Concussions impair students’ lives

Students suffer from repercussions long after diagnosis

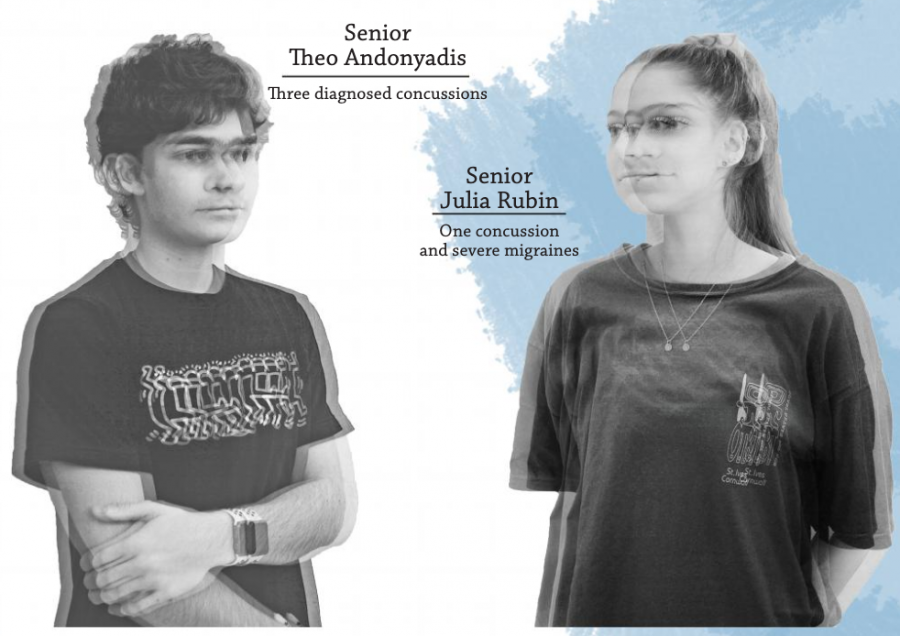

Three years after getting hit by a volleyball at practice freshman year, senior Julia Rubin is still suffering from the effects of her concussion.

As a freshman, she considered herself “bubbly,” played on the varsity volleyball team and looked forward to going to school. But since her injury, she has suffered debilitating migraines, which have forced her to take a break from sports and frequently miss school. At home, when she has a migraine, she lies in her bed in a dimly lit room, listening to TV shows with her eyes closed.

Rubin still deals with migraines a few times a week. She doesn’t know whether the migraines are a symptom of her concussion, though their severity and frequency has increased since her injury. This year, after a migraine attack, she quit volleyball.

“I just couldn’t handle it anymore. It was too much pain,” Rubin said. “My world revolved around sports for a really long time, and now it doesn’t. We’ve always watched sports in my family, but I’ve always liked to be the one on the court. I miss it.”

The American Medical Association found in 2017 that one in five teenagers will get a concussion, and of those teens, 33 percent will have at least two more that same year. But treatment for concussions is still a grey area. In recent years, most neurologists have told patients to rest in darkness until they feel symptom-free. But a recent landmark study by the University of Buffalo suggests that prescribed, individualized exercise can expedite recovery. And it was only last fall that the Centers for Disease Control developed its first guidelines for treating youth concussions.

Senior Theo Andonyadis has suffered three concussions since his sophomore year, forcing him to quit the varsity soccer team after his junior year. He was also diagnosed with post concussion syndrome, a disorder where concussion symptoms continue past the initial injury.

Constant headaches and dizziness force students with concussions to miss school for long periods of time. After suffering a concussion his sophomore year, Andonyadis skipped a week of school, then began going for half days. He would miss the first few periods and then come at lunch, or only come for the morning.

“It’s very hard on a student to deal with that, especially in this community where everybody’s working hard and you’re not used to being behind,” neurologist Carolyn Wang said. “We know that affects your sleep. If you’re not sleeping well, it starts to affect your mood and your anxiety and depression and focus and attention, too. So it’s very circular.”

When Rubin returned to school her freshman year, the transition was difficult academically and socially. Every class felt like a “foreign language,” she said. School has always been her priority, yet her concussion made it hard to do any work for more than a few hours, Rubin said.

She only went to two classes, so she didn’t see her friends or peers for most of the day. To avoid the noise of the cafeteria, she would eat lunch in an art classroom with some of her friends. But most days, she stayed with former principal Alan Goodwin, doodling in his office.

“I became very isolated and distant from my friends,” Rubin said. “A lot of my friends feel like I don’t care for them anymore because I don’t talk to them, but I just can’t. They understand that, but as much as they say, ‘it’s okay, take care of yourself,’ I know there’s a part of them that’s just like, ‘why don’t you ever ask how I’m doing?’”

Wang said that recovery time for concussions depends on a patient’s past history with certain symptoms.

