Despite 50 years of progress, tensions from 1968 remain

March 9, 2018

1968 saw the first-ever national anthem protest, the assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and growing unrest towards U.S. involvement in the Vietnam War. 2018 has seen the continuation of some of these tensions: athletes are kneeling during the national anthem, the Black Lives Matter movement is growing and people are protesting the Trump administration.

Despite a 50-year difference, both 1968 and 2018 have brought deep racial tensions and new waves of political activism to the country. These striking similarities have prompted a belief in many, both in the Whitman community and across the country, that the country’s racial divide is perhaps larger now than 50 years ago.

A Racial Divide

In early 1968, Whitman’s gym housed a concert with performances from the Marvelettes, Wilson Pickett and Martha and the Vandellas. Groups of African Americans from D.C. unexpectedly arrived at the event, hoping to catch a glimpse of the performers. Many white attendees and homeowners were aghast at their arrival, so much so that some even called the police, Kenny Appelbaum (‘69) said.

Like today, Whitman was predominantly white in 1968: fewer than 20 black students attended the school, which had more than 1,000 students. Though white students far outnumbered minorities, 13 alumni of both races say they believe racism was nearly nonexistent among the student body.

“I never had an incident where racial insults or disrespectful acts or language were made towards me, nor can I recall any of the other African Americans in the school having any negative experiences,” Philomena Green Morsell (‘69), who was one of three black students in her graduating class, said.

But outside of the school, discrimination was the norm: African Americans and Jews weren’t allowed to live in certain neighborhoods, housing contracts prohibited whites from selling their homes to those of other races and parents discouraged their children from socializing with minorities.

“It was understood that we were better and they were worse,” Victoria Crawford (‘69) said. “It was very clear that it wasn’t okay to be black and to date someone of a different race.”

These tensions escalated after Dr. King’s assassination in April 1968. Protesters torched D.C. businesses and raided shops, much like the 2015 riots in Baltimore following the death of Freddie Gray. Alumni recall seeing the flames from their homes, and police prohibited Maryland residents from leaving the state during the chaos. King’s assassination shocked the country, filling Whitman with a sense of horror among staff and students the following day.

Martin Luther King gave us a voice. He was fighting in a peaceful way for our rights as American citizens. He was our voice, and that voice was silenced by hatred. That unwarranted hatred was and still is the cause of our anger.

— Philomena Green Morsell (‘69)It started with disbelief, next sadness and then anger,” Morsell said of the assassination. “Martin Luther King gave us a voice. He was fighting in a peaceful way for our rights as American citizens. He was our voice, and that voice was silenced by hatred. That unwarranted hatred was and still is the cause of our anger.”

For Rep. John Lewis (D-GA), a colleague of King’s who walked with him in his historic march from Selma to Montgomery, AL, the assassination was shocking and painful. Though society has changed significantly since the assassination, Lewis sees a parallel between now and then.

“Racial tensions in 1968 weren’t much different from the racial tension of 2018,” Lewis said.

This issue was evident in the Whitman community this year when freshman Brian Ellis shared in a schoolwide assembly that he was called the N-word by his peers on multiple occasions. Ellis said he also faced racial bias from teachers and students at Pyle and added that he “never experienced this type of racial hate” when he lived in places like Chicago and Memphis. Despite these issues, not all minority students have shared Ellis’s negative experiences; some feel Whitman is an inclusive community, like in 1968.

“For kids that come from a minority background, everybody in the school is very welcoming towards us,” junior Nick Boone said.

