Entertainment industry widens disabled representation

February 9, 2018

While physical and mental disabilities have been historically stigmatized in the U.S., the film and media industry has been part of a recent push to change the country’s attitude towards people with differences.

The movie “Wonder,” based on the book of the same title, does just this. Released Nov. 17, the film follows 10-year-old Auggie Pullman, a boy whose facial disfigurements—caused by a genetic mutation—leave him a victim of bullying and stereotypes.

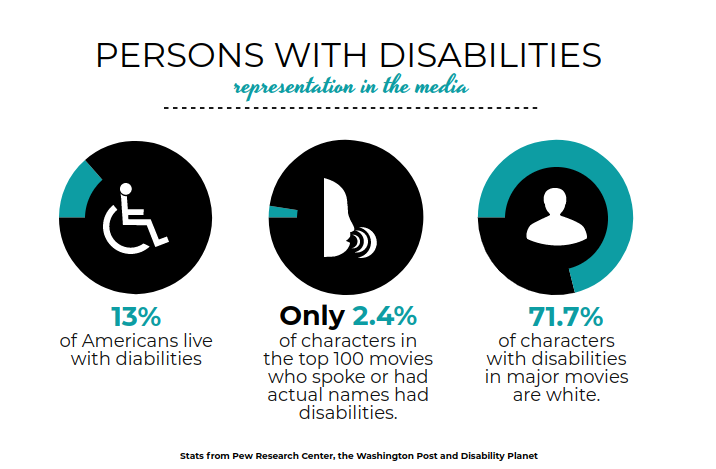

Over the years, the entertainment industry has increased the number of individuals with disabilities depicted in movies and TV shows. Still, only one percent of characters on television are openly identified as disabled, according to the Gay and Lesbian Alliance Against Defamation annual report of diversity on television. Conversely, nearly 13 percent of Americans live with a disability, Pew Research Center reports.

Anne Tucker, who has a son with autism at Churchill High School, recognizes the impact media representation has on her son.

“It has only been in the past five years or so that I started noticing characters with disabilities being portrayed in media,” Tucker said. “He is watching a TV show on Netflix now about a teen boy with high-functioning autism, and he really relates to him.”

Some of, these representations can be more unrealistic than beneficial. Characters are either incredibly ingenious or minimized. A study by psychologist Paul Hunt identifies 10 common stereotypes the media uses to portray characters with disabilities: pitiable or pathetic, an object of curiosity or violence, sinister or evil, crippled, laughable, his/her own worst enemy, a burden, non-sexual and unable to participate in daily life.

“When they are portrayed, the characters are usually a neurotypical person playing an autistic ‘genius,’” Tucker said. “While people with autism are bright, very few of them are geniuses, just like there are very few neurotypical geniuses. In terms of awareness of disability, I think it is appropriate to acknowledge what type of struggles living with the disability involves.”

In addition to the stereotypes, many shows and movies define characters by their disabilities. Various television shows, though, have transitioned to contain characters whose disabilities aren’t the primary aspect of their appearances on screen. Actor Russell Harvard, who plays Mr. Wrench on the popular comedy series “Fargo,” is deaf in real life and on screen, though his deafness is not designed to be his character’s primary trait.

Students who spend time with kids with special needs have the opportunity to develop heightened awareness of disability portrayal’s impact on self-esteem. Best Buddies club president Lily Tender says she feels it’s unfair to label and define someone based on their disability.

“I think if the character is viewed in a positive light and can advocate for themselves, it can be really inspiring and definitely raise self-esteem for kids with disabilities,” Tender said. “Kids with disabilities are so much more than their disability, and it’s important for TV shows to focus on their abilities.”

The Fox series “Glee” incorporated multiple characters with disabilities throughout its six-year run, including Becky Jackson, played by Lauren Potter, who has down syndrome, and Artie Abrams, played by Kevin McHale, who is paralyzed in the show, but not paralyzed in real life. The character proves to others that he could participate in activities like glee club and have fun, and is not in fact tied to his disability.

“You would never talk about me as ‘Lily with asthma,’ Tender said. “So why talk about someone as ‘So-and-so with down syndrome?’”

Organizations like Best Buddies focus on ending social, physical and economic isolation for people with disabilities while teaching them job preparation and important leadership and socialization skills through their one-on-one peer program. Whitman’s Designated Hitter elective also allows students to assist teachers in special education classes, working with students with disabilities in the Learning for Independence Program (LFI).

“Media representation for them can be harmful because it doesn’t show the spectrum of disabilities or what having a disability is really like,” junior Eleanor Wartell said.

Media representation for individuals with disabilities is also important for the development of kids without disabilities.

“A lot of times, people without disabilities don’t know how to act around people with disabilities or what to say to them, and can be hesitant to be around them,” LFI teacher Brooke Supinski said. “Raising awareness normalizes it.”

Many LFI students recognize the need for their own representation in media.

“It’s good to show differences in movies to everyone else,” LFI student Ella Matias said. “It’s important to show everyone disabilities on TV.”

Whitman LFI alum Dylan Kuhnhenn appeared as a paid extra on HBO’s movie Game Changer, which put out a call for extras with down syndrome. As an actor and viewer with a disability, he understands the importance of media representation for his community.

“When I was there, they treated me like a prince,” Kuhnhenn said. “It’s also important for audiences to see this and how they act in TV shows. I was watching ‘Law and Order’ [and saw someone with a disability], and I said to myself ‘They’re just like everyone else, and they’re portrayed in a positive light.’”

Although “Wonder” starts out with Auggie portrayed as a victim of bullying, he gains the strength and courage to advocate for himself. This inspirational film raises awareness around disabilities, and with it, the industry has taken another step toward normalizing narratives inclusive of disabilities.

Erin • Nov 3, 2022 at 11:17 am

I am absolutely in love with this article and graphic. You seem to have such a deep knowledge of this very complex issue. I’m actually using your article as part of a college research project. I am BEYOND impressed.

Meaghan Walls • Aug 26, 2021 at 5:05 pm

This is a great topic and an important one. Representation matters.

I am unsure what year the data you cited was reported, but I would like to offer a correction that a report by the CDC shows that 1 in 4 American adults have a reported Disability. It is also important to note that most disability related data do not include children, or capture the data on individuals with multiple disability types.

https://www.cdc.gov/media/releases/2018/p0816-disability.html

https://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/disabilityandhealth/infographic-disability-impacts-all.html#:~:text=61%20million%20adults%20in%20the,is%20highest%20in%20the%20South.