The Generation After

As Holocaust survivors dwindle, who will be left to tell their stories?

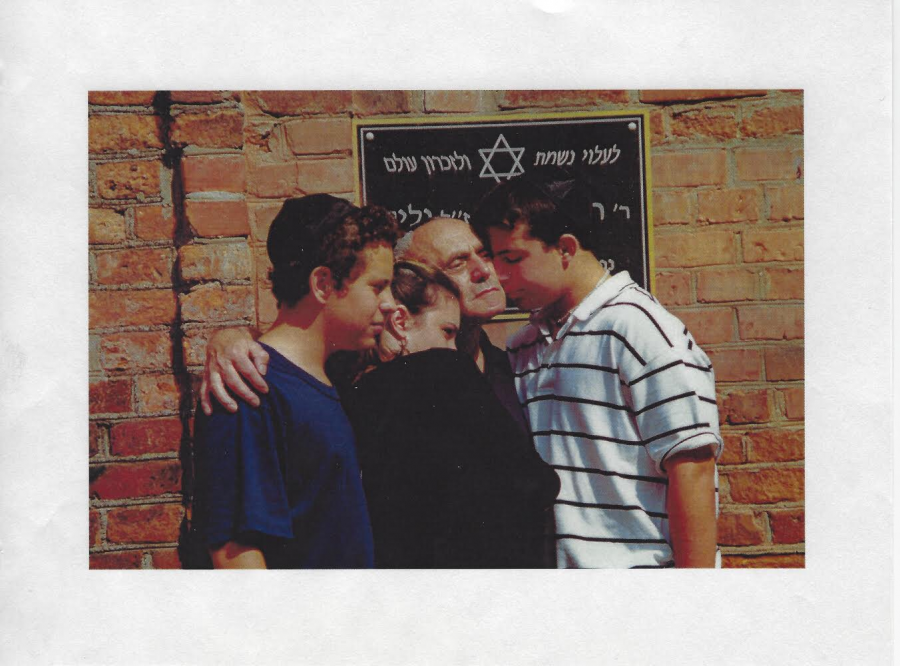

Barbara Brandys’ father, a Holocaust survivor, stands with his grandchildren during a 2000 memorial ceremony at a Jewish cemetery in Poland. Brandys lost her aunts, uncles and grandparents in the Holocaust and was forced to leave Poland for Israel in the Polish Communist regime’s purge of Jews in 1968. After moving, Brandys said she lost a sense of her Jewish heritage. Photo courtesy Barbara Brandys.

We’ve visited the Holocaust Museum. We’ve read about the Holocaust and learned about the millions of lives lost. But as instances of anti-Semitism increase globally and the number of survivors rapidly decrease, the Holocaust is becoming a distant historical moment, referenced only in textbooks and museums. For survivors and their descendants, their experiences contain invaluable lessons they’re trying to preserve. With insight into profound hatred, suffering and strength, survivors want to pass these lessons onto future generations—before the survivors are all gone.

Worldwide, anti-Semitic rhetoric and attacks are on the rise. Marine Le Pen, whose party has been accused of anti-Semitic remarks, earned 34 percent of the vote in the 2017 French presidential election. Last February, the Anti-Defamation League released its annual report, which found that the number of anti-Semitic incidents worldwide had increased by 60 percent from 2016 to 2017; it was the largest single-year increase on record and the second highest number reported since the ADL began reporting in the 1970s.

In October, a gunman opened fire on a Pittsburgh synagogue, killing 11 in what’s believed to be the deadliest attack on the Jewish community in U.S. history.

Even with a large Jewish community, Montgomery County residents have been the target of anti-Semitic hate crimes. In 2016, swastikas were painted at Burning Tree Elementary School, Westland Middle School and Richard Montgomery High School. In 2017, Charles E. Smith Jewish Day School received a bomb threat, and a Jewish sophomore at Churchill High School received an anti-Semitic text message. Just last month, swastikas were found drawn on a desk at Churchill. Statewide, from 2015 to 2017, reports of anti-Semitic incidents have risen 1,006 percent, according to the ADL.

Holocaust survivor Ruth Cohen photographed at her home this February.

This increase has especially worried survivors.

“People haven’t learned from the Holocaust,” survivor Ruth Cohen said. “What scares me is thinking about new generations who will never know that a mass genocide happened because people were racist and didn’t stand up when they saw people being taken away and murdered.”

Now, survivors’ children and grandchildren are asking themselves: what can we learn from survivors, and how can we ensure their legacy is preserved?

Survivors leave a generational legacy

Recent studies, including a 2016 National Institutes of Health report, have found that Holocaust survivors themselves aren’t the only people who suffer long-term effects from the genocide; trauma and resilience are passed down to their children and grandchildren.

Whitman parent Mimi Darmstadter’s father, Joel Darmstadter, grew up in Mannheim, Germany. At the age of five he was expelled from school and his father lost his job because they were Jewish. Their home was destroyed during Kristallnacht, a night during which Nazis legally burned and vandalized synagogues and Jewish homes across Germany. Darmstadter and his brother were sent to Britain under the Kindertransport program in 1939, a nine-month rescue effort to relocate about 10,000 refugee children from Nazi-held areas.

“It was scary,” Darmstadter said. “I had English skills that were very limited, and there my brother and I were: on a train, alone, without our parents or knowledge of what would come next.”