Activism in the Community

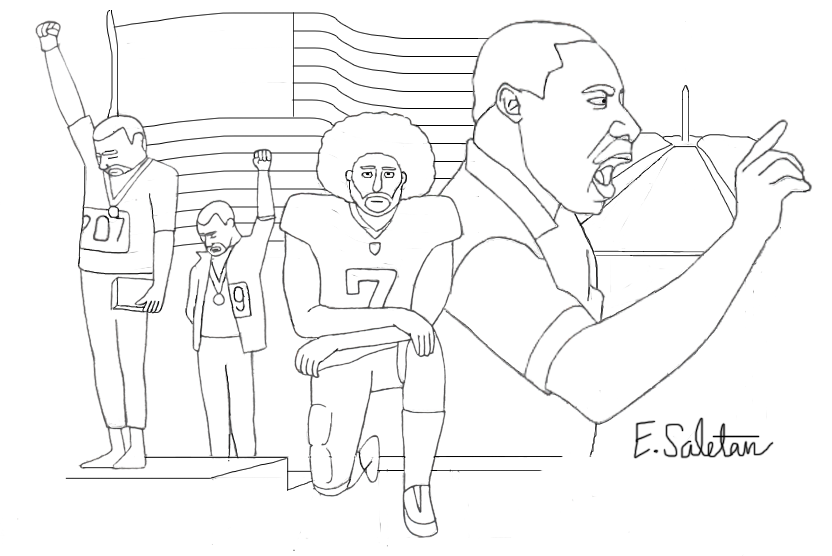

As the Star-Spangled Banner played during the 1968 Summer Olympics in Mexico City, the world watched as American track and field stars Tommie Smith and John Carlos raised their fists in the air, protesting the prevalent discrimination against blacks in America. The athletes received mixed reactions to their protest, including death threats.

Similar anthem protests are common today, as athletes across the country, like former 49ers quarterback Colin Kaepernick and Redskins wide receiver Jamison Crowder, knelt during the anthem to protest racial inequality and police brutality. The response has been similar to 1968; Americans are still divided as to whether the protests are an example of freedom of speech or a sign of disrespect towards the armed forces.

The protests became local last fall, when many Montgomery County athletes, including Boone, a football player, knelt during the anthem before sporting events.

I wanted to kneel because there are a lot of racial problems, and I felt doing it at Whitman made it show that we’re all one.

— junior Nick Boone“I wanted to kneel because there are a lot of racial problems, and I felt doing it at Whitman made it show that we’re all one,” Boone said.

Student activism in 1968 largely centered around the country’s involvement in the Vietnam War, as many were at risk of being drafted. Back then, students often faced opposition from their administrators; today administrators strive to be more supportive. Still, political groups are restricted from spreading their full message: administrators recently prohibited the Vikes for Action club from selling “Vikes Stand with Planned Parenthood” t-shirts on school grounds.

“We always have to be careful that when we present a point of view, we have to present another,” principal Alan Goodwin said.

Looking Ahead

Over the last 50 years, the country has made many steps toward racial equality. Barack Obama’s election as the first African-American president and legislation to decrease housing discrimination, among other efforts, have helped ignite progress in the fight against racial tensions in the U.S. Still, many of the issues the country faced in 1968 remain startlingly prevalent.

Recently, the country has witnessed an increased unity behind political activism, generating mass forms of protest, including the Women’s Marches. Just like in 1968, with the increase in tensions comes an increase in activism, and the activism doesn’t appear to be slowing down anytime soon.

“The times that we’re in right now where we demonize other groups doesn’t serve any of us, so I think there’s a parallel,” Crawford said. “Back then, the division was deeper and quieter. Now it’s more visible because we have the media, TV and activism.”

Leland P Gamson • Mar 16, 2018 at 1:50 am

Since 1981 I have resided in Marion, Indiana, a rust belt factory town that is Trump country. We live in an old neighborhood a few blocks from downtown. Within a two block area about thirty percent of our neighbors are Black and there are three interracial families. I see Black, Hispanic and white youths walking together and playing at our Y together daily. In nearby “redneck”, Gas City,the president of the Chamber of Commerce is a Black women. Recently a vendor peddling Klan ornaments was escorted out of a city festival.

Anyone who thinks that race relations are the same in 2018 as they were in 1968 does not live where I live.

Victoria Crawford • Mar 15, 2018 at 1:35 pm

Thank you Eric for this well written and timely piece.

I’m thinking about what keeps racism alive and sense that it some ways it’s the hidden nature of what is passed down through generations that is unquestioned. It’s those undercurrents within families and communities that are allowed to fester. I do think we have made progress over these 50 years but I would like to have more open and courageous conversations on this subject where there was an opportunity for both powerful questions, respectful listening and creative problem-solving. I remember seeing something on PBS years ago where this type of discussion happened with a very diverse group and was well facilitated by a strong leader. What stayed with me was how much I learned from being able to listen to the collective wisdom on both sides…

kirk huang • Mar 15, 2018 at 10:47 am

Interesting article from a pivotal time in our country’s history. I would love a followup article on the climate that exists today regarding these same issues and perhaps how the Trump era has impacted the attitudes and behaviors of students

Kudos for the effort and best regards

Paul Freedman • Mar 14, 2018 at 11:00 pm

The very lack of diversity precluded as far as I remember the very hostility Kenny remembers, Jews might have been stuck in Kenwood Park and Landon Woods or Banackburn instead of Kenwood down the road (maybe)–oy and vey!. The flames of the D.C. riots (this was a local Montgomery County school) could be seen from the Zenith TV in the den, not from out the window. I don’t think there was a police blockade around the Maryland suburbs. The major tension this senior citizen recalls was between the freaks and the greasers and some half-articulated hard feelings when the Christian Fellowship fronted a student government slate. Things remain the same but they change too.

