Down the street from Franklin Park in Northwest Washington D.C., a large red brick building opens its doors to the public. Through the miniature side garden, a mixed-media aluminum installation marks the entrance of Planet Word, an interactive museum focused on world languages.

Planet Word is one of the few museums in the country dedicated to words and language. The space inspires a greater love of language and education surrounding it. The museum is completely free of charge, being owned and operated as a non-profit funded by donors and grants. Opened at the height of the pandemic, the museum has worked to create a new perspective on words and reading. Ann Friedman, a retired teacher, developed the concept as a response to the illiteracy rate in the country, now at 32 million.

Many of the program advisors are writers and professors, passionate people interested in developing a space like Planet Word. Museum Director of Education, Caitlin Miller at the museum, came to the staff with a background in research and non-profit organizations. Eager to create such a unique space, Miller joined the team for the museum’s opening.

“Planet Word is a place and an experience that believes that everyone has language, a right to language and a right to change it so that it serves them,” Miller said. “You see that represented in the galleries and in the experiences at Planet Word.”

Walking deeper into the museum, visitors see the galleries and experiences that Miller highlighted. Brightly colored visuals tell about the history of words, how they’re made, and their future. Language constantly adapts; the museum dives into how words are created and how they will continue to change.

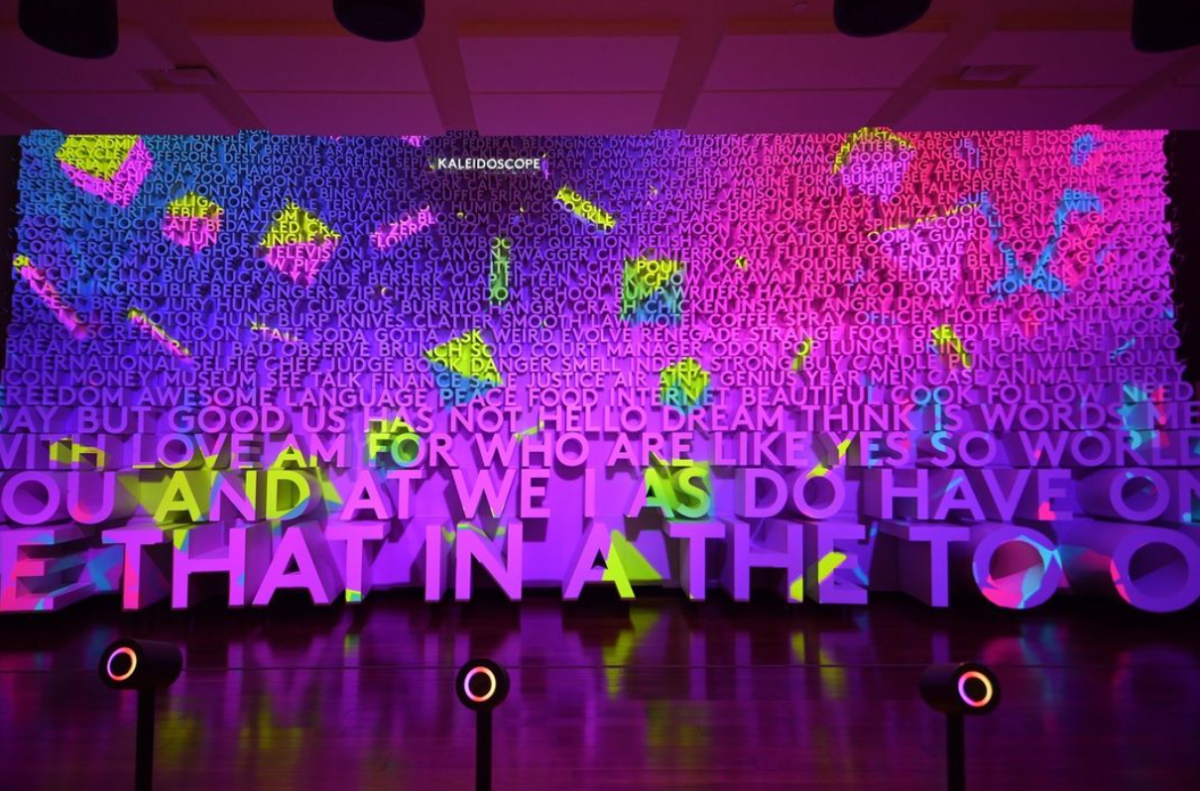

Planet Word’s “Word Wall” evokes reflection on dialects from around the globe while inspiring discourse on cultural norms and differences. The exhibition spotlights words from the English language that light up during a spoken presentation about different features of the words, including their origins, purposes and current usage.

“The Speaking Willow,” a sculpture created by Mexican artist Rafael Lozano-Hemmer, sings to museum passersby with recordings of different languages. Emerging from the tree’s branches, speaking patterns and inflections of different syllables pour out of the speakers, displaying the beauty of spoken words and preparing visitors for the museum experience. The piece references a natural element of our world, connecting spoken language to the world outside of the museum. Visitors both entering and exiting the museum see the sculpture, causing a different reflection each time.

The museum houses permanent exhibitions and cycles through seasonal exhibitions, one of which is “Word World.” Word World is a small, isolated room set in complete darkness, where natural and urban scenery is projected onto the walls. Sat on a low shelf mounted on the wall, paint brushes are meant to be dipped into empty cans labeled with metaphorical adjectives like “parched,” — which means having been dried out, or “surreal,”— which means dreamlike or bizarre. The paintbrushes use sensors to take a chosen word and carry it onto the wall. Aftera visitor makes contact, the walls