Con: The current academic requirement is enough

January 8, 2017

After attending morning classes and having a quick lunch, Whitman alum Anton Casey (‘15) heads straight for the weight room. Five hours of practice later, Casey eats dinner and then finishes the night studying at the library.

Many college athletes feel the stress of this everyday grind. To avoid putting increased academic pressure on students already pushed to the limit, the academic requirements already set by the NCAA in athletic scholarships should not be changed.

When athletes dream of making it big, the first step is usually playing at the college level. Scholarships are therefore highly sought-after rewards. However, obtaining one is no easy feat; balancing a sport and academics comes with tremendous pressure. Princeton basketball commit Abby Meyers said the process can be nerve wracking and overwhelming. While the pressure begins to build during the recruiting process, it doesn’t end there.

Thirty percent of the 195,000 college athletes reported having felt depressed in the last 12 months, and 50 percent reported having felt overwhelming anxiety during the same period, according to a recent study by the American College Health Association.

These stress levels are a result of multiple factors, including the pressure athletes place on themselves to meet their own standards. If their performance, either in the classroom or on the field, falls below success standards, an additional stressor is added: the fear of losing their scholarship. Scholarships can be crucial for an athlete, and losing it can be devastating, both for stability and self-esteem.

What makes this fear so real is that athletes have little influence over the terms of their scholarship. Although a coach cannot pull a scholarship in the middle of the year without a good reason such as ineligibility, scholarships are one-year contracts. It is entirely up to the coach to renew it, and they aren’t required by the NCAA to cite a specific reason if they don’t. Therefore, the only thing athletes can do is commit to their sport, and hope that their scholarship is renewed.

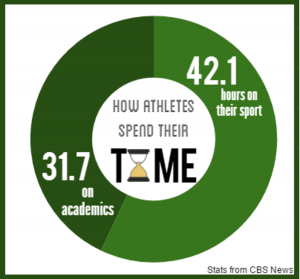

Because they must spend so much time practicing, most athletes don’t have the time for other things outside of practice and schoolwork. College men’s basketball and football teams spend an average of 39 to 43 hours a week training, despite the cap being set by the NCAA at 20 hours, according to Business Insider. This isn’t just limited to high-visibility sports. The average for all other sports, in both men and women’s athletics, sits at 32 to 33 hours. With the heavy time commitment, scholarships don’t provide unnecessary handouts—they provide financial stability for all their work reinforcing why the current academic standards should be maintained.

USA Today and Time have argued that colleges admit athletes who aren’t prepared to meet the academic workload of their schools, so the academic requirements to receive a scholarship should be made stricter. However, test scores are often a direct measure of socioeconomic status, according to the Stanford center for Education Policy Analysis. An increased academic requirement won’t ensure better, harder working or more deserving athletes are rewarded; it may simply ensure scholarship recipients are students with higher family incomes who could afford better test prep. Scholarships should be measured on athletic skills, not family income.

During the season, Casey returns to his dorm from the library at around 11, weary from a full night of studying. He goes to bed exhausted, ready to run the same cycle over again the next day. Athletes should be supported and valued, not forced to run themselves into the ground.