Jo Schneiderman • Mar 15, 2018 at 6:40 pm

I also remember Whitman in 1968 very much the way Paul Freeman remembers it. Jewish/Christian segregation as well as black/white segregation. And I definitely remember the conflict between the freaks and the greasers. We couldn’t see the flames from the Whitman area, but we felt the effects. The more things change……

Lisa Howorth • Mar 14, 2018 at 6:09 pm

Nice article, Eric. I was glad to help with it. I’ve been thinking today about how proud I am of WWHS– I read the Wapo article on the gun protests, and was glad to see so many WW students participated. Activism has always been alive and well at Whitman, and even though we were such a privileged, white student body, many students cared about racial issues. (I disagree with my old friend and ’69 classmate Philomena that there wasn’t bias–I knew some racist kids–but I’m very glad she never personally experienced that). It’s interesting to me that Brian Ellis commented on the racism he encountered at Pyle/Whitman, which he hadn’t experienced in Memphis, a city close to me here in Mississippi.

Although the deep south has a deservedly terrible reputation on civil rights and a very dark history, because black and white southerners here live in close proximity with every-day interaction (unlike Bethesda), they’ve had to learn a certain amount of cultural understanding and acceptance in a very real way, especially since the Sixties. Which is not to say there isn’t still a lot of work to be done.

Philomena Green Morsell • Mar 15, 2018 at 7:06 pm

I want to commend Mr. Neugeboren on this timely article and to thank him for the opportunity to contribute my experiences at Whitman. Unfortunately, I feel the need to first clarify my statement to my ’69 classmate (Lisa Howorth) regarding such. I never stated that racist kids did not exist at Whitman – that would be rather naive on my part. I clearly stated that I was never subjected to racist (to my knowledge) or disrespectful acts of racism while at Whitman. I was always treated with respect and kindness. During times of heighten racial tension, Former President Obama would often state that racism is a learned behavior. That is something I have always believed even before I heard it from him. A statement in this article by another classmate appears to support this belief. So, I raise the question to the ’69 classmate (Victoria Crawford) who stated “it was understood that we were better and they were worse” – without stating who the “we” and “they” are, is this the mindset that you were taught as a child and was this same mindset passed on to the next generation or was this racist cycle broken? I don’t mean to offend, but lets be real – people are not born racist, yet racism is alive and well. I am a proud alumni of Walt Whitman and I pray that Whitman will one day be the model High School for effectively addressing race relations.

Victoria Crawford • Mar 22, 2018 at 7:33 pm

Hi Philomena,

I appreciate your questions…..and it’s something I’ve been thinking about quite a lot since the opportunity to speak with Eric a few months back. I wondered how I ‘knew’ these racist beliefs without being taught them overtly. I never remember any conversations in my house directly speaking to this topic or anyone saying anything negative or critical outright, but……as a young child what I felt was very much what I shared with Eric. It was on a deeper level and it seemed to be part of the culture and unquestioned. Good question …was this passed on? I have not seen any evidence of that. I wondered when was it that I no longer sensed or felt what was quoted?….I think it was when I started thinking for myself rather than just accepting what was given or passed down. Hope that helps….let me know if you have any other questions.

Robert Strupp • Mar 9, 2018 at 8:52 pm

This is an excellent article. Thank you. I can really relate to this. In 1968, I was in 6th grade at Bannockburn Elementary where the principal was a Black female. In 2018, the Secretary of HUD is under fire for proposing to change the language of HUDs nondiscriminatory mission and I am the executive director of a fair housing enforcement nonprofit. Thanks again.

Roy Nichols • Mar 15, 2018 at 1:35 pm

Graduated in 67 with approximately 10 to 20 other blacks form WWHS and feel compelled to comment about my experience there.

Possibly because I was a popular athlete in most sports during my three years there, I never experienced any overt bigotry or predijuce whatsoever.

Loved the school, loved the teachers and had a great repor with just about everyone.

Ironically, in 1968 while attending Montgomery College in Rockville is when I encountered many blacks that had attended other Montgomery County High Schools

that had very different experiences.

1968 was such a volatile year throughout the entire country…

Go Vikes.

Roy Nichols