Pro: Colleges should rethink scholarships for student-athletes

January 8, 2017

Many football players recruited to play in college have extremely low SAT scores, according to the Atlanta Journal-Constitution. Take, for example, the average for Oklahoma State University football: 878 out of 1600.

By awarding scholarships to athletes like these, many schools celebrate their athletic ability but simultaneously send the message that academic success is less important. Colleges should create stricter academic standards for awarding scholarships. Special treatment for athletes who don’t measure up to a school’s academic standard is unfair to the rest of their students and hinders the athletes’ potential for success in the long run.

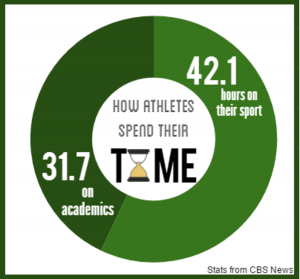

Because the majority of their time is spent on the field, athletes tend to not prioritize academics and earn poor grades, according to Scholar-Baller, a nonprofit that works to teach students how to balance both sports and academics.

In order for athletes to stay eligible, the NCAA requires that they maintain a minimum GPA—2.3 for Division I schools, and 2.0 for Division II. But at the moment, the average GPA for male football players is 2.46, according to the NCAA. At some schools, professors and counselors encourage athletes to load up on “paper classes, obscenely easy courses. If athletes begin to fail, professors ensure they keep their eligibility by awarding better-than-earned grades. This unethical practice, one that demeans other students’ honest work, can continue for years without being discovered, like in the case of the University of North Carolina (UNC) Chapel Hill. In 2014, multiple news outlets exposed the school’s 18-year-long record of academic dishonesty and grade fixing surrounding its student-athletes.

Recruits and colleges agree that sports scholarships are once-in-a-lifetime opportunities for students to further their athletic careers. However, about 98 percent of all college football players never go pro; only around 1.6 percent do. For other top-billing sports like women’s basketball, only 0.9 percent of players are ever drafted by a Women’s National Basketball Association team, according to the NCAA. The vast majority of collegiate athletes will never play their sport professionally.

Because they aren’t held to strict academic standards, these athletes often graduate unprepared to join the workforce, according to an investigation by Mary Willingham, a former UNC learning specialist. Willingham studied 183 UNC football and basketball players and discovered that 60 percent read between fourth- and eighth-grade levels. Eight to 10 percent read below a third-grade level. Denied a meaningful college education, such athletes are hard-pressed to get even entry-level jobs after graduation, Willingham reported.

In order for students to graduate having succeeded in all aspects of their college careers, colleges should only give athletic scholarships to both academically and athletically accomplished individuals. Extremely low high school GPAs shouldn’t be the norm when considering potential recruits; the average required by the NCAA should be a 2.7 or better. To make sure students maintain these grades throughout their college careers, a zero-tolerance grade-fixing policy should be established at all NCAA colleges.

Colleges like to refer to their athletic scholarships as “merit-based,” according to Athnet Sports Recruiting, insinuating that they’re rewards for hard-working individuals. However, this won’t be the whole truth until student-athletes are held accountable for their performance in the classroom and not just on the field.

Real Sports Fan • Jan 9, 2017 at 12:43 am

Do you think the players who read at a fourth grade level would ever get into a school like UNC without sports? An even larger question is whether many players could afford high education at all without scholarships. These players may not be the smartest players and they’re respective schools, and it may upset you that they’re accepted to prestigious universities that hardworking students like you may easily be rejected from, but the reality is that many of the players you refer to as inadequate wouldn’t have the opportunity to go to college or access tutors without sports. It’s understandable coming from Whitman that you want to point of the moral injustice of the recruitment system, but for some D1 athletes, this is their way of getting an education. Raising academic standards would only harm them. Before you write about how these players don’t deserve the education they’re getting, think of how many more opportunities you grew up with compared to how some of these players overcame obstacles to earn a scholarship.