MCPS: adopt teacher union’s start time plan

December 2, 2016

Nearly half of all adolescents in the U.S. get inadequate sleep, according to a survey by the National Sleep Foundation. Two factors contribute to this problem: teenagers stay up too late and their schools start too early.

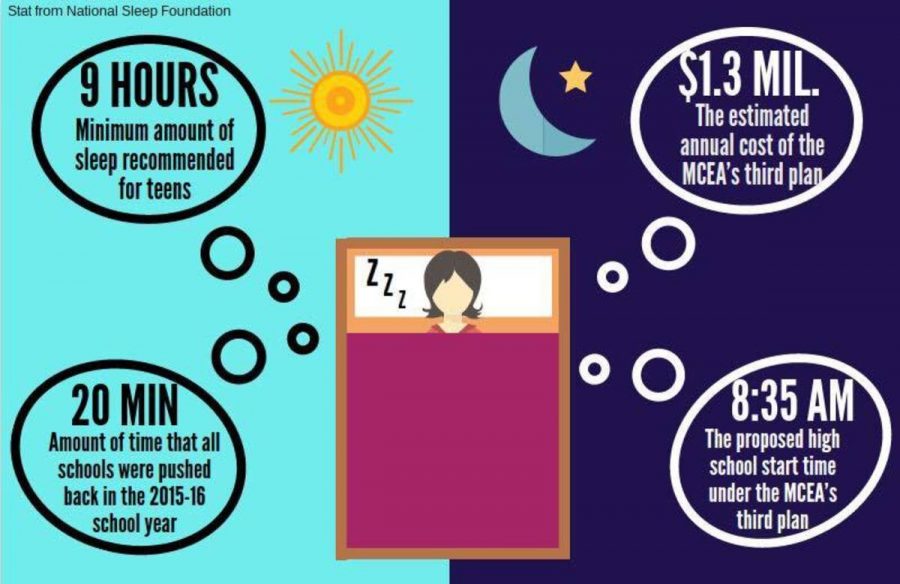

In order to provide students the opportunity to get the sleep they need and improve academic performance across the county, the Montgomery County Educators Association (MCEA) recently proposed three new plans to change school start times. MCPS should adopt the third proposal, which calls for high school start times to shift 50 minutes later to 8:35, middle school start times to move from 8:15 to 9:05 and elementary schools to start at 7:35 or 8.

MCPS has, to their credit, attempted to solve this problem in the past: former superintendent Joshua Starr brought up the issue in 2014 and eventually moved all school start times 20 minutes later. But this minor change wasn’t enough—even when it was initially proposed Starr said it wouldn’t solve the problem, only that it was a “move in the right direction.” The new 7:45 start time is still significantly earlier than the Center for Disease Control’s recommended high school start time of 8:30.

Moving start times back would help students get a healthy amount of sleep, which—despite the 20 minute shift from 2014—many Whitman students say they still aren’t getting. Teenagers’ circadian rhythms naturally shift later during adolescence, meaning many naturally fall asleep and wake up later, according to an NIH study. Early start times compound the problem, often preventing students from getting any more than 6 to 7 hours of sleep—nowhere near the 9 to 11 hours that the National Sleep Foundation recommends.

Despite possible benefits of later start times, many teachers remain opposed to them, according to an MCEA survey gauging interest in their new plans. Teachers doubt whether a shift in start times would actually improve student performance or lead to students getting more sleep, the survey found. However, neither concern seems to be play out when later start times are actually implemented.

First, students’ academic performance does improve with later start times; 9,000 students in three states improved their test scores and grades across all subjects when their start times were shifted later, according to a University of Minnesota study. This shift also boosted school attendance and decreased tardiness and substance abuse.

Additionally, teachers claimed that students would stay up later if start times are moved. This isn’t the case; students whose start time switched from year to year still went to sleep at the same time, a Brown University study concluded.

Opponents to changing start times frequently claim it will cost too much money. However, Starr originally proposed this plan in 2015 specifically to be a cost effective option—estimating an annual cost of $2.6 million. The MCEA puts potential cost even lower at $1.3 million. Relative to MCPS’s annual $2.46 billion budget, this cost is relatively insignificant.

The 20-minute delay wasn’t enough to combat sleep deprivation in MCPS. Adopting the MCEA’s newly proposed plan would finally fix the problem.