It’s time to make a change in gymnastics culture

January 31, 2018

“I am here to face you, Larry, so you can see I’ve regained my strength, that I am no longer a victim, I am a survivor. I am no longer that little girl you met in Australia where you first began grooming and manipulating.”

Olympic gold medal-winning gymnast Aly Raisman testified on Jan. 19 as part of a victim statement to Larry Nassar, the Team USA, USA Gymnastics and Michigan State Gymnastics doctor who repeatedly molested and sexually abused her. Raisman now stands with over 160 women who have accused Nassar of the same behavior, including Olympic gold medalists Simone Biles, Gabby Douglas and McKayla Maroney.

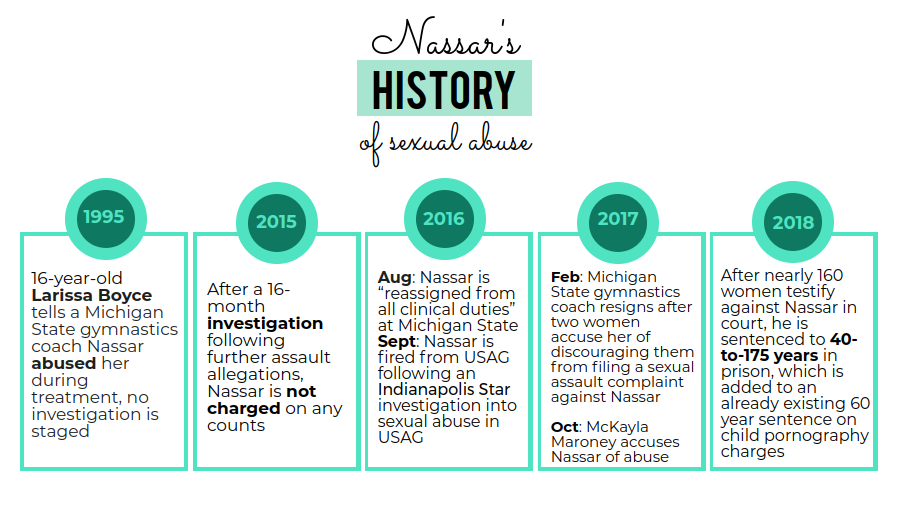

Nassar’s actions are disgusting and intolerable. What’s more astonishing, though, is how USAG has handled the situation—one that a they’ve evidently been aware of for years. Nassar was quietly dismissed from USAG in 2015 after the organization received multiple reports of abuse, yet they never released a statement indicating that his firing had anything to do with sexual assault. He continued to work for Michigan State Gymnastics until two gymnasts made public statements about his actions in September 2016, after which he was, again, quietly dismissed. Never brought to court, never charged.

Finally, Maroney, inspired by the #MeToo movement, posted on Twitter Oct. 17 that she had been abused by Nassar. He was arrested on several counts of child pornography and sexual assault and finally brought to trial. But this is far from enough to solve a widespread problem of both verbal and physical abuse directed towards gymnasts and other female athletes.

The culture of gymnastics is toxic from the top down. Even for very young athletes, the harsh environment makes it nearly impossible to speak out or even recognize how deeply twisted some coaches’ words and actions are. But this is the first time this corruption has been brought to the public’s attention; representatives from both USAG and the U.S. Olympic Committee repeatedly dismissed accusations against Nassar and continued to employ him after being fully aware of what he had done. Though Jan. 26 the entire USAG board announced their coming resignation, they still haven’t formally acknowledged the role they played in tolerating the abuse that so many of their top athletes endured. The most significant action the organization has taken is cutting ties with the Karolyi Ranch in Texas, the elite training center for the USAG National Team and many Olympic Team members, where countless women were assaulted by Nassar. Even so, the day USAG released this statement, there were still athletes practicing in the facility, Raisman testified.

The USAG sex abuse scandal, as it has been dubbed, makes it clear that it’s time to address a much greater problem within the culture of gymnastics and female sports. I’ve been involved with gymnastics since I could walk, and I competed for four years on a club team before switching to Whitman gymnastics my freshman year. I never made it to a particularly high level, but I spent at least 12 hours a week in a gym for four years of my life. At first, it was pure fun; it was an outlet for me to compete and learn. But as I progressed through the levels, the fun was overtaken by a verbally abusive atmosphere.

I understand that competitive sports require coaches to be tough on their athletes and push them to become stronger, but that intensity should never translate into body shaming, as it often does in the gymnastics world. As I got older, my male coach began telling me more and more often to “suck in that gut” or to “keep my big butt down” as we were doing pushups. I was even forced to repeat levels, not because I lacked the skills to progress, but because I “wasn’t strong enough,” which years later I realized was code for not having the proper gymnast body type—short and stick-thin. I even remember feeling jealous when one of my best friends developed an intense eating disorder, thinking that if I too had the motivation to starve myself I’d be a better gymnast. Of course, I never told anybody about the comments that my own coaches made about my body at the time; I was convinced that I was the problem. I was ashamed. I felt there was something wrong with me that justified my being treated this way. It got to the point where I was afraid to go to practice because I didn’t know how much more I could handle.

While my case is not extreme as many others, it is in no way unique. Almost every gymnast I know has an experience with one form of abuse or another that for so long we just accepted as the price of all those medals. The gymnastics culture teaches us that whatever our coaches say or do to us is in our best interest, whether that’s subtle comments that make us uncomfortable or sexual abuse.

Going forward, the gymnastics community should use the Nassar abuse case as an object for change at every level of the sport. Whether it’s body shaming or verbal and sexual abuse, this culture cannot and should not be tolerated any longer. No athlete should be afraid of what’s going to happen when they step into the gym, particularly female athletes facing abuse from male coaches. I sincerely hope that the gymnastics community will see this incident as a wake-up call and make a change in the way gymnasts are treated at all levels. USAG, it’s your move.