seem to move around, shifting and transporting the visitor into the world they’ve created. If a child dips their paintbrush into the “parched” category, for example, the branches of the trees begin to go colorless, and the water fountain stops streaming. The features of the scene blend and shift in lines of movement, almost as if Van Gogh had painted them. People of all ages walk through the space, including Raymond Gotha, a high schooler who has visited the museum twice. According to Gotha, Planet Word tore down his ideas of how museums work.

“Most museums just show something and information about it,” he said. “This museum has a lot of things to do and interact with; it’s more fun.”

The space’s main attraction is a massive globe of small dots that light up in hues of blue and green, signifying land and water. The globe fills up the third floor’s main room as visitors try to locate their home country and places they’ve visited. Around the room are tablets with recordings of people from various cultures speaking about and in their languages. When visitors interact with the tablets, the recordings ask them to pronounce words in other languages. The globe in the center of the room visualizes specific societies’ history and culture through LED imagery.

“We know the three different forms of learning,” said Jalen Thompson, a Planet Word staff member. “There are audio learners, visual learners and kinesthetic learners. This museum hits all three in one way, shape or form.”

The museum’s approach to teaching attracts a wide range of ages. No child is too young to enjoy the area, and no adult is too old— whether drawn toward the karaoke room or the animated library.

The museum’s content includes a wide range of art representing different stories. The museum travels through the long history of language, moving through critical moments in the origin and evolution of contemporary linguistics. Audiences learn about the factors that impact the creation of new dialects; teenage girls, for example, have been some of the biggest language creators.

“We represent many different types of people that you may or may not know about,” said Thompson. “This is a really great place to deepen your learning of anything. I think that’s very special.”

The museum exposes students to different parts of language and culture. Interactive education spaces like Planet Word provide beautiful connections between what schools teach and their real-world applications.

Leila Hoskins is a high school student who chose to explore Planet Word when she visited D.C.

“Where I’m from, we don’t have a lot of museums or places like this,” Hoskins said. “So it’s really cool to come here and […] be able to interact with it. I think that really draws people in.”

Planet Word’s importance is far-reaching. The museum’s goals and principles continue to develop and inspire people of all ages and backgrounds.

“Literacy is the foundation of a strong democracy,” Director of Education Caitlin Miller continued. “We think that reading and processing complex information closely is a crucial skill for every person and citizen to find their way in the world. I think that’s absolutely true for young people on the cusp of entering adulthood.”