That same year, before Hitler enacted his “Final Solution,” Joel’s father was released from Dachau, a concentration camp, while Joel and his brother were “adopted” by a Jewish family in Manchester. But as the British government anticipated German bombings, they ordered children to evacuate from cities, and Joel was sent to live with an unsympathetic family, he said. Months later, he, his brother and his parents obtained visas and moved to the U.S. They later found out that Joel’s maternal grandparents had died in gas chambers.

Mimi said her father’s experience has shaped her personality. Growing up, she was taught to appreciate inclusion and diversity.

“I was raised believing very strongly—and having it demonstrated for me—that you don’t discriminate and that everyone’s equal,” she said. “My dad’s Holocaust experience and his personality have made him a very sensitive soul and very other-oriented; he doesn’t think much about himself but thinks a lot about other people. I think those traits have been passed on.”

But for some children of Holocaust survivors, inherited personal trauma defines their childhood memories.

Barbara Brandys is the daughter of Holocaust survivors and had her own painful upbringing in Poland. During her childhood, the Polish communist regime’s 1968 purge of Jews forced her family to relocate to Israel.

When Brandys moved, she felt distant from her Jewish heritage because her parents’ trauma made them reluctant to talk about Judaism, she said. Brandys wanted her own children to form the strong Jewish identity she hadn’t had in her youth, so in the U.S., she sent them to Jewish preschools and day schools.

Her parents were still emotional about their family members’ deaths in the Holocaust and effectively becoming orphans, so Brandys grew up knowing she could never ask about her grandparents.

“My father’s sister had long, dark braids,” Brandys said. “His last memory of her was seeing her pretty braids shaved off, and then he never saw her again. When I was growing up, my father made me have long braids. One day when I was about 16, he had been gone on a trip, and I cut off my braids. When he came back, he felt like I had personally betrayed him.”

Brandys said she sometimes had to think about the emotional needs of her parents before her own. Often, when she or other family members were flying to visit Brandys’ mother, her mother would stay up all night with a radio by her bed, anticipating news that their plane had crashed.

“When I had a flu or a high fever, my mother used to come into my room at night and kneel down to see if I was still alive,” Brandys said. “Because of her trauma of living through the Holocaust, there was no margin between bad things and death. That fear of things going wrong has definitely passed on to me.”

Two of Adam Weissmann’s grandparents were Holocaust survivors. Weissmann said learning about his relatives’ experiences in the Holocaust has shaped his outlook on life.

“Even as a small child, I’ve always had the sense that my life was an accident and that I have to make it count,” Weissmann said. “I’m not just living for myself; I’m living for all the people who weren’t born because their would-be grandparents didn’t survive. I have a special mission like other grandchildren of survivors to live more, and that’s not always an easy thing.”

Descendants continue survivors’ legacies

Senior Emily Schweitzer, whose great uncle—along with all of his immediate family— survived German concentration camps, said she was bullied when she was a freshman for being Jewish; she often heard anti-Semitic and Holocaust jokes in school, she said. After writing about her experience during an anti-bullying activity in her class, English teacher Omari James helped her create and deliver a lesson to classes about anti-Semitism and her family’s experience in the Holocaust.

“If people don’t hear from survivors or don’t learn about the details of the Holocaust, ignorance, anti-Semitism and Holocaust denial can thrive,” Schweitzer said. “I’m worried that losing a face-to-face aspect when survivors pass away could worsen anti-Semitism, but I’m optimistic that there are resources and people out there who want to educate new generations about the Holocaust.”

22 percent of U.S. millennials say they haven’t heard of the Holocaust or don’t know if they’ve heard of it

— A 2018 study by the Conference on Jewish Material Claims Against GermanyWhile teaching at a middle school in Arkansas, University of North Carolina student Noa Borkan, the granddaughter of Holocaust survivors, was asked to speak to seventh grade English students who were learning about the Holocaust. Her relationship to survivors helped her personalize the issue, Borkan said.

“It was a very strange experience since they were so disconnected from the story,” Borkan said. “I was the first Jew they had ever met—let alone someone connected to the Holocaust. To them, the Holocaust was this distant historical event. When I was growing up, Holocaust survivors always told us we would have to continue their legacy because soon no survivors would be alive to tell their stories. In that moment, I really felt that.”

Several groups, all with the goal of educating future generations about the Holocaust, have formed. The Generation After, a D.C. area group of survivors and their descendants, works to teach people about the Holocaust and to continue the legacy of survivors and those lost. One of the group’s projects is Remember a Child, a program that matches Jewish students preparing for their Bar and Bat Mitzvahs with the names and stories of children who died during the Holocaust before they reached their Bar or Bat Mitzvah.

Brandys leads the program.

“I feel like The Generation After is a very natural place for me to be normal,” she said. “My parents’ experiences in the Holocaust is always in the back of my mind—always to remember, always to try to continue their legacy, always to look out for people who deny the Holocaust or say something anti-Semitic.”

Weissmann is a member of a group similar to The Generation After, called 3GDC.

“My grandchildren will never have the chance to see my grandmother’s face turn to stone when talking about her mom and dad and brothers, what they were like, and trying to convey what it was like for her to lose them,” Weissmann said. “Nothing can convey that. I have to do my best to be a conduit and to explain to them what happened and how personal it is to me. That gives my generation a unique role; we’re the bridge between memory and legacy.”

The original article appearing in the March 2019 magazine incorrectly stated that Joel Darmstadter’s parents were both released from Dachau. Only Darmstadter’s father was sent and later relased from Dachau.

12

Why did you join the Black and White?

To learn more about the Whitman community and share news with others.

What's your favorite scent?

A campfire