Embrace the mystery of black holes

February 4, 2019

In fourth grade, a friend told me that the Earth would eventually get sucked in a giant black hole and we would all die. I cried. Then I asked what a black hole was; he didn’t know. Then I cried some more.

Determined to find out what black holes were, I did a little research when I got home. Since then, my interest has shifted from fear to fascination. It’s not because I’m obsessed with our doom; in fact, if that’s the way we go, I’d rather not know. It’s the mystery surrounding the black holes that intrigues me. We may never know what’s on the other side—it could be a parallel universe, a dead end or a boundless void.

NASA describes a black hole as “a place in space where gravity pulls so much that even light cannot get out.” Of the estimated 100 million black holes in our galaxy, some are as small as an atom, but have the mass of a mountain, while others have the mass of over 1 million suns, or 300 trillion Earths. A “supermassive” black hole, as scientists call them, lies at the center of the Milky Way galaxy, called “Sagittarius A.” Despite its ominous-sounding name, Sagittarius A is not going to destroy our planet. It’s simply not close enough for its gravitational pull to affect us.

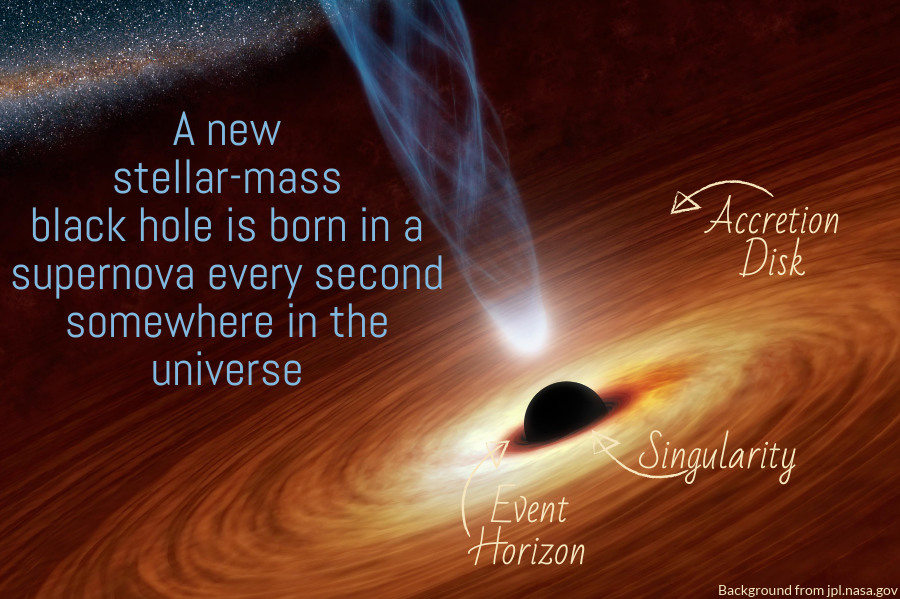

To properly explore black holes though, we have to go back to the beginning of the universe. Let’s go on an adventure. In a Ms. Frizzle-like fashion, we zip up our space suits, file onto our magic bus and stare out the window as we fly back in time. Once we reach our destination, we hear a bang and the universe is formed. Time starts ticking, and the universe begins to grow. Tiny, primordial black holes appear right away, and later, as galaxies emerge, “supermassive” black holes form at each center. Many years pass, and stars grow old and collapse. In the wake of these supernovas, we see the third type of black hole form: stellar black holes, which, sizewise, are anything from 10 to 100 solar masses. Most of the black holes in the Milky Way are stellar black holes, scientists have discovered.

Our bus begins to approach this new kind of black hole, which we’ll name “Todd” so we don’t have to refer to it as “black hole.” Like most black holes, Todd spins, and we get dizzy as we enter. Because of his massive gravitational pull, Todd distorts space and time in his surrounding area. Time actually passes slower as we get closer, and, far inside, we see the densest, smallest part of a black hole: the “singularity,” or where space and time stop entirely. If the singularity explodes, some scientists believe it could create a universe. With a bang. Sound familiar?

Scientists theorize that our entire universe came from the tiniest seed inside a massive, light-sucking force, where neither space nor time exists but apparently a universe exists and my brain hurts oh my goodness I think we need a breather. Go stretch. Get a glass of water. We’ll regroup in a few.

Alright. I hope you’re happy and hydrated. We still haven’t learned everything there is to know about black holes. But we don’t need to. In fact, I’m perfectly content with not knowing. We’re always so concerned with finding solutions, uncovering explanations and learning everything there is to learn that we forget to enjoy the little moments, like finally going home after a long field trip. We should be able to appreciate the mysteries of the universe without stressing over why, why, why.

By some miracle, our bus exits the black hole. We zoom past Todd’s outer rim, known as the “event horizon,” or “the point of no return,” and pick up speed as we drive farther and farther away. We have stopped spinning; the bus touches down onto earth. Our planet is still intact, unaffected by the black holes in our galaxy. We go home and soon get caught up in our everyday routines.

But I hope you learned something from our adventure. Or not. I’ve told you all I can about black holes, and I don’t want you to worry over not knowing how an entire universe can come from a speck in space. Really, I just hope you had fun. I know I did.