A culture of cheating: systemic roots and COVID repercussions

Students cheat for various reasons — college expectations, stress and pure exhaustion. These pressures have created an environment within the community that encourages academic dishonesty, creating a culture of cheating at Whitman.

June 6, 2023

Student names have been changed to protect anonymity.

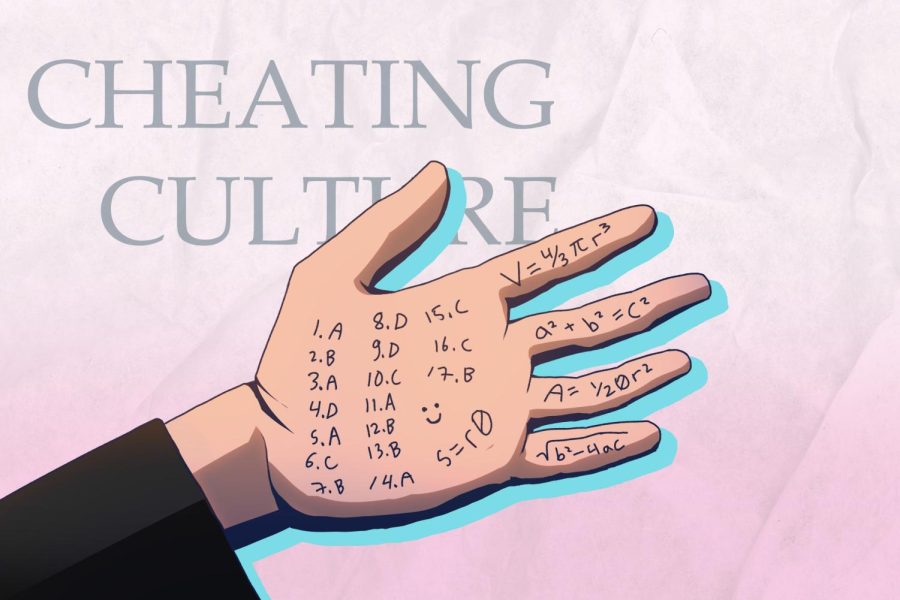

Sunlight filters through the windows on the fourth floor of the new wing. A student fidgets with their pen, clicking it on and off. They stare at the blank pages of their math test, the formulas they studied the day before now a distant memory. Discreetly, they pull their sleeve back, revealing rows of math equations inked on their skin. After a glance at the desired equation and a quick scribble of the pencil on paper, the student proceeds with the problem.

Students cheat for various reasons — college expectations, stress and pure exhaustion. These pressures have created an environment within the community that encourages academic dishonesty, creating a culture of cheating at Whitman.

Located in an economically well-off area, Whitman is known for having more resources compared to schools in underfunded regions of the county. As a result, colleges assume that students from well-off areas, such as Bethesda, have made full use of their resources, making exceptional grades a baseline requirement for top colleges.

MCPS grading policies only add to the push for high GPAs. The semester grade-rounding policy and the “50 percent” grading rule help to enable students to perform well while staying on top of extracurricular activities. However, these mainly serve to artificially inflate students’ grades, making lower GPAs stand out comparatively. This incentivizes students to obtain higher grades by any means necessary.

“A lot of people are very focused on college, and that’s what’s driving them throughout the entirety of high school,” sophomore Alex said. “It’s motivating what their extracurriculars are, it’s motivating which classes they take, and without a doubt, it’s motivating whether or not they’re going to cheat.”

A stark lack of time for studying is also a major contributor to the cheating culture at Whitman. Pediatricians recommend that teenagers get between eight and 10 hours of sleep each night; however, 73% of teenagers get less than the recommended amount, often a result of intense extracurriculars and rigorous coursework. Balancing various stressors while still getting enough sleep to be functional the next day can leave little time to complete the required work. This provides further motivation for students to be academically dishonest.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, many students used the internet and their friends as sources for tests and homework answers. Without feasible methods of supervision in the online setting, teachers were largely unable to penalize students for cheating. A distinct lack of repercussions fostered an apathy toward academic dishonesty, reinforcing its place in Whitman’s culture.

Most Whitman students experienced some semblance of online learning during their middle school years — a critical time in educational development in which students build study skills that help them to succeed in high school and college. According to a report conducted by the University of Chicago Consortium on Chicago School Research, researchers found that a 3.5 GPA in middle school correlated to a 50% chance of college success. Appropriate education during middle school prepares students to succeed in high school and beyond. However, the interruption of school by the pandemic didn’t allow students to establish essential learning techniques. Unable to develop the study skills necessary for academic success, many students resorted to cheating.

“I think that since the pandemic, when people were doing asynchronous work and [were] able to do all of their tasks off-screen and off the Zoom screen, the standards for what was completed had to be so much lower,” English Teacher Matthew Bruneel said. “There was a changed expectation about what intellectual property actually means.”

The growth of artificial intelligence has further inflamed this issue. Released in November 2022, ChatGPT quickly rose in popularity due to its writing abilities. Other previous cheating methods for writing often involved plagiarism, but ChatGPT doesn’t borrow writing from other places. Rather, it crafts a response by predicting the most logical next word given its present data. Because this writing is technically original, it’s not picked up by traditional detection, allowing students who cheat to go unnoticed by teachers. Students in English classes across Whitman have begun to use ChatGPT to write papers for them, sophomore Jamie said.

Despite the recent influx, cheating at Whitman existed before the pandemic. In 2015, a survey conducted by The Black & White found that nearly 70% of students cheated on tests, and 80% cheated on homework. However, 75% of students had qualms about cheating on tests and assignments but felt they were left with little choice due to the rigor expected of high school.

“I think a lot of people treat [school] like a game and college is the goal point,” sophomore Avery said. “They’ll do whatever they will [and] use any means they have to better their chances.”

Due to the rise in cheating, teachers have started altering their lesson plans and teaching methods. Classes have shifted to on-paper essays and timed compositions to mitigate the use of ChatGPT as a cheating device. Some teachers see this new environment as an opportunity to adapt their teaching styles in creative ways.

“For my own teaching practice, I always see this kind of as a personal challenge,” Bruneel said. “I use the shifting culture around cheating as a way to keep moving my practice forward and ensuring that students are giving me fresh, creative, fun and meaningful ways of demonstrating their understanding and mastery of the concept, which is really what grades are all about.”