Obama-era campus sexual assault guidelines shouldn’t be discarded

November 22, 2017

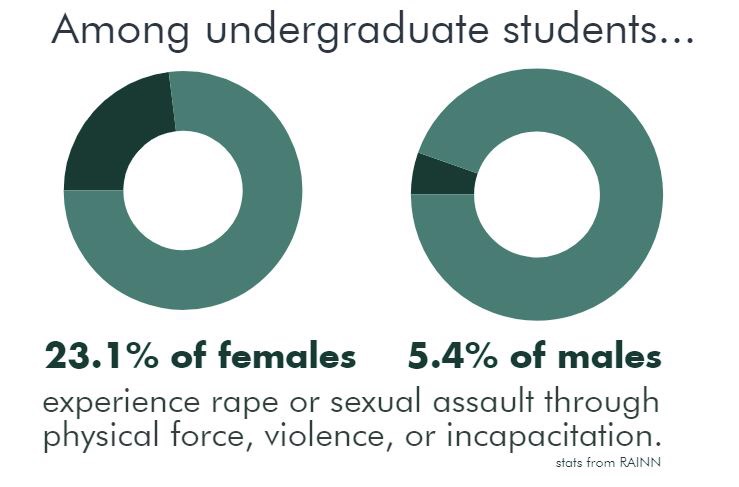

Sexual assault continues to be a serious problem on college campuses: about one in four female undergraduate students said they’ve experienced unwanted sexual contact conducted with force, incapacitation, coercion or lack of consent, according to a 2015 survey by the Association of American Universities. Although stories about campus sexual assault routinely run in the news, the federal government has yet to find an adequate response.

Rather than working towards a solution, Education Secretary Betsy DeVos has taken a step backward in protecting rights of sexual assault victims. In September, DeVos reversed an Obama-era campus sexual assault policy that created investigation procedures and student protections, claiming that the rules were unfair to accused students.

The Obama-era guidelines shouldn’t be discarded—without the policy in place, colleges won’t properly conduct their investigations and students are less likely to report misconduct.

The previous policy required that colleges treat sexual assault more seriously or risk losing federal funding. As a result, colleges nationwide introduced more robust campus support systems by allocating more resources and funding towards Title IX offices and counseling centers. Michael Hepburn (’17), a freshman at Gonzaga University, says that his campus has enough resources available to students that he hasn’t perceived fear of sexual assault.

Under DeVos’s new policy, colleges can abandon the previous standard of having a “preponderance of evidence” in their investigations, where more than 50 percent of evidence must show misconduct occurred. Now, a conviction requires “clear and convincing evidence,” which must show that it’s highly probable misconduct occurred. While this may seem like a minor semantic difference, it has significant practical implications for sexual assault cases that won’t be investigated because they don’t meet the specific criteria.

The previous guidelines also created clear procedures to ensure colleges conduct their investigations fairly and quickly. Colleges need these guidelines to clarify their responsibilities in handling these incidents. The recent standard changes make colleges uncertain about how to respond to sexual misconduct reports, Janet Napolitano, the president of the University of California system, said in a statement.

Additionally, the new standard for evidence discourages students from reporting sexual misconduct. The Obama-era policy created student protections by prohibiting a perpetrator from retaliating against a student who reports an assault.

The more stringent standard for evidence also favors the accused and casts inherent doubt on the victim’s experiences. Already, about 75 percent of victims don’t report incidents because they don’t think it’s serious enough or fear that people wouldn’t believe them, according to the AAU survey.

Since many of the cases that are reported come down to one student’s word against another’s, increasing the standard makes it nearly impossible to prove a case against an accused student and further discourages students from reporting sexual assault.

DeVos said she repealed the Obama-era guidelines to give colleges more freedom to conduct their investigations. But without the federal government pushing universities to address sexual assault, it’s unlikely universities will pay sufficient attention to this issue. Even with the previous guidelines, there were 223 colleges and universities under investigation by the Education Department’s Office for Civil Rights for violating Title IX, a Jan. 18 Washington Post article reported.

With the growing issue of sexual assault on college campuses today, students need more protection, not less. It’s time that the government stands up for sexual assault victims and prioritizes their rights.