“Some people will just recover in two weeks. Other people will take months,” she said. “If you go into a concussion and you’ve had a previous concussion, you’re more likely to have post concussion syndrome. If you go into a concussion and you’ve had a history of insomnia or sleep problems, or you’ve had a history of depression or anxiety, you’re more likely to continue to have these symptoms.”

This fall, Andonyadis suffered another concussion playing a pickup basketball game with friends.

“I’m so cautious about not wanting to hit my head anymore. I had gotten to the point where I wasn’t having many headaches and I felt normal,” Andonyadis said. “When I got hit, I knew how bad the consequences were. It was very disappointing.”

Andonyadis was in the middle of the college application process, and had incomplete grades from his absences, which colleges wouldn’t accept.

“It just became, ‘I have to get all my stuff done so I can make it into college.’ I had to spend all my time on mental work doing applications,” he said. “Some of my teachers were frustrated because I wasn’t getting their work done, but something had to give.”

English teacher Todd Michaels only had one concussed student when he began teaching in 2003. Last semester, he had four students, including Andonyadis, with concussions. He tries to approach each student based on their individual needs and circumstances.

“If it’s a serious concussion and the kid is unable to perform academically, we should do everything we can to be sympathetic,” Michaels said. “But we also have to find that balance between being sympathetic and realistic and maintaining proper rigor.”

Finding a solution to her migraines has been frustrating for Rubin. She has gone to different doctors, tried massage therapy, began acupuncture and changed her diet, all in hopes of at least lessening her symptoms. Still, she gets a headache most Sunday nights that usually lasts at least a few days.

For Andonyadis, doctors advised avoiding screens and noisy areas. He spent nearly three weeks lying in bed without the lights on, listening to albums and podcasts. When he came back to school, he struggled with the artificial lighting. He had to bow his head in classrooms and had trouble keeping his eyes on the Promethean Board for more than a few minutes.

Wang advises her patients to get at least nine to eleven hours of sleep per night, take naps and avoid blue light and strenuous exercise.

But neurologists are split on the best treatment method. Karen Laguel, the medical director at HeadFirst, a concussion clinic, said prescribed exercise is crucial in expediting recovery. Laugel said the treatment she prescribes to her patients coincides with the University of Buffalo study.

A former Whitman student (‘15) was also advised to lie in a dark room but struggled to recover from his three concussions in high school. His grades went “straight downhill,” he was unable to practice football and he started increasingly using recreational drugs. He noticed his head would feel better after smoking marijuana, so he and his friends began smoking it twice a day.

On the weekends, he and his friends would go to parties and experiment with drugs like LSD, opiates, variations of marijuana products and benzodiazepines.

“When I got that concussion, that was the point when recreational use and experimentation changed to everyday use,” he said. “When you’re under the influence of those drugs, in my experience, I was unable to do any sort of homework. That’s why I eventually stopped doing well academically.”

The next year, he began his first semester at a mid-size private university. He continued going to parties in college and started skipping classes. Before the first semester ended, he dropped out.

In the fall, he enrolled in Montgomery College and began pursuing an associate’s degree in business. Eventually, he hopes to transfer to the University of Maryland. He has also dramatically changed his lifestyle, quitting all the drugs he once used and even becoming vegan.

“If you asked me when I was 17 where I would be now, I wouldn’t say here. I’m not exactly where I wanted to be a couple years ago, but I know that I’m exactly where I’m supposed to be,” he said. “I have a future and direction, that feels good.”

Although he has experienced long-term effects, Laugel said, for some people, proper treatment can reduce symptoms in a matter of months.

“I think the pendulum has swung too far,” she said. “We have a lot of people now who are very fearful that when they get a head injury that it’s going to mean they have brain damage. It’s more common that people do quite well and heal normally and get back to their usual life.”

Rubin said that although she had to stop doing her favorite things, her injury gave her a chance to discover more about herself. The months she spent doodling in her room and Goodwin’s office made her realize her passion for art. Now, she wants to pursue a degree related to graphic design in college.

Still, she said she has good and bad days.

“Over the weekend, I was perfectly fine, super happy and for the first time in a really long time I felt like my normal self,” she said. “Then I woke up this morning just in this funk again. I couldn’t envision myself being that level of happy and bubbly, when less than 24 hours ago I could’ve taken on the world and done anything.”

With college coming up, she said she’s most nervous about her living situation. She has to go to bed early, not have strong smells in the room and not have too many people in the room at once.

Rubin doesn’t want her concussion to “define” her. Instead, she lets herself grow from it.

“It’s like when you can’t hear, your other senses are enhanced, it was the same thing with my concussion,” Rubin said. “I couldn’t play sports or go to school. Everything I knew was taken away from me and it gave me a chance to rediscover myself.”

Julia Rubin is Print Production Head for The Black & White.

12

Why did you join the Black and White?

Journalism is my first and only language.

What's your favorite scent?

THE CONSTITUTION (smells best in dim lighting)