The lasting impact of the Armenian Genocide

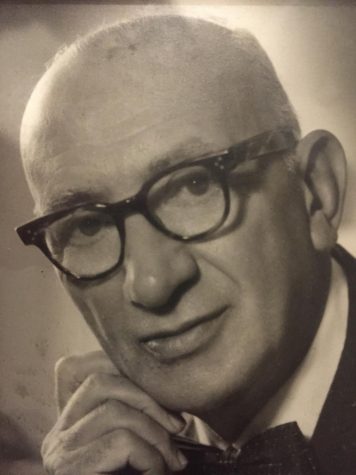

A photo of my great-grandparents Krikor and Astrid Papasian. Krikor married Astrid in Belgium after leaving behind his friends and family in order to survive the Armenian Genocide.

February 6, 2020

For most of my life, I saw my Armenian background as a trivial part of my family history. My family and I often joked about how our very white family technically originated from Asia, and we loosely connected ourselves to celebrities with Armenian origins like the Kardashians, Cher and Food Network Chef Geoffrey Zacharian. But not until recently did I take time to consider the implications of my heritage.

Last November, Senator Lindsey Graham (SC-R) blocked a resolution that would have had the U.S. officially recognize the Armenian Genocide. This marked the third time Republican senators blocked the resolution under direction from the White House. Their motive was clear: to appease the president of Turkey, Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, a staunch denier of the Armenian Genocide. How could our government refuse to recognize the systematic slaughter of an entire people? This blatant denial inspired me to research my heritage. I talked to my dad and my great uncle, I skimmed a few Wikipedia articles and I read the stories of survivors.

The Armenian Genocide took place from 1915-1917 when the Ottoman Empire killed an estimated 1.5 million Armenians. There are 29 influential countries that recognize the genocide, but Turkey still disputes the death toll and argues that there were deaths on both sides. Despite virtually no evidence to support Turkey’sclaims, the U.S. government continues to yield to the Turkish government on this issue. Thankfully, Senator Bob Menendez (NJ-D) led the Senate to overcome objections from Republicans to pass a resolution Dec. 15 that recognizes the Armenian Genoicde. The passing of the resolution is a step forward, but it took far too long for the U.S. to recognize and legitimize the deaths of 1.5 million people.

While legislators argued over whether or not it would be strategic to recognize this genocide, I did some research to find out what actually happened to my ancestors. I learned that the Ottoman Empire would force men into manual labor and starve them so they would die after a cruel, short, hard life. Ottoman forces burned Armenian towns to the ground. The Ottomans would drown Armenian women and children in the Black Sea, and the Ottoman government would hire physicians to poison Armenian civilians.

My great-grandfather, Krikor Papasian, was living in Constantinople at the time. He was forced to leave his family — his parents and his brother — because the Turkish government would have killed him if he stayed. Krikor then hitchhiked through Europe, eventually making his way to the United States, where he worked as a glass blower. He soon opened a jewelry business in New York, and he helped his surviving family members immigrate to the U.S. He was lucky, and his brave decision to escape is one of the reasons why I’m here today.

But others weren’t as lucky; many of my great-grandfather’s friends and family members were killed, brutally and needlessly. Our government had the opportunity to legitimize these deaths and hold the Turkish government responsible. Instead, it continuously failed to recognize that these people were murdered.

U.S. policymakers consistently ignored the tragedies inflicted upon my family. By only considering the U.S.’ strategic interests, they’ve rejected morality and demonstrated that they don’t care about the turmoil that my family and millions of other people experienced. It took 100 years for our government to react to this — that’s unacceptable. Having learned what my great-grandfather and his family went through, I find it unbearable to watch policymakers bend the knee to hostile foreign powers and forget about justice.

reuben stoll • Mar 3, 2020 at 10:11 am

TO whoever said Obama was a coward I don’t think you understand how courageous you have to be to be the FIRST African American president. There is no partisan opinion in this piece I really think you should read the article again and realize what you just said. Again Jack this is a wonderful article and I am sorry that these ignorant people fail to see the lasting impact this had.

OBAMA also failed the Armenian People • Mar 3, 2020 at 8:33 am

Author fails to note that Obama also caved to Erdogan’s demands like the coward that he was. Shameful that author has a partisan twist on a genocide.

Katerina Dorian • Feb 9, 2020 at 6:34 pm

Hi, I am a fellow Armenian student and recent graduate of Walt Whitman High School. Anyone who denies the genocide is unfortunately allowing themselves to be subjected to the same brainwashing Nazi Germany and Stalinist Russia did in respect to their mass murders of certain ethnic/religious groups in hard labor/death camps. Jack, I commend you for writing this article and raising awareness about a topic that has consistently been swept under the rug by many powerful political leaders. My great grandfather came to this country as a child with his sister after the ENTIRE REST OF HIS FAMILY was exterminated by Ottomans. My great grandmother was forced on a death march from Turkey into Syria where she and her mother repeatedly had to fend off Ottoman soldiers that were trying to rape them. How can I verify this? My father taped his grandmother telling her story. In other words, we have absolute irrefutable first hand evidence.

The problem that I do have with this article is that it unfortunately takes a very sensitive issue and twists it to fit a partisan narrative. Why are you characterizing “all Republicans” as against recognizing the genocide just based off of the negative vote of one, Lindsey Graham? Is it because of some sort of preconceived notion that all Republicans are racist and xenophobic? You failed to include the fact that TED CRUZ coauthored the same BIPARTISAN piece of legislation with Bob Menendez that you mentioned. As a proud Republican and a proud Armenian, this is an extreme disappointment. Of course some Republican officials ignore the genocide due to to the extreme importance of Turkey’s geopolitical alliance. Has Trump done that in the past? Absolutely. But so did Obama who promised on his campaign trail to recognize the massacre and never once mentioned it during repeated diplomatic trips to Turkey. Please recognize that there is ignorance on both sides of the aisle and as Armenians, we should all work together to ensure that this slaughter is as talked about as the Holocaust now is in America.

chloe lesser • Feb 8, 2020 at 5:47 pm

Anonymous Whitman Parent,

there’s no “both sides” to whether or not a genocide happened. the “other side” of jack’s argument is denying facts and perpetuating ignorance.

Thanks!

Finn Martin • Feb 7, 2020 at 5:53 pm

Dear Anonymous Whitman Parent, To criticize a high school reporting on a GENOCIDE as “not ethically right” is not ethically right. Crazy that you would think that this literal, irrefutable GENOCIDE has “opposing viewpoints.” I think it’s appalling that some people like you believe lies like GENOCIDE DENIAL in spite of literal piles of evidence that say it happened. It’s disappointing that people in the Whitman community, like you, would fail to see this evident truth and would even go so far as to publicly denounce truthful reporting to cover your delusional beliefs. I prefer to remain known due to the fact that I’m not hiding behind anonymity to publicize my opinions when it comes to this “controversial topic.” Thank you.

Anonymous Whitman Parent • Feb 6, 2020 at 9:19 pm

Dear Black and White,

To publish such a controversial article without providing readers with the points of view of both sides is not ethically right. You also have not provided any verified sources for your claims, which, as you know, is the basis of journalistic writing. I think it is appalling that your sources consist only of “a couple Wikipedia articles” and “some research.” This debate carries much weight and it is disappointing that Whitman’s journal would publish this article without giving opposing viewpoints and sources.

I prefer to remain anonymous due to the controversy that encircles this topic.

Thank you.