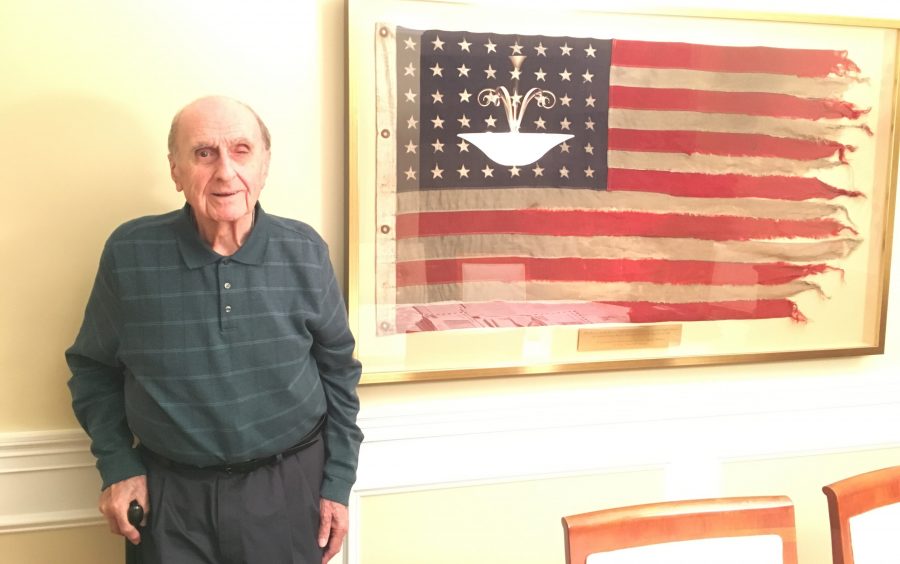

Q&A with former Quartermaster from Omaha Beach

Former US Quartermaster Stephen Berberian stands beside the flag that flew on the ship he steered across the English Channel to Omaha beach on D-Day. Photo by Jennah Haque.

November 15, 2016

I thought that having lived in Bethesda my whole life, I had found all the hidden secrets in this town.

Yet quietly, all this time, tucked in a townhouse right by Walter Johnson, lies a real hidden treasure. Not only for Bethesda, but for America.

His name is Stephen Berberian. He sits with his legs crossed, says “parlor” instead of living room, and is the sharpest 90-year-old I know.

Oh, and he stormed Omaha Beach in World War II.

Though a quiet man with a kind soul, Berberian is a venerable warrior. When people talk about the Greatest Generation, now I can say I have met someone who was an important part of it. Even though these next words can’t begin to encompass his irreplicable persona, hold onto his every last sentence. Put yourself in his white uniform, combat boots and sailor hat. Listen to a hero who made history defending our country and still lives today to tell it.

This interview has been edited for clarity.

Black & White: Tell us about how you joined the military.

Stephen Berberian: I enlisted in October 1943 at 17. I knew I was going to get drafted, but I didn’t want to join the Army. Instead, I enlisted for the Navy. My parents initially didn’t want me to go. My whole family came into my house and we had a meeting in the parlor. They asked my parents, “Do you want your son to sleep in a foxhole or a bed with sheets?” Eventually, my parents agreed.

B&W: What did it feel like once you had left?

SB: At first, lonely. I wanted to go, do my duty, get discharged, and come home. I got pretty close with some bunkmates. I brought my clarinet and we had jam sessions. I got to see the world too. My favorite was London and Paris. There was always an adventure.

B&W: What’s your favorite traveling story?

SB: We had a leave in Normandy, and our officers said we could go anywhere except Paris. Our crazy cook said we should go anyway. He forged a note saying we could go to Paris on official business and he signed the skipper’s name. We hopped on a mail truck in the morning and sat in the back for five hours. We’d sleep in the day and then go out at night to avoid all the military. Eventually we got caught and went to Bastille—one of the biggest prisons in France—for two weeks. The crew called us jailbirds after that.

B&W: What was your specific role in the Navy?

SB: I was a Quartermaster, so I steered the ship. Our ship was about 105 feet long and had a crew of only 25 men and two officers. Our job was to hit the beach bringing food, equipment, ammunition, troops, back and forth to soldiers for two months.

B&W: When were you most afraid?

SB: Halfway across the Atlantic, our engine broke down. We were traveling in a flotilla, so we were one of 30 ships. The rest of the flotilla left, and one destroyer plane escort stayed back. All of a sudden, the plane started dropping bombs (we called them ash cans then) because they were detecting a submarine shooting torpedoes. We were sitting ducks out there for hours.

B&W: Did you contact your family?

SB: On the back of your jacket, your hometown was written. I had Newark on my back and a merchant marine approached me. We actually went to the same high school. He was going home soon, so I asked him to deliver a note to my dad at his grocery store. Later, my dad wrote me saying he got the letter. All this time, he said, he wasn’t sure if I was dead or not. He said he was grateful for the marine and that I was alive.

I was a kid seeing people starving and dying. It makes you grow up. When you come back from war, you’re a man more than anything else.

B&W: How did it feel representing your country?

SB: I felt honor and pride for my country. There could not have been more of an honorable place than Omaha Beach at D-Day. So many weren’t lucky enough to make it back. I was a kid seeing people starving and dying. It makes you grow up. When you come back from war, you’re a man more than anything else.