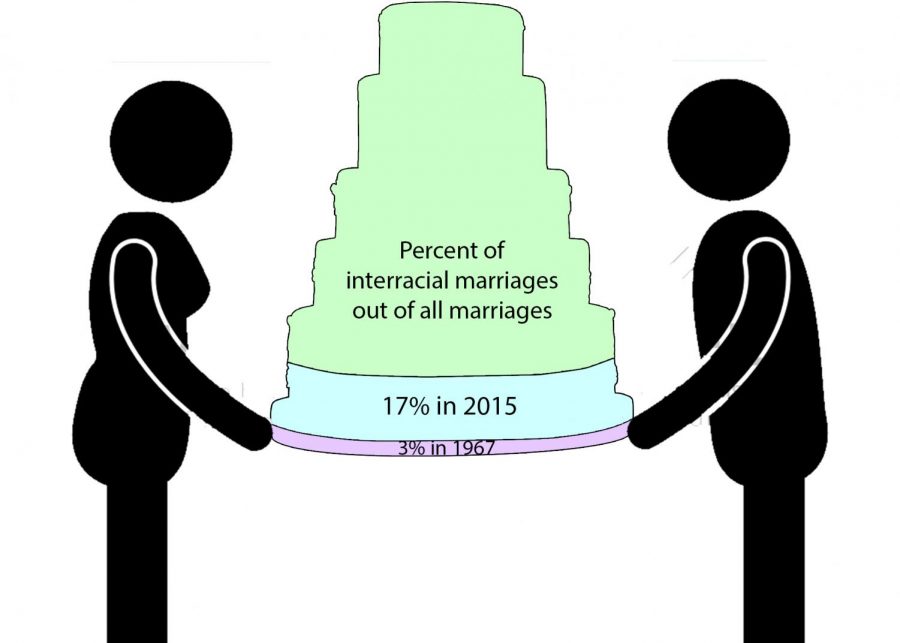

The U.S. Supreme Court historically ruled in the 1967 case Loving v. Virginia to decriminalize miscegenation, or the marriage of two people of different races. This ruling overturned the precedent established in 1883 in Pace v. Alabama, which stated that anti-miscegenation laws didn’t violate the 14th Amendment of granting equal protection under the law because all races received equal punishment for the crime.

We’ve come a long way since then in terms of numbers; 17 percent of marriages were mixed race in 2015, according to the Pew Research Center. But for interracial families to truly be accepted by society, there’s still a lot of work to be done.

The history of miscegenation in the US isn’t included in standard history classes, including the MCPS required curriculum. Teaching about the struggle for interracial marriage rights is necessary to understand the context of modern day discrimination and the complexities of identity. When this topic isn’t made a priority, it breeds ignorance.

Not long after the Wegman’s incident, my mom told me that her parents practically disowned her for marrying my dad, who’s black and not Italian Roman Catholic like her family. While the tension has eased over the years, my grandparents will only speak to my dad on the phone, not in person.

Outside of my family, I’m disturbed by microaggressions targeting mixed-race relationships in casual conversation. When I hear people talk about how they want their kids to be a “cute mix,” or when people tell me that my puffy, curly hair makes me look “like a dog,” it dehumanizes my identity. The lack of awareness that this type of speech is both offensive and alarming.

Being multiracial is something I take great pride in as a half-Italian, part-Jamaican, part-Chinese and part-Cuban teenager. And I’m not alone; there are millions of multiracial people who face discrimination every day. It’s time we turned the de jure ruling of Loving v. Virginia into a de facto reality.