“Junk” isn’t junk

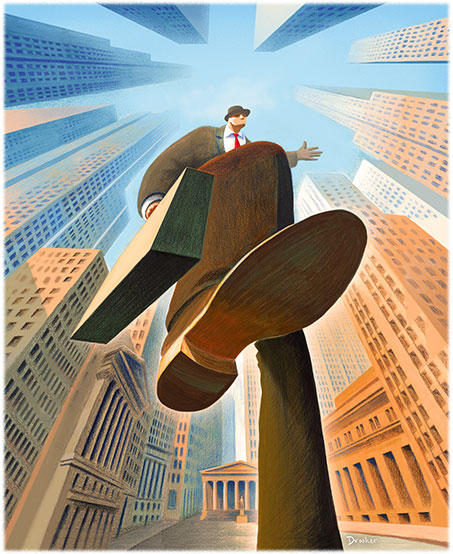

Director Jackie Maxwell turns the audience into extras in the play in a critical scene. “Junk” opened in D.C.’s Arena Stage April 11 and played through May 5.

May 26, 2019

Pulitzer Prize winning playwright Ayad Akhtar’s play “Junk” opened in D.C.’s Arena Stage April 11 and played through May 5. The show debuted on Broadway in 2016 under the title “Junk: The Golden Age of Debt.” The Arena Stage production features an all-new cast and stage.

The play focuses on the debt financing revolution of the 1980s on Wall Street. Tom Everson (Ed Gero) of Everson Steel works to stop Bob Merkin (Thomas Keegan) from taking over his family’s company. Merkin’s takeover proposal will be financed by debt in the form of junk bonds. Parallel to this storyline, the New York District Attorney’s office seeks to catch Merkin for insider trading.

While the original play was three acts and boasted a runtime of over three hours, the D.C. version has been trimmed to one act with a runtime of about 2.5 hours. The audience can feel the cuts; the blitzing pace keeps the play moving, and no scene—or even line—feels wasted or useless. Mirroring the speed of the industry change in the 80s, this fast-paced action adds to the chaos of the show.

The first thing that someone would notice about “Junk” is the language. Economic and legal terms fill about a quarter of play’s lines. As Black & White reporters and high school students, we’re not lawyers or economists, nor did we live through the stock market boom of the ’80s. Heck, we don’t even have mortgages. The good news, however, is that very little of the economic jargon matters in understanding the play. Director Jackie Maxwell finds unique ways to break down complicated economics, like when a lawyer explains the Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations Act to one of the laymen in the play as a means to explain it to the audience.

Unique staging also keeps the audience engaged in the plot. The four-sided Fichandler Stage auditorium allows for more exits on and off stage—from each of the four corners—and no audience member sits more that eight rows away from the action. The inverted-fishbowl stage allows Maxwell to turn the audience members into extras in the play. Toward the climax—when the Board of Everson Steel votes to accept Merkin’s proposal of $61 a share using debt financing—both Gero and Keegan make final propositions in a large auditorium to the shareholders: in this case, the audience. In that scene, the audience becomes part of the play.

But if meta speeches or complex economics aren’t your thing, no worries—the theme of Junk isn’t tied up in these specifics. Instead, it’s a relatable story about the struggle between morality and practicality, and the difficulty in letting go of the past. For example, Everson refuses to sell his family’s company, even when his advisors point out that funding through debt is the “way of the future.” This timeless struggle of whether to hold on to tradition or modernize helps the audience sympathize with Everson, and it gives them someone to root for among a slew of unlikeable characters only looking to turn a profit.

With fast-paced action, unusual staging, relatable plot and an economics crash course, “Junk” is well worth the trip to D.C.