Every summer, many graduating seniors embark on week-long, parent-free trips to nearby beaches. And every summer, memories — some incredible and some regrettable — are made.

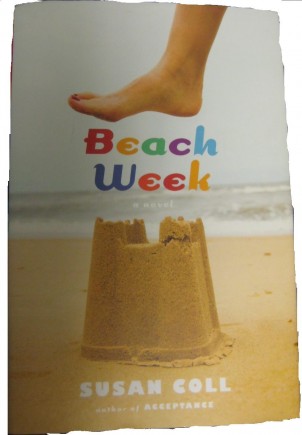

In her novel “Beach Week,” Whitman parent Susan Coll captures this teenage rite-of-passage. “Beach Week,” which goes on sale May 25, follows a girl who struggles to fit in at a new school, get along with her parents and attend beach week.

Main character Jordan Adler and her parents move from their humble home in Omaha, Neb., to a new house in Verona, a fictional suburb based on Bethesda. Adler’s initial desire to go to beach week forces both her parents and her to consider the consequences of spending several unsupervised days with friends, boys and alcohol.

Before sending their children to the beach, parents in Verona take many precautions to ensure that their children behave properly. For example, parents write a pledge that creates a buddy system, prohibits boys from sleeping over and forbids any alcohol in the house. The girls must also sign a legal document that makes them accountable for any damages to the house.

Susan’s daughter Emma Coll (’06) had to comply with these pledges and contracts when it was her turn to attend beach week.

“I think that parents often use litigation as an excuse to justify that they’re sending 17- and 18-year-olds away unsupervised for a week,” she says.

Though “Beach Week” pokes fun at Bethesda-type parents, Emma also felt that her mother explained a different perspective on beach week procedure.

“A lot of my friends felt she was spot-on,” Emma says. “She was able to make fun of these parents and portray it in a positive way.”

Though Coll’s characters face similar challenges to the ones Whitman parents face, she says these issues occur all around the country, not just in Bethesda.

Instead of chronicling the dangers of Beach Week, Coll satirizes parents who vainly try to control their teens.

“All the meetings, all the time, all the money and hand-wringing that goes into planning goes out the window pretty much within the first day of beach week,” Coll explains. “Parents think they can control teen behavior by making them sign pledges and liability waivers and making all these promises.”

Emma says that she and her housemates found ways around their own parents’ no-alcohol contract.

“One girl’s mom drove her up to the house, and when she got here we put all the beer in the bathroom and had someone pretend to take a shower,” she says. “There are ways around getting caught.”

Though some may interpret the novel as social commentary, Coll says she’s not trying to deliver a moral message to readers.

“If anything, I was satirizing a certain kind of parenting,” Coll says. “You hear everyone up in arms about kids in this generation, but it’s the same as my generation.”