Stop tracking demonstrated interest, make need-blind admissions real

April 17, 2018

In the coming weeks and throughout the summer, nearly every Whitman junior will visit colleges, traveling across the country and even internationally to meet with admissions officers and sit through information sessions. It’s college season, and touring is a way to show interest in a school—a factor many colleges unfortunately take into account when deciding admissions, creating implicit bias against low-income students.

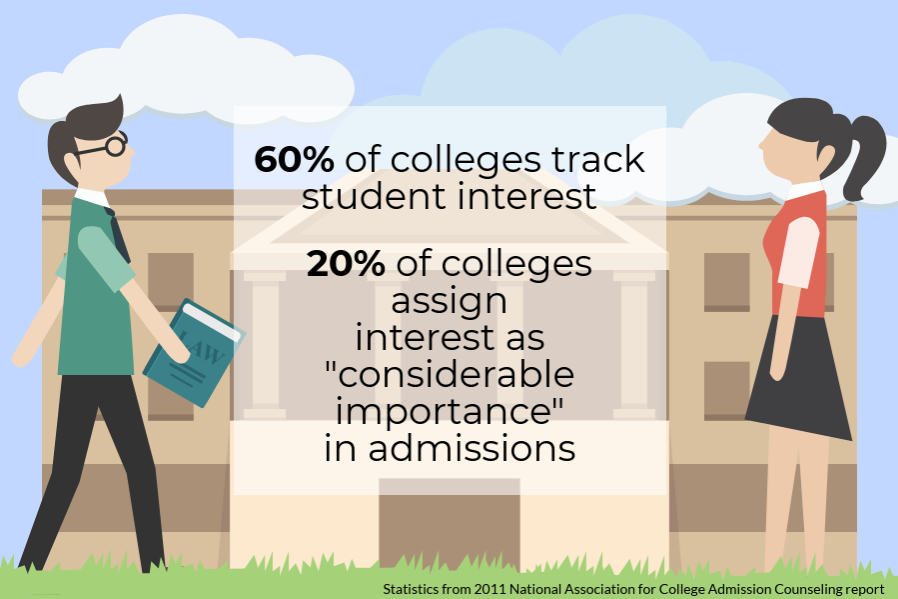

Such visits fall under the umbrella of “demonstrated interest,” which is the degree to which an applicant indicates to a school that they are likely to attend if admitted. About 60 percent of colleges track students’ interest, and about 20 percent of colleges assign it at least “considerable importance” as a factor in admissions, a 2011 National Association for College Admission Counseling report found.

Students can demonstrate interest with as much as a campus visit or as little as emailing an admissions representative. The strongest form of demonstrated interest is applying early decision, a type of application that requires the applicant to attend the college if admitted.

Colleges and universities should stop factoring demonstrated interest into admissions in order to combat wealth and achievement gaps and level the playing field for all applicants, regardless of background.

Colleges tend to favor students who show heavy interest because rankings, such as the influential US News and World Report, use factors like yield to calculate a school’s spot on the list. Having both off- and on-campus contact—like emailing an admissions officer and taking a tour of the campus—increases the probability of acceptance by up to 24 percent, a study authored by Lehigh University economics professor James Dearden revealed. The study also found that even just off-campus contact made a difference, increasing a student’s chance of admission by 13 percent.

Problems with demonstrated interest, however, arise first with lower income families. Wealthier families are able to spend thousands of dollars and take time off work or school to go on expensive tours across the country. Applicants from more affluent backgrounds are then able to visit more schools and attend more meetings, while for lower-income families, such expressions of interest are often too expensive or time-consuming. Moreover, first-generation and low-income students aren’t always aware that demonstrated interest is a factor in admissions and can lack the resources to know which colleges track it. Sending an email to an admissions representative isn’t always the hard part; it’s also knowing when and how to write it—or even that it’s necessary at all.

The ED application option also makes it harder to create a fair playing field for applicants by disadvantaging those who wish to compare financial aid offers, a 2016 Washington Post article explains. Early-admitted students who have applied ED are bound to a school whether or not their financial needs are met, which can dissuade lower-income students from applying early. This is especially harmful considering some schools draw up to 40 percent of a class from ED and acceptance rates for ED are also significantly higher than regular decision, though this disparity could be partially explained by the larger number of applicants in the regular pool.

Admittedly, it seems fair to allow students more interested in a school an edge in admissions; affluent students, however, frequently have the resources to indicate interest even if they do not plan to attend a college. Additionally, it is true that interest isn’t the only element of an application—in fact, of the many aspects already considered in the admission of a given class, financial diversity is a factor. Overall, though, it’s more important to level the playing field than to lend a hand to those who already love a school or those who can pay. Otherwise, the supposed “meritocracy” of college admissions exists in name only.

It’s time to stop building barriers for low-income students and start offering equal opportunities to applicants. Students shouldn’t have to check off boxes to demonstrate their interest in an effort to play the strategic game of college admissions; the only way to make need-blind admissions a reality is to move toward disregarding financial status—both overt and implicit.