MCPS: deflate grade inflation and reform the grading system

MCPS should reform its methodology so that semester letter grades are based on the numerical average of students’ quarter percentage scores, and it should begin allowing pupils to earn pluses and minuses.

May 22, 2022

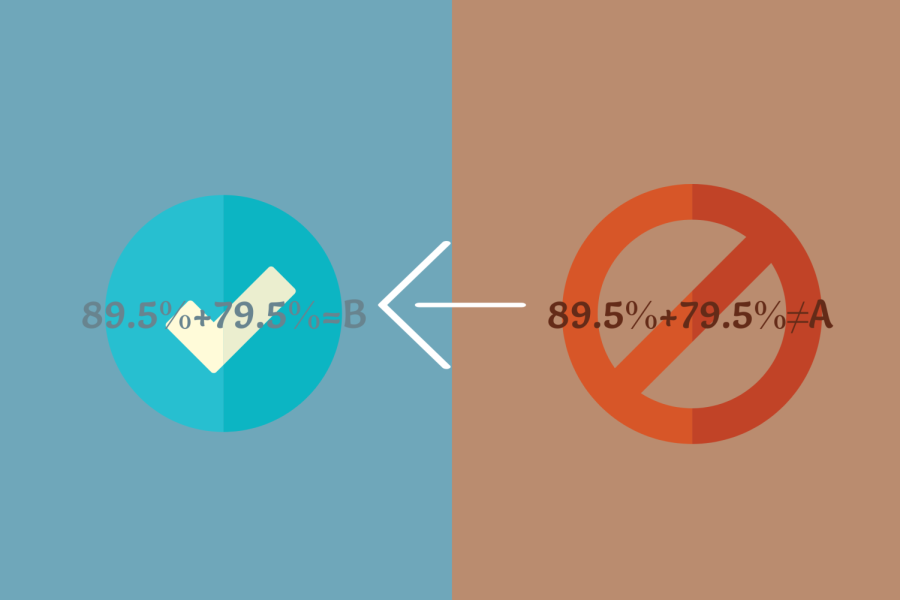

Picture this: one student earns a grade of 100% in a class during the first quarter, and another perfect grade in that class during the second quarter. A second student receives an 89.5% in one quarter and a 79.5% in the next quarter. When final grades for that semester are calculated, the first student receives a higher grade on their report than the second student. Right?

Wrong.

MCPS calculates semester grades not based on percentages, but by “averaging” a student’s letter grades from each quarter of that semester. Under this system, a student who receives a B — 79.5% to 89.49% — for both quarters receives a semester B. A student who earns an A — 89.5% to 100% — one quarter and a C — 69.5% to 79.49% — the next quarter also receives a semester B. Since the school district rounds up, a quarter A and a quarter B will always produce a semester A. Defying all known laws of mathematics, a student who earns a B and a C gets a semester B, and so forth.

Quarter grades don’t factor into GPAs, and they’re not on students’ transcripts. As a result, a student who got an A during the first quarter has no incentive to maintain that level of performance when they could simply earn a B, which would round up to a semester A.

MCPS’ grading system leads to grade inflation and incentivizes slacking. The school district should reform its methodology so that semester letter grades are based on the numerical average of students’ quarter percentage scores, and it should begin allowing pupils to earn pluses and minuses.

Under this grading system, a student who received an 86% in the first quarter and a 90% in the second quarter would earn an 88% for the semester. This would equate to a semester B+.

This new grading policy would directly curb grade inflation. The current system is ridiculously lenient, and it allows students to receive higher grades than they may deserve. In fact, the number of students who received semester A’s doubled after MCPS implemented the current grading system in 2016.

Grade inflation also decreases academic differentiation between students. Since 2016, MCPS’ “averaging” system has equated — on paper — the academic performance of students averaging an 84.5% with that of students averaging 100% over the course of a semester. To college admissions officers and internship coordinators, a student who receives a low B and a low C during two consecutive quarters looks just as qualified as a student who got two high Bs. This is unfair to students and admissions officials.

Pluses and minuses would increase the number of possible grades, allowing for greater differentiation between students. Moreover, averaging quarter grades would ensure that semester grades better represent a student’s capabilities in a class.

MCPS’ grading system also inherently encourages slacking. Since the district rounds up when averaging quarter grades, students who earn an A during first quarter lack an incentive to get a second quarter grade higher than a 79.5% — the lowest possible B — although they may actually be capable of achieving a higher score.

“I think that the semester grading policy reduces students’ incentive to be the best students that they can,” junior Jayden Ku said. “There are a lot of holes that students can find ways to crawl through just so that they can cruise straight by with a passing grade, instead of actually absorbing information.”

Averaging quarter grades could incentivize students to work harder for the entire year. If a student was aiming for a semester A- in a class and they received a first quarter A-, the student would need to get at least a high B in the second quarter in order to maintain their A-, rather than making it through the second quarter with a 79.5%.

