Combating sexual harassment in middle schools

March 12, 2017

Despite every middle school’s valiant efforts, cramming hundreds of pubescent kids into a building is an uncomfortable experience for everyone involved. Yet the most uncomfortable issue that emerges with the onset of puberty, is also the one least discussed: sexual harassment.

Sexual harassment is appallingly common in middle school, and unfortunately the incomplete education students receive on the topic facilitates this horrendous behavior. In order to comprehensively end sexual harassment among students and abide by Title IX’s sexual harassment standards, MCPS should update the health curriculum to ensure sexual harassment is properly addressed beginning in sixth grade.

While sexual harassment is often perceived as only happening on the street or in the workplace among adults, 43 percent of middle schoolers have been the target of verbal sexual harassment and 21 percent have been the target of physical sexual harassment at school, according to a recent five-year study of 1,300 middle schoolers by the University of Illinois. The study found that the majority of the harassment experienced by middle school students was perpetrated by peers and occurred most often in hallways and classrooms—locations that should have been monitored by teachers.

Legally defined as “unwelcome sexual advances, requests for sexual favors, and other verbal or physical harassment of a sexual nature” by the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, sexual harassment can be hard to identify in real life—especially for young students. When asked to describe sexual harassment, Pyle middle schoolers could identify extreme cases, such as rape or openly bullying someone because of their sexuality.

But the more prevalent, yet nuanced forms of harassment—like lewd jokes and comments about someone’s body or sexual activity—escaped them. Verbal harassment is the most common form of sexual harassment in school settings, according to a nationally representative 2001 study by the American Association of University Women (AAUW). Instances such as someone asking or teasing a girl about her bra size, making a sexually explicit comment about someone for being LGBTQ or spreading a sexual rumor are all forms of sexual harassment students may have unknowingly seen or experienced.

While sexual harassment is comprehensively addressed in the MCPS health curriculum, the topic is addressed far too late. The current curriculum first brings up sexual harassment in the eighth grade, even though students experience sexual harassment as early as sixth grade, according to the University of Illinois study.

MCPS must acknowledge the prevalence of sexual harassment among students in middle schools and take more serious, concrete action to prevent it.

The result is that instead of understanding these behaviors are wrong when they first experience it, victims internalize that these actions are acceptable and become perpetrators themselves—creating a dangerous cycle.

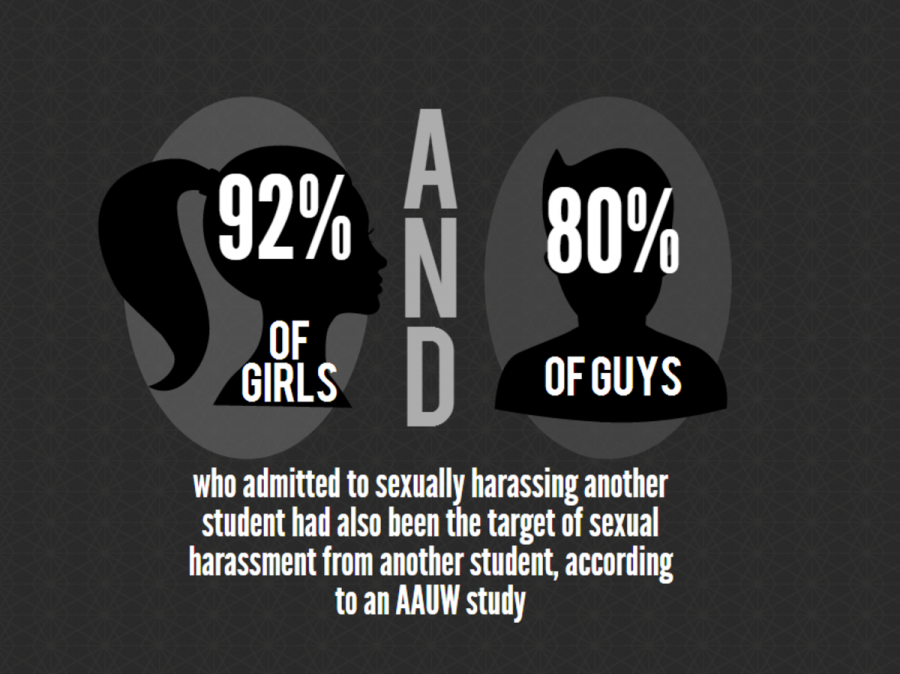

Ninety-two percent of girls and 80 percent of boys who admitted to sexually harassing another student had also been the target of sexual harassment from another student, a follow-up study by the AAUW found in 2011. Yet when asked to describe the events themselves, 44 percent of the perpetrators said it wasn’t a “big deal” and 39 percent said they were trying to be funny.

At that age, most verbal harassment cases spring from students saying things without thinking through the consequences of their words, Pyle health teacher Trina Hayes explained.

Though student perpetrators often don’t recognize their actions to be malicious, harassment profoundly affects the victim, regardless of intent. Victims of sexual harassment are more likely than other students to experience depression, loss of appetite, sleep disturbances or nightmares, low self esteem and feelings of sadness, fear or shame. Sexual harassment can also affect the victim’s school performance, leading to increased absenteeism, poorer grades and decreased quality of schoolwork, according to a University of Southern Maine study.

MCPS must acknowledge the prevalence of sexual harassment among students in middle schools and take more serious, concrete action to prevent it by changing the curriculum to include sexual harassment education throughout all three years of middle school.

There’s no changing the fact that middle school is an awkward time period, and full of all sorts of uncomfortable new experiences. But being the target of lewd comments or uncomfortable innuendos shouldn’t have to be one of them.