Modernize sex education: stop preaching abstinence

May 9, 2018

Don’t have sex. If you do, you will certainly contract at least one STD or STI and end up pregnant and struggling at 16. The only solution is to practice abstinence—or so the county’s health curriculum might have you believe.

In Montgomery County, all high school students are required to take one semester of health before graduating. After a quarter of health in 8th grade at Pyle, high school health is the second and final time students are taught about methods of contraception. And, of course, teachers preach abstinence again. In middle school, 6th and 7th grade health curriculums only focus on healthy relationships, and 8th grade splits time between common contraceptives and abstinence, county health education supervisor Cara Grant said. MCPS’ health curriculum should increase class time devoted to contraceptive education and restructure the unit to cover the most common forms more to ensure students have more resources to practice safe sex and to decrease the probability of teenage pregnancy or contracting an STD.

Regardless of any school health curriculum, teenagers will have sex. In the U.S., 46 percent of all high school age students and 62 percent of high school seniors have had sexual intercourse, according to the CDC. The Pew Research Center found that the average age for initiating sexual activity has remained around 17 or 18 since the early 1990s. Six percent of all U.S. high school students had sex before age 13. For many, high school brings more serious relationships and the feeling of having the requisite maturity for sexual activity.

For this reason, Kathrin Stanger-Hall and David Hall of the University of Georgia found in a study of 48 states that abstinence-only education is ineffective in preventing teenage pregnancy and may actually contribute to the high teenage pregnancy rates across American socioeconomic classes. While MCPS’ current system is an abstinence-based program and includes some other contraceptive methods, abstinence-focused programs have also been found to fail to delay the age of sexual activity or change other risky sexual behaviors, Laura Lindberg of the Journal of Adolescent Health concluded.

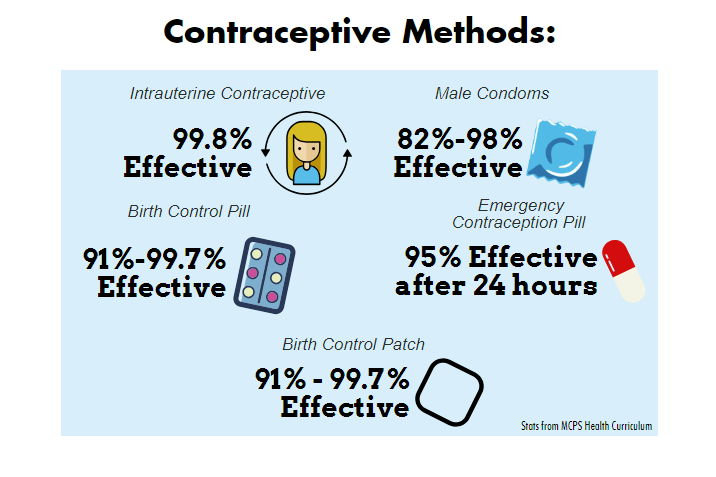

If the health curriculum can’t prevent students from having sex, it should at least teach safe methods. But when half of class time is spent on abstinence, that leaves only half of class time to cover all the various forms of contraceptives, meaning each is only discussed for a fraction of a day. Most students are familiar with the most common forms of contraceptives: condoms and the birth control pill, though not necessarily through health class. The county needs to dedicate more time to other, more common, options: emergency contraception pills, such as Plan B, IUDs, birth control injections and patches, female condoms, implants and diaphragms, to name a few. Advocates for Youth, an organization that advocates for a more positive and realistic approach to adolescent sexual health, found that up to thirty-nine percent of all sexually active U.S. high school students didn’t use a condom during their last period of intercourse. Twenty-two percent of sexually active females age 15 to 19 have used emergency contraception, such as Plan B, a study from the National Center for Health Statistics concluded. In high schools, contraceptive methods besides abstinence and condoms are all covered in equal depth; tubal ligation is just as common a topic as Plan B. It is up to schools to shift focus and devote class time to the most practical and common methods in order to make safe sex more likely.

Opponents argue that a curriculum not centered around abstinence normalizes and even risks encouraging teenage sexual activity. The issue with this mindset is that teens already think about sexual activities and are aware of what sex is through friendships and media portrayal of sexual relationships. And sex education doesn’t encourage risky sexual activity, Joseph Sabia of the Association for Public Policy Analysis and Management found. What the curriculum can change, however, is the student’s precautionary and preventionary actions.

It’s up to the county to help educate students on how to be safe. Abstinence education fails to do that.