Teach OCD in middle school health classes

May 31, 2018

Checking that the door is locked is normal. But checking eight times when leaving the house isn’t: it’s OCD.

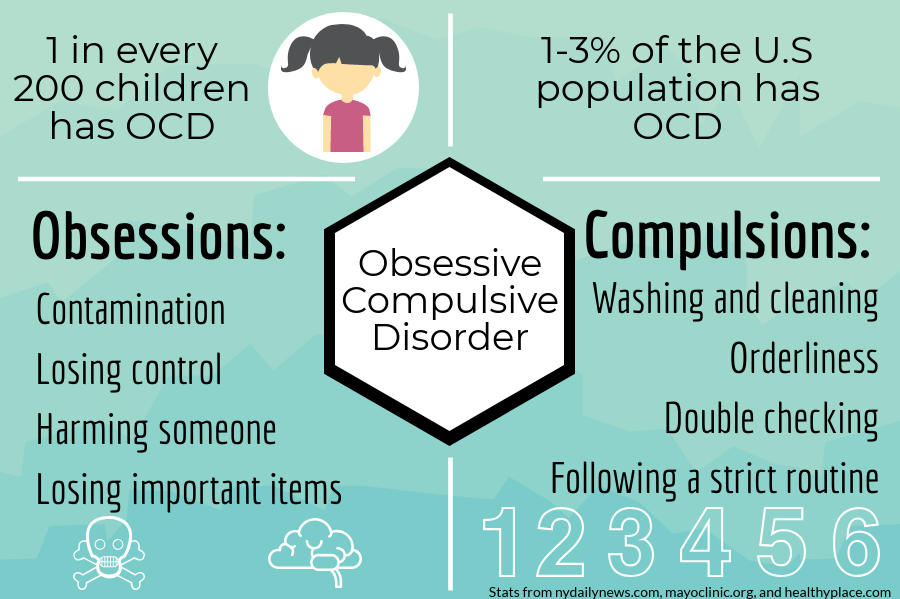

Symptoms of obsessive-compulsive disorder include unwanted and repeated thoughts, feelings, images and sensations. People with OCD often engage in repetitive and useless behaviors or mental acts. The mental illness can create hardships in every area of a student’s life, from social skills to schoolwork. An estimated 500,000 children have been diagnosed with OCD in the U.S. alone, according to the International OCD Foundation website.

In order to destigmatize this relatively common condition, MCPS should add OCD to the middle school health curriculum. Currently, OCD is touched on in the county health curriculum for the first time in high school. It’s not one of the “mental health challenges” specifically included in the middle school curriculum, Pyle health teacher Trina Hayes said.

When OCD isn’t taught, students don’t understand its gravity. They view symptoms as perfectionism rather than illness, leading to the development of a stigma which dismisses the legitimacy of OCD as a disorder.

Excluding information about OCD in health classes increases the likelihood of students failing to recognize the signs of the disorder and remaining undiagnosed. They’re led to believe that their obsessions and compulsions are only quirky behaviors, health teacher Nikki Marafatsos said. Educating students about the symptoms of OCD would familiarize them with the condition and teach those suffering that their “quirks” can be treated with psychotherapy or medication.

Additionally, teaching about OCD would inform students earlier that it’s a legitimate disorder, helping to eliminate stigma around mental illness. About 30 percent of Whitman students habitually use phrases like “I’m so OCD” to describe annoyances or imperfections, and 80 percent have heard peers express similar sentiments, according to an informal Black & White survey of 30 students. These expressions reinforce the notion that OCD is a personality trait rather than a mental illness, delegitimizing those who actually suffer from the disorder.

Opponents argue that teaching about OCD earlier on would detract attention from more common mental illnesses, like anxiety or depression. Although it’s true that anxiety and depression are more prevalent among teenagers, it’s not fair to discount OCD. Also, teaching about mental illness isn’t zero-sum: learning about one mental disorder can widen students’ perspectives and enhance their understanding of another.

Adding OCD to the middle school health curriculum would spread awareness about the magnitude and prevalence of the disorder, as well as give affected students a foundation to understand their condition. Though it’s a small step, putting OCD in the middle school health curriculum would bring us a little bit closer toward eliminating the stigma around mental illness.