Don’t just do lip service to the idea of anti-racism, amplify unheard voices in literature

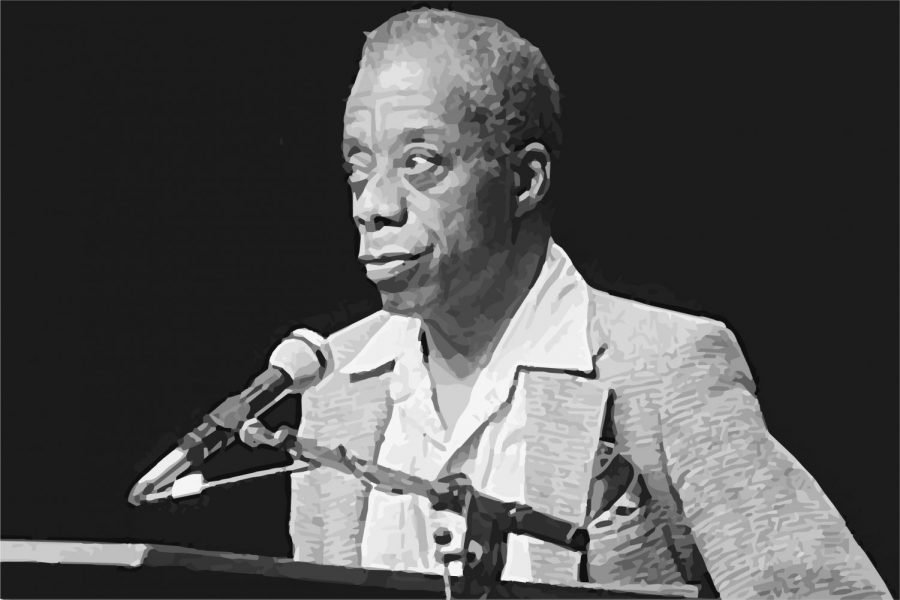

Black author James Baldwin

November 18, 2020

In light of the murders of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, Ahmaud Arbery and countless other Black Americans, Whitman’s AP Language and Composition teachers assigned their students, including myself, to read The Fire Next Time by James Baldwin, Between the World and Me by Ta’Nehisi Coates and The Other Wes Moore by Wes Moore over the summer. All three books are scathing first-hand accounts of the Black experience in America.

The lessons learned from these books are steps towards a more tolerant county, state and country. Other Whitman English teachers should follow the lead of the AP Lang team and incorporate diverse literature into their curricula. Such efforts can enlighten students to the minority experience and the injustices of the world around us.

Reading first-hand accounts of the lives of marginalized groups in America not only ensures that students are aware of racism, but helps them actively fight it, said Christina Torres, an English teacher at the Punahou School in Hawaii. She recommends books such as How to be an Antiracist by Ibram X. Kendi and White Fragility by Robin DiAngelo to help students become aware of their implicit biases. Such works of literature can transform society into a place where race is not one’s defining characteristic, Torres said.

In my experience, reading first hand accounts of the Black experience in America has helped me better understand the societal barriers that Black Americans face. From Baldwin and Coates’ narratives, I learned that the minute children of color in our country become aware of their surroundings they feel as if they are inherently inferior in the society which their ancestors struggled to build. I learned that the white American hierarchy depends on subjugating African American people and how people find it all too easy to overlook injustice because to admit that the system is broken would be to lose their power.

Before reading these books, I was aware that communities of color were discriminated against by the institutions in our country, but these pieces of literature widened my perspective on how discrimination effects people’s self-perception. Statistics can quantify how many Black Americans are disenfranchised by corporations and institutions, but these numbers can’t reveal the lived experiences of people of color. Reading first-hand accounts provides an emotional depth that plain data lacks. It allows us to empathize with their pain and motivates us to act.

In the classroom, minority literature not only opens up non-student of colors’ eyes to the injustices faced by minorities but can also make marginalized groups feel like their voices and stories are being heard. Growing up as a minority in the United States, I can vouch for the fact that solely reading white narratives makes minority students feel invisible. It’s extremely difficult for us students of color to relate to the stories being assigned in class. This sense of not belonging leads minority students to believe that the only stories worth telling are those of white Americans. It plants the idea that nobody is interested in learning how their families live or what their customs and beliefs are. Reading minority literature in class erases this feeling of invisibility; it advances the cause of anti-racism and helps every student feel like they have a place in their school.

For us Whitman students to be empathetic and, by extension, anti-racist, we have to listen to the stories of disenfranchised groups. Fighting racism is not an easy task, but we have to continue working hard. Implementing minority literature into the English curricula is a meaningful way to continue this fight. Together, we can become more aware of what’s really going on in the world around us.