Media bias sways student news consumers

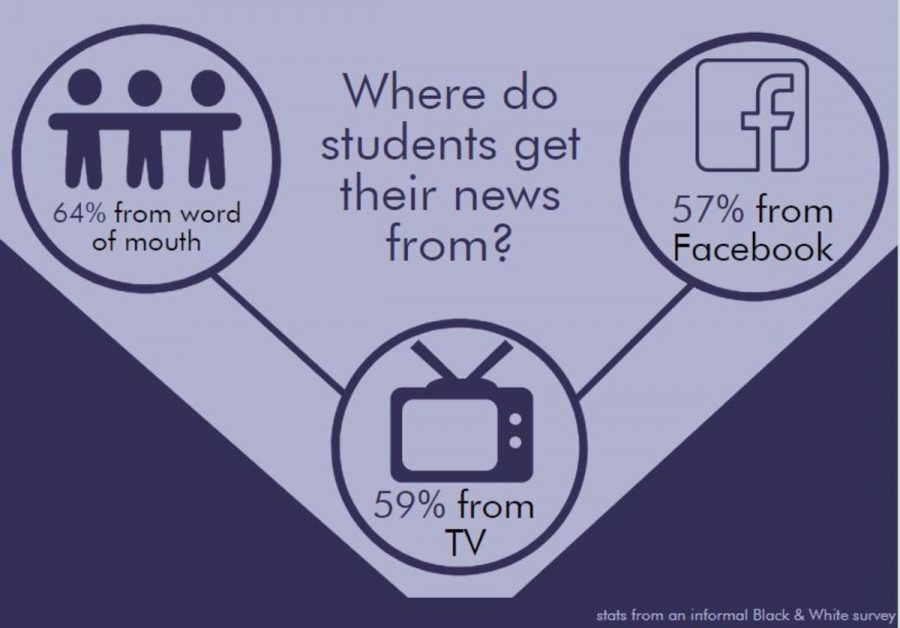

Graphic by Meimei Greenstein.

December 20, 2017

After President Trump responded to Hurricane Maria, BuzzFeed published a news article titled “Here’s What’s Really Happening In Puerto Rico, Despite What Trump Is Saying.” Former Fox News host Glenn Beck then wrote an article titled “Data Analysis Shows Media Only Covered Puerto Rico to Bash Trump.” Days later, The Hill published a different article: “Timeline: Trump’s Response to the Crisis in Puerto Rico.”

Many have also said that the presidential election was rife with media bias: voters blamed the media for shaping the outcome, and politicians, including President Trump, labeled many publications and news organizations biased. Now, hyper-partisan media and fake news may influence not just political outcomes, but citizen viewpoints as well.

For students like sophomore Clara Koritz Hawkes, coming across contradictory headlines is commonplace. Koritz Hawkes is skeptical about the accuracy of the news, so she often compares several articles on the same subject, she said.

“Depending on how important the story is, I’ll look at it on different platforms just to make sure that whatever I read in the first place was accurate,” Koritz Hawkes said. “I’ll look at the New York Times, and then I’ll look at BBC and then I’ll look at CNN.”

While Koritz Hawkes reads numerous center and left-leaning outlets, she often avoids right-leaning news. Though she’s curious about conservative outlets, she doesn’t believe they’re trustworthy, she said.

“I’m very politically passionate, and I don’t love reading things that I think are wrong,” she said.

Koritz Hawkes’ news habits align with the majority of Whitman students. In fact, 59% of Whitman students chiefly consume news media from liberal outlets, the Black & White found in a survey of 50 students across grade levels.

Student news preferences reflect a national trend: like Koritz Hawkes, Americans are consuming biased news that confirms their present beliefs, said Beth Jannery, George Mason University’s Department of Communication Journalism Director.

“If you already believe something to be true, you may not necessarily go digging to see if there is another side to it,” she said. “If you’re conservative, and you want to believe one thing, there it is. And if you’re on the other side, and you want to believe the other, there it is. It’s like these little battles playing out in the press.”

Don Irvine, chairman of Accuracy in Media, a right-leaning media watchdog organization, worries that editorialized news gives students a false impression of the truth, he said.

“I think that the students and a lot of other people get influenced by the fact that news reporting isn’t really news reporting anymore,” Irvine said. “It’s editorials disguised as news that give a false impression to students.”

To Jannery, who incorporates media bias and fake news instruction into her journalism classes, the prominence of biased news heightens students’ individual responsibility as savvy news consumers, she said.

“We have to work harder than ever to make sure that what we’re getting—the information that we’re reading, dissecting, putting into context—is fair and accurate,” Jannery said.

Jannery worries that students rely on BuzzFeed, which often uses unvetted reporting and anonymous sourcing, for news, she said. Still, its fast-paced reporting has a benefit: breaking “news in real time.” Buzzfeed embodies true fast-paced news, Jannery says, but she urges students to be skeptical of its sourcing.

For some left-leaning newspapers, media bias—once a cursed label—has become a marketing strategy, Irvine said.

“Now they’re willing to say that they’re trying to push out a liberal point of view and admit it,” Irvine said. “The landscape has changed so much, newspapers are in competition with online sources from all sides. I think that part of this is a way for them to say we’re still relevant and we want you to read us because we want to be the voice of the liberal.”

While many Whitman students are avid news consumers—some even check the news more than 10 times a day—31% of students surveyed responded that they don’t feel confident identifying fake news.

Traditionally, fake news has taken many forms, including misinformation campaigns, propaganda and clickbait, Jannery said. But with President Trump’s continued accusations of liberal-leaning media, fake news has achieved “buzz-word” status. Now, it has the potential to erode the free press.

“I think the long-term impact is going to be a complete separation of parties, not just along political lines but also in the press,” she said. “I fear state-run, state-regulated, nationally-regulated press, which we are seeing with Trump TV. That’s frightening.”

Because of the fast-paced nature of the press, students are quick to believe the first headline they see—even if it’s exaggerated or fabricated, Koritz Hawkes said.

To avoid biased material and identify fake news, Irvine recommends “reading across the spectrum,” he said.

Still, Jannery worries that media bias and fake news will have a permanent impact on transparent reporting, she said.

“It used to be the role of the journalist to report the news, report the facts, seek out the truth. We’re the fourth estate that holds policy-makers accountable,” she said. “I think that’s really changing.”