In an informal Black & White survey of 31 students, 55% of respondents reported a decrease in the amount of effort they put into a class during the second or fourth quarter if they secured an A during the prior quarter.

Incorporating pluses and minuses into grades would help students stay engaged throughout the year because students would have to fight for every last percentage point of their grade. The final test of each quarter would matter much more for someone with an 85% in that quarter since their performance could make the difference between a B-, a B or a B+ for that semester.

Many proponents of the current grading system argue that increasing the difficulty of achieving a “good” grade would create stress for students. However, the opposite is often true. Many students currently spend an inordinate amount of time worrying about the difference between, for example, an 89.49% and an 89.5%, since one one-hundredth of a percentage point can drop students down from the supreme letter grade to the second-best out of only five possibilities. However, with pluses and minuses, an 89.5% and an 89.49% would go from being an A and a B, respectively, to an A- and an B+ — a less drastic contrast.

In addition, stress over grades may actually be a result of the current system. Rampant grade inflation leads students to feel that they must receive an A to be successful. In the same survey, 81% of students said that they aren’t satisfied with receiving a B in any class.

A larger variety of grades would reduce pressure on students to earn all As since it would be nearly impossible for students and their peers to each earn an A+ in every class.

While the transition to a more impartial grading system would force students to adjust their standards, this change would ultimately reinforce hard work, accurately differentiate learners, and prepare students for a world that doesn’t always round up.

Former teacher • Sep 14, 2022 at 11:45 am

It gets worse. Principals flin mcps force teachers to give passing grades to students who don’t show up or don’t participate for over 75% if the requirements but miraculously they make numbers out of thin air.

Lucy Goldberg • Jul 9, 2022 at 12:04 pm

Picture this: your depression gets worse and you need new medication, or you get sick and miss two weeks of school. Naturally, because you are in fact a human person and not a college-seeking automaton, your grades fall, but you finish a class with a 79.5. The next semester you work your ass off and you get a 92, and you’re relieved to be getting an A.

Everything will be okay, right?

Wrong.

The plan changes. All of a sudden you’re getting a B, in your junior year of high school, in a subject you’ve only ever gotten A’s in. You feel yourself beginning to spiral as you wonder what college admissions officers will think, and you start to hate yourself. Why couldn’t you have just gotten over it and used some Growth MindsetTM, or just not caught COVID? Finally, you pause tearing your hair out to wonder one simple question.

Why?

Well, because somebody assumes that he knows how much effort you put in. He assumes that you weren’t trying hard enough, and that’s why you failed. Or, maybe not you specifically, he knows you’re lovely, but you’re a casualty because he knows that Someone is slacking off and still getting an A. Well, surely if you’re a casualty, that means there’s some Noble Ambition, right? Well…. Not so much. Unless you count some other people’s egos. Does the adjective noble work in that instance? Maybe you’ll ask your English teacher.

If this prolonged hypothetical sounds far-fetched, that’s maybe because prolonged hypotheticals tend to lack substance. Additionally, an obvious lead-up like the one used is very predictable even if you didn’t know the policy.

More importantly, there is substantial a problem with any kind of argument that is based off “students are slacking oh no I must clutch my pearls.” First of all, what defines slacking? Slacking for an average Whitman student is probably watching a couple episodes of Netflix instead of spending that hour and a half studying.

That students reported slacking could mean that they took time for themselves, which they should be doing. During high school, I destroyed myself trying to get good grades, and am still suffering the repercussions of that prolonged stress. If I had taken some time to slack and allowed myself to breathe, I might not be rolling the dice as to whether or not I will need to be sedated the next morning from severe anxiety-induced chest pain because to my brain morning=school.

Moralizing around spending all of your time on school and only school hurts people. If the school’s policy allows for rest —which it does not entirely do— that’s all the more reason to not change it. People need cooldown time after working themselves to the bone for three months. It boggles the mind that someone would write and publish an argument to undo one of the few things the school has ever done correctly for mental health.

And, according to your own survey, 45% of students don’t even take that rest time.

If you can work non-stop with no significant repercussions to your health, good for you. That will likely bring you great success in life.

But let’s be clear: that makes you lucky. What it does not make you is better than the people who can’t. Your tone implies you think success in school is purely based on merit. That is not true. The school system is designed to reward those who require little sleep to function, are neurotypical (especially those with abnormally good executive functioning), have no other time commitments (such as work or family responsibilities), and/or those who learn to value nothing in life more than school. You’ll notice none of these traits are inherently virtuous. Despite one’s best efforts, performing poorly on one big test or another is almost inevitable. It is a rare good policy at Whitman that allows for the complexities of people’s lives to not haunt their academics.

Removing the current grading policy will hurt students’ resumes for college. Your article seems to think that that is some form of justice. It isn’t. Getting a few more points in an already competitive atmosphere doesn’t make you more deserving. You deserve college because of what you have done outside of school. You deserve college because everyone does.

