Junior Olaf Hichwa propels into drone racing, sponsorships

In the the Northeast Regional Finals in New York this August, Hichwa (left) places 3rd out nearly 100 competitors. Competitors who place in the top 12 in regional finals are guaranteed a spot in the national drone championship. Olaf called the race “the best race of “his life”.

January 25, 2019

Junior Olaf Hichwa hates gravity. He can’t remember a time when he wasn’t interested in aviation. As soon as he could talk, he told his parents he wanted to be a pilot when he grew up. So when he was six years old, his parents bought him a remote control helicopter.

He flew it every day until it broke.

The helicopter was too slow for him, so in middle school, he began flying high-speed helicopters he built himself from kits, but even that didn’t satisfy him. So when he saw an advertisement for drones on a poster at the hobby store where he regularly got his helicopters fixed, he knew he had to get his hands on one.

Today, when he looks up at the sky, he remembers the euphoria he felt when he rode in an airplane for the first time. But on the ground, he feels the constant “burden” of gravity on his shoulders, pushing him down. Since he started flying drones, he said he’s recaptured that euphoria once again.

“I’ve always looked at the sky and thought, ‘woah.’ I feel like it’s always been something I can’t do: I can’t go up,” Hichwa said. “I hate gravity. Drones let me feel like I’m in the air.”

Remote-controlled aerial vehicles, drones have four propellers and complex circuit boards that allow them to fly. More than 670,000 people registered their drones with the federal government in 2016. That number topped one million in 2018, reported the Federal Aviation Association.

In recent years, drone racing has become popular. While consumer drones can only go a maximum speed of 50 miles per hour, racing drones can sometimes exceed 120 miles per hour. One of four prominent racing leagues in the US, the Multi-GP Drone Racing League, has more than 10,000 registered pilots.

Hichwa has traveled as far as Louisiana and Nevada to compete in races with drones he builds himself.

Racing is divided into two categories: spectator-based and pilot-based. Hichwa races in both. The normally indoor spectator-based courses focus on entertainment value by incorporating elements like smoke, rings of fire and black lights. Competitors in pilot-based courses are focused primarily on winning. These races typically take place in large fields or open outdoor areas where speed trumps theatrics.

Hichwa bought his first drone, the Blade 350 QX, one of the first drones available on the consumer market, in 2013. The drone is large and bulky, so it can hover but not fly forward.

Hichwa cools off with fellow competitors before the Open Grove Callout, a drone race in California this April, by spraying compressed air at each other. Hichwa competed wearing a jersey from his sponsor, Pyro-Drone, which creates a variety of drone parts including batteries and motors for drones.

When pilots are racing, they wear goggles similar to virtual reality goggles, which display live footage of the drone’s point of view as it flies—or “first person view.” He improvised this first person view by attaching a camera and antennas to the drone with electrical tape and connecting the drone to a pair of goggles via a video channel.

After 400 hours spent flying the drone, Hichwa now flies, repairs and researches drones every day. He said his interest in drones isn’t a hobby; it’s an “addiction.”

“My addiction is my passion. It’s just natural. Every second that I’m awake, I want to be doing something with drones,” Hichwa said. “Every second I’m doing school work, I just want to get it done—that way I can get to drones.”

Hichwa finished building his first drone in 2015. After connecting with other pilots on Facebook and watching livestream videos of them competing, Hichwa decided he wanted to enter a drone race.

He had never competed in anything before. As a kid, he hated every sport he participated in. But unlike sports, drone competitions excited him.

Last year, after two rounds of regional qualifying races, Hichwa competed at his first national tournament, the U.S. National Drone Racing Championship, where he placed 96th out of 117 competitors. Although he was unhappy with his results, he was overwhelmed by how welcoming the drone community was, he said.

So he decided to race again.

When he placed tenth out of nearly 120 people in his next national tournament, he realized drone racing was something he wanted to do for as long as he could.

“I was so surprised that I was flying that well. I was shaking. I had no idea what was going on. I even had a drone catch on fire during the race,” Hichwa said. “That was the moment that I realized racing is for me.”

After he placed in a few races and posted often in drone-related Facebook groups, several companies that specialize in drone parts reached out to Hichwa to sponsor him. Now, PiroFlip, which sells nearly every drone part, including frames and motors; China Hobby Line, a battery company; HQ Props, a propeller manufacturer; and Foxeer, which sells cameras and antennas, all sponsor Hichwa.

Maintaining sponsorships is time-consuming. He’s constantly advertising his four sponsors’ products on his Facebook account and has to wear apparel with their logos during competitions. But thanks to his sponsors, Hichwa only has to buy around half the parts he needs for his drones. For competitors without sponsors, maintaining drones for races can cost upwards of $1,000 a month, he said.

“I’m super thankful, but it’s a lot of work,” he said. “It’s not like I get free stuff falling from the sky for doing nothing. I have to do a lot for the stuff I get.”

