‘More than just an incident’: One year after initial racist graffiti, community continues to push against prejudice

Advocates gather during the student-led Black Lives Matter demonstration in Bethesda on June 2. Since the protest, many students’ “willingness to learn” has pushed others to become more tolerant, said senior Lily Muchimba, who helped organize the event.

April 1, 2021

When senior Tatiana Johnson reflected on her time at Whitman before the building closed last March, she felt classmates sometimes labeled her “loud and Black” during conversations. In her classes, people occasionally picked on her for being the only Black student in the room. And sometimes, when Tatiana asked her teachers questions, they imitated her — “like how, quote unquote, a Black person speaks,” she said.

This past spring, however, some of Tatiana’s classmates started reaching out to her. In the wake of several prominent racial incidents — some nationwide, some close to home — a number of students realized that they had previously carried out hurtful microaggressions, they told her. They apologized, and added that they were educating themselves on how to avoid committing offensive acts in the future.

“I was like, ‘wow,’” Tatiana said. “It made me feel like we’re getting somewhere, because people are actually looking back, thinking about what they’ve done in the past and taking accountability for their actions.”

This March marks one year since a Whitman student spray painted racial slurs, language relating to lynching and a depiction of a noose on a wall near the school’s tennis courts. Three months later, the MCPD arrested that student and two others in a second, nearly identical incident of racist vandalism on June 13.

Tatiana and other students said that although the Whitman community is still far from being a completely inclusive one, the environment has improved from where it was a year ago — not necessarily in tangible ways, but because of many students’ increased “willingness to learn,” as senior Lily Muchimba put it. Muchimba and Tatiana were among several students who organized a Black Lives Matter demonstration in Bethesda during a nationwide surge of protests during June of 2020.

“With the incident happening last year, I need to be honest — I feel like people are trying more; they show up,” Muchimba said. “I think the encouragement of wanting to be a part of something big and on the right side of history impacts a lot of kids.”

Muchimba has especially seen this change come into play in her role as Vice President of Whitman’s Black Student Union, she said. The Black Student Union has held several events this year for students to learn about and discuss Black history. The conversations have hopefully helped open attendees’ minds to issues of race, Muchimba said.

Senior Joseph Kaplan, for one, said he “really, really enjoyed” one particular Black Student Union lecture about the Black Panther Party, and that the group’s subsequent open discussion was incredibly eye-opening.

“I think that the last year has had a huge impact on the way that everyone has these conversations,” Kaplan said. “That’s what I’ve been trying to do, is just be aware at all times and be listening at all times. If you can exert a little extra mental energy and embarrass yourself just a little bit and not worry about your pride, I think that’s where you learn the most.”

Tatiana has also seen students work to educate themselves about combating hatred — particularly through OneWhitman, the school’s hallmark anti-bias initiative.

“The people who come to it really put in an effort to try and help the Whitman community,” said Tatiana, who helps coordinate the program as a student facilitator. “We’ve been making strides to success.”

When OneWhitman began in September 2019, the program consisted of compulsory weekly seminars that significant portions of the student body either declined to participate in or even skipped entirely. The program received negative feedback, not just from students but from some staff members, said OneWhitman planning committee member Alicia Johnson, a resource teacher.

“People were saying, ‘I don’t want to be vulnerable in front of my students this way,’ or ‘I don’t come to school for this’ or ‘This shouldn’t be part of my education,’” she said. “It was unfortunate, and we got a lot of pushback sometimes during our survey that we were doing on a quarterly basis.”

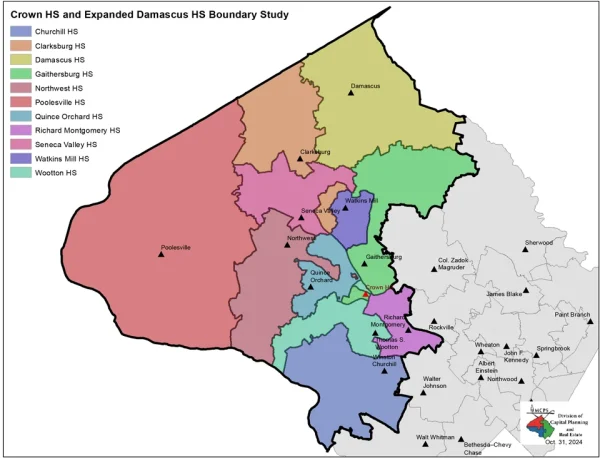

After the June graffiti incident, however, administrators made several modifications to OneWhitman’s structure. Student facilitators now play a significant role in formulating and leading the virtual seminars, and organizers tailor lessons to emphasize specific subjects, rather than focusing on abstract topics. This year, participants have examined hip hop culture, housing segregation in the D.C. area and the influence and role of historically Black colleges and universities. This stands in contrast to last year, when students spent one morning pondering which “equity area” resonated most deeply with them.

OneWhitman is also no longer mandatory, which student facilitator Austin Mboijana, a junior, described as a “major improvement” from last year. Students’ engagement with other attendees who actively want to be a part of the program has heightened their willingness to participate, Mboijana said. A few hundred of the school’s roughly 2,000 students typically attend each OneWhitman session.

“Kids who want to do better are getting the resources to improve themselves and work to be anti-racist and just become better human beings in general,” Mboijana said.

Of course, these efforts aren’t always easy; many attendees are often hesitant to speak up during sensitive conversations, said student facilitator Felipe DeBolle.

“For me, for a lot of issues, it’s hard for me to talk about them without getting somewhat emotional,” DeBolle said. “I think that a lot of students don’t want to get emotional or don’t want to open out and be super vulnerable. All of these conversations are really hard conversations to have, and you need to think clearly about some really deep issues.”

Listening to teachers’ contributions in OneWhitman breakout room discussions has led Tatiana to believe that many staff members have even further to go than students in terms of equity training, she said.

“Teachers sometimes are still kind of standoffish, like: ‘Oh, I don’t know about this, so I can’t say anything on it,’” she said. “Sometimes I feel like they don’t really try.”

After the June vandalism, dozens of current and former SGA representatives called on the Whitman administration to expel the accused students, two of whom were rising seniors. The Black & White could not reach Whitman administrators for comment on whether the school took disciplinary action against the students.

Even so, SGA President Kushan Weerakoon said that many students’ attempts at vulnerability during programs like OneWhitman matters more than the school’s potential lack of punishments toward the accused vandals.

“We just can’t forget,” Weerakoon said. “Make sure that this is not a one-year thing. And continue to learn, because no growth happens without the willingness to be vulnerable and to learn.”

Mboijana said that gauging how much progress the community has made won’t be fully possible until Whitman students return to the school — over Zoom, students are unlikely to commit overt acts of racism, “to make some insensitive joke in front of a teacher and unmute themselves,” he said.

Not all students will push themselves to help eradicate hatred in the community into the next year, but Mboijana said he’s already seen signs of growth.

“Of course we can be wishful thinkers and say that this will all go away and everybody will treat everyone the same, no matter what they look like, where they’re from or how they speak,” Mboijana said. “I don’t think that’s realistic. But I’ve seen a lot of students who are willing to hear different perspectives and be educated, and are willing to advocate for equal opportunity and the elimination of systematic racism. That brings me hope.”