Most relevantly, you deserve college because you worked hard for your grades. Hate to break it to you, that’s what the people you’re sneering at for getting 89.5s also did.

As for whether the current policy causes more stress, you’re missing the point. Whitman students will stress out about grades because Whitman teaches students that only perfection is acceptable to college. Making a minus and plus system won’t change that. If the difference between an A- and B+ is 90, students will stress over 89.8s. If the difference between A and A+ is 96, 95.5s will cause misery.

What you have changed is you’ve allowed students to personalize their anxiety, and I’ll give you credit for that. I didn’t think it was possible to make Whitman a more anxious climate, and you proved me wrong. By adding more grades, even students who were okay will now stress over the implications of a B- vs. a B+ and students who were finally happy with their grades at an A will worry about A- vs. A+. Any progress being made on helping students not stress about their grades and focus on learning will be undone overnight.

This additional stress contradicts your stated goal of keeping students focused all year. Instead of students enjoying and internalizing reading a book for English, for example, they would be focused on what the teacher will ask about, or what kind of answer the teacher is looking for. Yes, students will focus more on academics, but not in a positive way. Try remembering how to solve a parametric equation while one part of your brain focuses on a future test, another speculates on whether colleges will still accept you if your grade has a minus in front of it, another tells you this material will become the determinate of your future, and another tells you what history you learned last class will be the determinate of your future.

Heightened anxiety does not facilitate learning. I have tried, and it did not work. Yes that is anecdotal, but so is most of your theory on slacking.

Your survey hits some snags as well. With a sample size so small, a near tied result makes your majority meaningless. You have a 17-14 split, which not enough to base a whole prong of your article on. You’ve also hit a bit of a Post Hoc Ergo Propter Hoc problem. You did a survey on the grade system, and asked students how they felt about B’s. When they said they were distressed, you assumed that since that answer your survey was on the grade system, the grade system caused the distress. I’d argue a bigger factor is cultural pressure.

There are multiple potential stressors: college counselors who encourage the use of Naviance to obsessively track your stats, parents who make the same mistake you did about grade result=effort put in, peer pressure from constant discussions about grades and college, teachers calling you a moron if you do poorly on a test (yes Mr. Paulson that was a shout-out to you), etc. I could write an article around pre-college culture and use the same stat from the same survey.

What this comes down to is a question of self-aggrandizement. In theory, it makes sense that the people who did *so much better* should be rewarded for exceeding what was required of them. It’s understandable to want acknowledgement for going above and beyond. I did the best, I should get the only trophy. After all, you spend all your time and you get perfect grades and you want to think that you’re better, that you’re smarter, than other people. And you want everyone else to know it too. You want empirical evidence to validate your ego.

I fell into this trap at the beginning of high school. As my mental health started to worsen but my grades stayed perfect, I wanted something to show for it to make me think that my suffering had gotten me something other people didn’t have. It was too difficult to accept that maybe I wasn’t depressed to achieve hereto unachieved glory, but rather because I had allowed myself to fixate and skew my priorities. I wasn’t entitled to being “better” than everyone else because I was obsessed with my grades and ignored my friends. If people got my same grades while being healthier, that isn’t a sign that they didn’t deserve the grades, it’s a sign that I made a mistake or needed help.

That some people exceed the benchmark with no additional reward does not mean the benchmark needs to change. If you feel good about yourself for getting a 100, that’s great. But that doesn’t mean everyone should need to match you to get the same feeling.

As to your point about college admissions, AP classes grant the overachievers higher-weighted grades, allowing for college transcript differentiation. Thus, everyone’s grades do not all look the same. The problem is nearly nonexistent, while your “solution” will hurt people. Essentially, you are proposing to put out a trash can fire with a tsunami.

You would also be getting rid of the grace period for students who have a situational dip in performance. My grandfather died a few months ago, and I needed to ask professors for considerable extensions. High school teachers are rarely so generous, but the grading policy ensures poor performance one quarter does not doom the semester.

Ultimately, what this comes down to is that there is a reflexive desire by Whitman and those who do well in it to push the narrative that school is the only important thing in your life. Any potential leeway, even when designed to curb the mental health declines that inspired an entire book (“The Overachievers”), is anathema. Slacking is the ultimate crime because it shows an acceptance that life is more than a collection of test scores. In an extremely competitive area where nearly all therapists are booked, the piece that gets published is one arguing that people have it too easy.

My advice: just chill out. Allow —even encourage— students to put themselves and their health first if they earned an A one quarter. Stop caring about the grades of others around you.

I’m sorry if someone who got an 89.5 having the same grade as you makes you angry. I truly do hope that this piece was motivated by concern for others’ education. I encourage you to look more critically at how Whitman functions, and then to reassess whether the most pressing takeaway is that it should be harder for people.

Jeff Hornacek • Jul 14, 2022 at 12:39 am

for real

jim • Feb 20, 2025 at 1:57 pm

this is a whole novel