When classrooms become a boys’ club

December 12, 2017

Walk into a Whitman classroom, and most students will appear similar. Students sit at identical desks, use identical Chromebooks and complete identical worksheets. But ask them a question, and a disparity will emerge: the students raising their hands are overwhelmingly male.

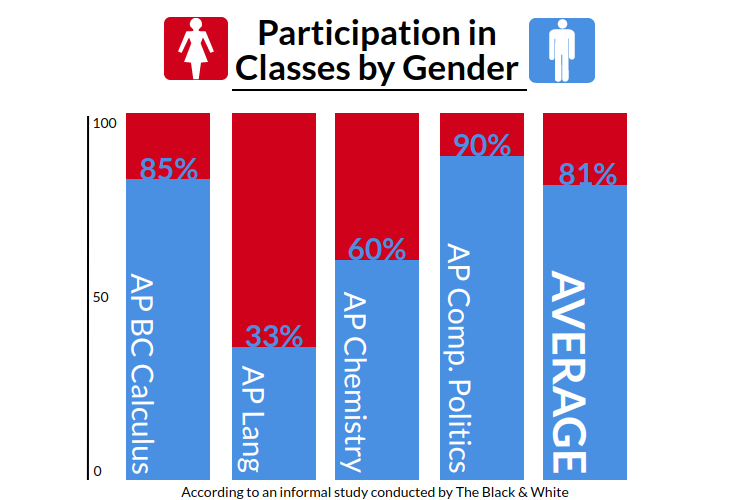

Since elementary school, I’ve observed this imbalance, but peers assured me the disparity was all in my head. So, last month, I finally set out to confirm my perception empirically. For one day, I tallied the number of female versus male participants in four of my classes, including AP Calculus BC and AP Comparative Politics, where participation is both frequent and voluntary.

The results were startling: overall, boys participated 3.1 times more than girls, even though the total ratio of boys to girls is essentially equal.

Academic studies yield parallel results: in western classrooms, boys talk five times as much as girls, finds Allyson Jule, professor of education at Trinity Western University. So what accounts for this difference?

The root of the problem may lie in a phenomenon known as the confidence gap. Between elementary and high school, girls’ self esteem drops 3.5 times more than that of boys, the American Association of University Women found in a survey of 3000 students. Girls are told from a young age that being “well-behaved” means being quiet and polite, while for boys, being assertive is deemed more acceptable. The result: while males hold up their hands, females fall into the background.

Males are also more likely than females to be overconfident about an incorrect answer, according to a study published in the Journal of Educational Psychology. Admittedly, I’m complicit in perpetuating this disparity. Too often, I think I know the correct answer, but self-doubt weighs down my hand. When I do participate, my face turns red, and my voice comes out croaky.

This is not to say that males shouldn’t participate or that females should be forced to. Frankly, there is no obvious solution to this disparity. But at the very least, we should acknowledge that it exists and promote practices that target the root of why girls aren’t raising their hands, like discouraging teachers from ridiculing students’ contributions.

Interestingly, despite all evidence that says otherwise, a Black & White informal lunchtime survey of 15 females and 15 males found that 77 percent perceive that both genders participate equally, 16 percent perceive females participate more, and just two percent perceive males participate more. Although, it should be noted that all respondents who said females participate more identified as male.

This clash between perception and reality may possibly be attributed to variations in the number of males and females in a class. For example, in my four classes, three of them had dramatically higher male participation. The only exception was my AP English class, where twice as many girls participated than boys. The caveat? There are only seven boys in my class, meaning proportionally, males still participated about nine percent more than females.

The result of the gender gap in participation is a lack of appreciation for girls’ intelligence. Classmates and teachers assume students who don’t participate don’t know the answer, which is troublesome when boys are participating at dramatically higher rates than girls. A study of 1700 college students found that, on average, male students over-rank their male peers by more than three-quarters of a GPA point, and—even when their female classmates earn better grades—assume their male classmates know more about the subject, the Washington Post reports.

It’s time we become more cognizant of how gender plays a role in our everyday class discussions. Unfortunately, gender disparities enter the classroom alongside students—but let’s not perpetuate them.

Cole • Jan 26, 2018 at 1:16 pm

This article is poorly written. It attempts to turn the fact that boys raised their hands more in class into a sexist issue. It also shows sexism by mentioning that only the guys said that females partictpate more.

Lisa Cline • Dec 16, 2017 at 6:47 am

The author’s perception is a reality. See The Atlantic article, “The Confidence Gap.” Excerpts:

“Let’s look to the elementary-school classroom, the playground, and the sports field. School is where many girls are first rewarded for being good, instead of energetic, rambunctious, or even pushy. But while being a “good girl” may pay off in the classroom, it doesn’t prepare us very well for the real world. As Carol Dweck, a Stanford psychology professor and the author put it: “If life were one long grade school, women would be the undisputed rulers of the world.”

It’s easier for young girls than for young boys to behave: As is well established, they start elementary school with a developmental edge in some key areas. They have longer attention spans, more-advanced verbal and fine-motor skills, and greater social adeptness. They generally don’t charge through the halls like wild animals, or get into fights during recess. Soon they learn that they are most valuable, and most in favor, when they do things the right way: neatly and quietly. “Girls seem to be more easily socialized,” Dweck says. “They get a lot of praise for being perfect.” In turn, they begin to crave the approval they get for being good. There’s certainly no harm intended by overworked, overstressed teachers (or parents). Who doesn’t want a kid who works hard and doesn’t cause a lot of trouble? And yet the result is that many girls learn to avoid taking risks and making mistakes. This is to their detriment: many psychologists now believe that risk taking, failure, and perseverance are essential to confidence-building. Boys, meanwhile, tend to absorb more scolding and punishment, and in the process, they learn to take failure in stride. “When we observed in grade school classrooms, we saw that boys got eight times more criticism than girls for their conduct,” Dweck writes in Mindset. Complicating matters, she told us, girls and boys get different patterns of feedback. “Boys’ mistakes are attributed to a lack of effort,” she says, while “girls come to see mistakes as a reflection of their deeper qualities.”

Boys, from kindergarten on…roughhouse, tease one another, point out one another’s limitations, and call one another morons and slobs. Boys thus make one another more resilient. Psychologists believe that this playground mentality encourages them later, as men, to let other people’s tough remarks slide off their backs. Similarly, on the sports field, they learn not only to relish wins but also to flick off losses.”

Whitman Grad • Dec 14, 2017 at 3:53 pm

This “study” doesn’t seem to be much more than an observation that one author had… Publishing an article that jumps to conclusions off of such limited evidence is not only academically dishonest, but also dangerous.

Good Samaritan • Dec 21, 2017 at 9:21 pm

This “comment” doesn’t seem to be much more than a poor attempt to roast a student who simply published an article in a school newspaper… Publishing a comment that is so rude for so little reason is not only mean, but dangerous. #clapback

Louisa Wu • Dec 13, 2017 at 1:07 pm

Another issue for women is to actually be heard. I’ve been in meetings where a woman will suggest something that goes largely unnoticed, and then later on, when a man suggests *the very same thing*– it gets picked up in the conversation and widely lauded.