Hichwa likes to spend his Friday afternoons at Drone Club’s weekly meeting. He started the club to share supplies with other drone enthusiasts and teach anyone willing to learn about drones, he said.

“I have a lot of old gear sitting around and I love flying with new people,” Hichwa said. “I decided I might as well put it to good use and fly with new pilots.”

Hichwa said he wants the club to be a place where people can make friends but also learn basic mechanics. During one of the first meetings of the year, he gave out handwritten notes to all the members to help them understand the mechanics, engineering and physics of drones.

“I think drones have a tremendous ability to teach people really complex subjects and make it fun,” Hichwa said. “No one wants to learn all these engineering subjects on a whiteboard, but when you have to do it for your drone, it becomes fun.”

While relay racing, up to eight pilots each connect to a video channel that allows them to see the drone’s point of view through their goggles. If a ninth drone turns on, it automatically enters all eight video channels briefly, terminating the connection the pilots have with the camera on their drones.

A common problem among pilots is that they have to crash land their drones to disconnect from a channel. Because crash landing can damage expensive drones and injure observers, Hichwa decided he wanted to address the issue.

So he designed and produced his own circuit board: a switch that allows pilots to turn on and off their video transmitter—or VTX—without turning off their drones. This way, pilots don’t have to risk damaging their drones and relay races are less chaotic.

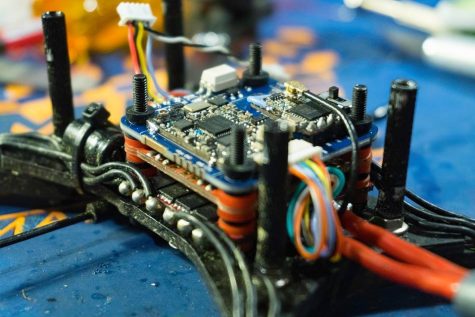

Pictured above is the blue circuit board, the OlaFPV VTX Assassin, designed by Hichwa. The circuit board allows drones to relay race and reduces the number of necessary wires. A few days after Hichwa released the product, he sent the part to prominent drone racers who posted photos like this one, which was taken by racer PhatKid.

Pilots will often yell “kill your VTX,” when their video connection is interrupted during a race, so Hichwa named the circuit board the “VTX assassin.”

Hichwa came up with the idea for the circuit board in June. He spent hours each day teaching himself how to design the product using an online program called Circuit Maker.

“I was unbelievably obsessed for the last month of school,” Hichwa said. “I remember just sitting there at lunch every day, hunched over my laptop, clicking buttons.”

Once Hichwa completed his design, he began reaching out to circuit board manufacturers in China. Over the summer, he communicated with his manufacturer every day via Skype. Because of the 11-hour time difference, he slept during the day and stayed up all night.

Hichwa said the process wasn’t easy, especially because of the language barrier and cultural divide. So to better understand China and ensure production went smoothly, Hichwa began researching the country’s history and culture. After watching “China Uncensored,” a YouTube series that incorporates news with satirical humor, his relationship with his manufacturer strengthened, he said.

Now, after months of designing his own drone technology and communicating with the manufacturer in China, Hichwa’s business is up and running. He received his first shipment of circuit boards Nov. 5 and now sells his product to his sponsors, drone parts companies and anyone who reaches out to him with a minimum order of 20 circuit boards. Hichwa’s company is called OlaFPV—OlaF for his name, and FPV for first person view, the vehicle category that drones fall into.

Olaf’s dad, Michael Hichwa, invested in his son’s company from the start because he wanted Olaf to learn basic business skills. Michael, who’s a computer programmer, said he’s proud of his son because he reminds him of his younger self.

“My parents were completely unable to help me with my computer programming, but they were supportive,” Michael said. “The same goes for me: he’s long surpassed any ability I have to provide him guidance or help. I’m very proud that he’s able to be self-sufficient.”

Liam Flanagan is a high school junior from Massachusetts who races drones and started his own business around the same time as Hichwa. They met through mutual friends. Over the summer, they traded advice: Hichwa taught Flanagan how to work with the software to design a circuit board, and Flanagan taught Hichwa how to manage the financial side of his business.

Flanagan admires his friend’s dedication, especially because Hichwa spent nearly 12 hours a day working on his design over the summer, he said.

“Once he gets an idea, he just starts going for it,” Flanagan said. “He becomes really focused on getting it done and he’s really excited about it the entire time.”

Now, Hichwa has slowed down the pace of his company because he can’t stay up until 4 a.m. on Skype during the school year. Although he’s taking a break from his business, he said his drone addiction isn’t fading because, for him, “drones are life.”

Hichwa isn’t sure he wants to pursue a career as a pro-drone racer. It can be a lot pressure to win races and the salary is inconsistent. But he wants to keep working with drones and continue developing products for his business as a career.

“I want OlaFPV to be my job for sure. I will do everything I can to make it my job,” Hichwa said. “I understand that it probably won’t pay for the Bethesda life, but that’s not really what I’m after anyway.”