Country music: why it’s not all about farms and trucks

The Ryman Auditorium, which now hosts a bluegrass series each summer, used to house the Grand Ole Opry, a radio show that popularized country music. Photo by Lily Friedman.

January 10, 2017

For years, my dad filled the long drives to soccer tournaments in his Ford Explorer with the Beatles, Aerosmith or old Nelly. Although I don’t drive a truck, live in the woods or wear camo, I now flood my car with country music.

Many people in Bethesda, including some of my close friends and family members, can’t stand country, and I respect their opinions. I can deal with groans when Johnny Cash plays on shuffle in the car, but when people denounce the whole genre, I have an issue.

I’ve always liked country, but this summer I unexpectedly found the real reasoning behind my infatuation with it.

My moment of euphoria took place in the back of the Ryman Auditorium, a 2,362-seat theater in Nashville, Tennessee, which once served as the home of the Grand Ole Opry. Earlier that day, I’d managed to buy a single standing room ticket to see country music icon Vince Gill in a Bluegrass series at the historic venue.

At first, the mass of cowboy hats and boots in the small venue made me nervous; I was a 16-year-old Bethesda girl alone on a Friday night in the part of town dubbed “Nashvegas.” But as soon as the lights went down, I only focused on the music. The Ryman is famous for its perfect acoustics, but I never could’ve imagined that music could sound as pure as it did in that theater.

I pinpointed what connected me so emotionally to what I heard after a few songs: Gill’s lyrics. Gill crafted his words to capture his emotions in the same simplistic way that Johnny Cash, Patsy Cline, Hank Williams and Willie Nelson’s words aimed to communicate complex feelings decades before on the same stage.

Like Gill, many people in Nashville still honor old artists’ messages by emphasizing country music’s emotional nature rather than the “redneck” reputation that drives many to despise it.

For example, in one specific song, A World Without Haggard, Gill abandoned his band, traded his mandolin for an unplugged acoustic guitar, and sang about the recent death of Merle Haggard, another country legend.

Gill’s description of Haggard’s death was basic, blunt and strikingly negative. Just as many country artists state their meaning directly, Gill didn’t sugar-coat how it felt to lose his mentor and dear friend. That simplicity seemed to reach me personally, and I mourned Haggard’s death that night along with everyone else in the room.

I felt empathy for Gill because of the emotions attached to his music, but my greatest draw from that night is that my connection to the music isn’t exclusive to that historical venue. Just as Gill and other Nashville artists intend, I feel the same clarity that I felt that night every time I sit and listen to real country music. Whether I’m in the Ryman or driving home, I still feel something during a good country song.

Some people just don’t like country music, and that’s fine. But invalidating my experiences with country music isn’t just annoying to me: it’s borderline offensive.

I get that some country has devolved to trite narratives focusing solely on trucks, women and liquor, and sometimes there’s value in listening to catchy country. Yet it isn’t fair to label a whole genre as “redneck” or “trash” based on a few songs, especially when the purpose of most country music is to tell a story.

And I’ll admit I’m biased. I play Miranda Lambert on the guitar, belt Kenny Chesney in the car and hang posters of Elvis Presley in my room. But there’s more to country than a banjo and a twangy accent.

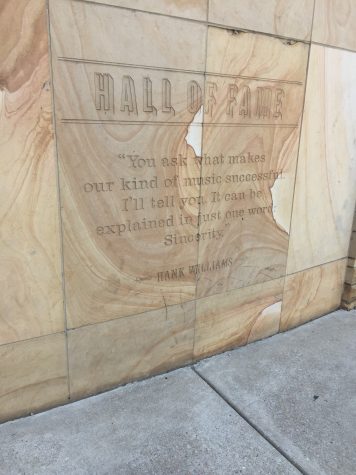

Written on the side of the Country Music Hall of Fame in Nashville, Hank Williams’ words perfectly describe why country music’s base has only grown in the past 75 years.

“You ask what makes our kind of music successful,” Williams said. “I’ll tell you. It can be explained in just one word: Sincerity.”

You may not enjoy it yourself, but until you understand it, don’t diss country.