As a public high school, we turn to local government for our curriculum and models of instruction. But colleges, with their more autonomous and loosely-prescribed curricula, are looked to as the leaders of the educational world. That also makes them our guinea pigs for any academic endeavors—and recently, we’ve been learning quite a lot from their blunders.

“Trigger warning” is the newest buzzword of our generation, the talk of publications like the New York Times, The Washington Post, The Guardian and The Atlantic. Used to label traumatic content like graphic violence, sexual assault or other abusive behavior, these prefatory words have induced anxiety for instructors and students worried they may spout something offensive or scarring to nearby listeners. Everyone from professors to lawyers to psychologists has offered insight and opinions through media coverage of the movement, but a realistic middle ground is yet to be reached between the conflicting views.

This September, The Atlantic published “The Coddling of the American Mind,” a collaboration by two guest writers that immediately went viral. The article challenged a growing demand for college campuses to be safe spaces, saying what many professors and administrators had been thinking. Co-writers Greg Lukianoff and Jonathan Haidt, a constitutional lawyer and social psychologist, discuss censorship in the college classroom and why it’s undermining the intellectual prowess and emotional resiliency of students.

When the article was published, professors all over the country reached out to Lukianoff to thank him for standing up against what he called the “vindictive protectiveness” students enforce in the name of other students’ wellbeing, he said in an interview with The Atlantic’s Editor in Chief James Bennet. The authors explained that students are not simply watching each other’s back, but approaching people with malevolent intent, oftentimes making the assumption that those around them are ignorant.

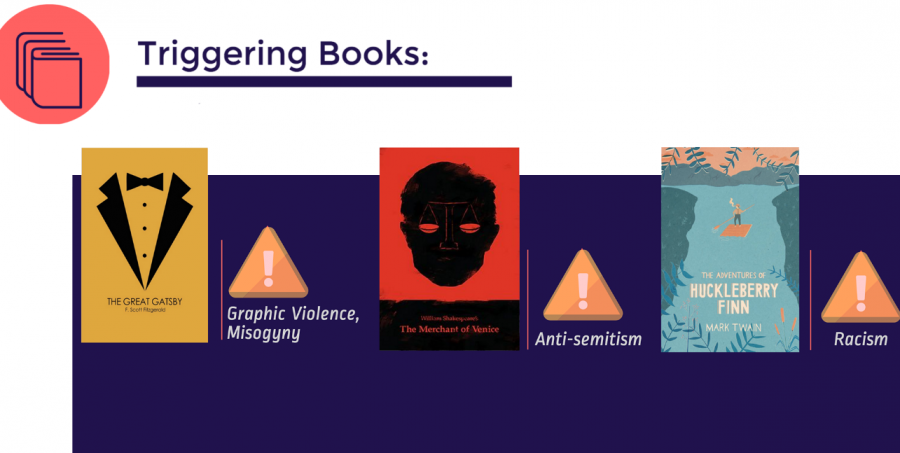

The authors also include extreme examples of what are becoming more and more common in the classroom. A Harvard law professor was asked to stop teaching the legalities of rape, and in one case the article cited, a professor was to refrain from using the word “violate” for fear of triggering reactions from sexual assault victims. “The Great Gatsby” and Shakespeare’s “The Merchant of Venice” have also been targeted as needing trigger warnings for misogyny and anti-Semitism, respectively. Some students even use this as rationale for opting out of reading class material entirely.

This misguided safeguarding isn’t simply the political correctness of the ’80s and ’90s to protect minorities from hate crimes and diversify classroom material. It’s creating a culture where civil dialogues are absent. Taking offense isn’t simply a mundane tribulation but a platform for, as The Atlantic’s guest writers described it, maintaining the “fragility of the collegiate psyche.” According to the article, trigger warnings lead to a colored view of reality, propagating an oversensitivity to life’s unsympathetic moments—something especially dangerous as those affected join the adult world.

On the other side of the continuum, Kate Manne’s article “Why I Use Trigger Warnings,” appeared in The New York Times, also this September, clarifying the underlying assumption that many critics fail to address: the rationale behind the initial conception of trigger warnings.

Originating during World War I, trigger warnings were introduced to shield PTSD victims from horrific, debilitating flashbacks. Manne explained that any reactions triggered by certain academic content isn’t something to be rationally processed; these reactions are crippling. So to argue that reactions from traumatic content should be worked through therapeutically is to misunderstand the problem. However, that’s not to say that the vast majority of students fall within this category of emotional fragility.

According to her article, trigger warnings are simply an unavoidable precaution because, statistically, there is a small yet definitive number of abuse victims in any given class who could be prone to these reactions. She doesn’t cite any data with this claim, but if it’s true it should be cause for concern. We should be asking why there is such a high number of rape and abuse victims in our student bodies to begin with.

If we as a country really have such a high percentage of abuse victims in our classrooms, maybe trigger warnings are treating the symptoms and not the problem.

This is where the matter begins to get fuzzy. While trigger warnings have commandeered recent classroom instruction, they are rooted in reason—but the numbers are much smaller than originally conceived. Only five percent of teens ages 13 to 18 met the criteria for PTSD when surveyed on a nationally representative scale, according to the National Center for PTSD. From a moral perspective, appealing to that five percent by introducing potentially triggering classroom material with an unintrusive, easily ignorable one-liner and avoiding any disturbing reactions seems justifiable.

But to compromise the classroom’s intellectual material contradicts the purpose of an education: attempting to understand offensive, misunderstood material in the hopes of deriving a higher truth.

Our country is undoubtedly in need of radical social change. Institutionalized racism is just as real as the countless sexual assault victims we hear about on the news, and they’re just as real as the transgender and genderqueer voices we don’t hear about on the news. But shying away from valuable yet triggering content and policing what we discuss isn’t going to create a brighter future. Let us acknowledge our faults as a society and work toward eliminating them instead of pretending they were never here to begin with.