More than affirmative action: it’s time to stop minimizing minority students’ success

January 21, 2017

For many students, being accepted into college is a validation of hard work and dedication throughout high school. But my sisters had a different experience after they were accepted to Harvard; each heard others claim that she had “only gotten in because she’s Latina.” Around the country, other minority students—who benefit from often-controversial affirmative action policies—report hearing similar things.

One black Stanford student wrote in the Stanford Review that he felt that his acceptance came with an “asterisk”: it wasn’t just attributed to his intelligence and achievements, but also to his race.

Even as a junior, friends and classmates comment on the “advantage” that I will soon have in the college process. This comment perpetuates the idea that as a minority students don’t earn their acceptances to the same degree as other students.

This furthers negative perceptions of minorities, the opposite of the intended effect of affirmative action. Affirmative action, sometimes termed “positive discrimination,” refers to admission policies favoring racial and ethnic minorities that suffer historical discrimination.

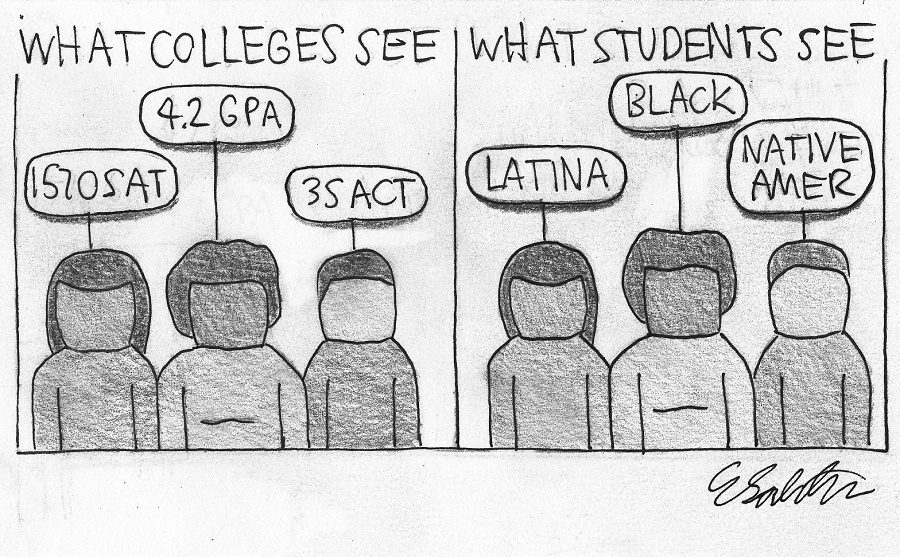

But reducing someone’s acceptance to their race or acting as if this is the only relevant factor in the admissions process minimizes other successes. Students with top grades, scores and impressive extracurriculars who just happen to be minorities are seen as nothing more than affirmative action admits, rather than deserving, talented individuals.

Not only does this mindset harm minority students, it’s frequently untrue. Affirmative action is often used in the selection of applicants with equal or comparable qualifications, according to research published in the Journal of Social Issues. This implies that if there are two qualified candidates and one is part of an underrepresented minority, the minority candidate would be selected over the non-minority candidate. In reality, selecting an unqualified candidate over a qualified candidate is against federal law.

Some claim that any advantage is unfair, but affirmative action is needed to rectify the historical underrepresentation of minority groups on college campuses—and it works. Since affirmative action became common in the late 1980s, college enrollment by students of color has increased by 57.2 percent, reports The Leadership Conference Education Fund.

These policies remain essential to ensuring diversity on college campuses. Carnegie Mellon—judged the “most diverse top college” by a 2015 Forbes article—is just three percent black, a disproportionate number considering that up to 15 percent of the nation’s population identifies as black. The statistics for Latino students are similar. Underrepresentation often makes it difficult for black and Latino students to find community at their college, a key part of the college experience.

Even if affirmative action policies feel unfair, suggesting that college acceptance of minority students is less legitimate is the wrong response to have.

The fact is, no one is admitted to college just because of race, ethnicity, or any other single factor. My sisters are Latina, and proud of it, but that’s not all they are. One won national writing awards and developed an expertise in acting, directing and researching Shakspeare; the other was one of the top female debaters in the nation and did extensive genetics research.

I witnessed their hard work and dedication, and I couldn’t have been prouder when it paid off. No student deserves to have their accomplishments minimized with an asterisk, and all should be able to feel proud of their acceptance without facing skepticism.

Angelique Wu • Feb 13, 2020 at 9:08 pm

Sorry, I don’t know how to reply to my own comment and make a thread, but one source that had similar opinions was this site. I’ve placed a link. https://www.toptieradmissions.com/assault-affirmative-action-unwarranted/

And a reason why I trust the author’s validity is because she was apparently an admissions officer.

Angelique Wu • Feb 13, 2020 at 8:59 pm

I have to comment, that as a Chinese American, the people I know are heavily against affirmative action.

To my knowledge, as well as theirs, affirmative action groups people into races and then colleges pick the best out of each race and then call it diversity. The reason I’m especially bitter towards this is because many a time I have come home with what I perceived to be good grades, only to have my parents rant at me on how it’s not good enough, since I’m Chinese. Because of this law, I feel that my personal achievements are minimized due to my race. Sure, I may not be top student, but I’m not bad. However, due to the labeling of my race, people judge me as “not good enough” as there are many other achieved Chinese people around me.

This is unfair for me as well. Why should I be judged according to someone’s perceived standards of my race? All for the sake of diversity. You mentioned that affirmative action is only used to pick when two people are fairly similar, but from what I’ve heard affirmative action can have a major impact on acceptance.

I don’t really understand your point of underrepresentation point. What does representation have to do with anything? Chinese as a race are represented pretty negatively by the news and often are at the end of subtle, yet damaging racism that few people acknowledge. However, they still work and get into college just fine. I myself am a person who believes that this advantage is unfair, but then again the legacies advantage is pretty unfair as well.

Certainly, your sisters definitely have great achievements though.

I’m open towards discussion, especially since your point of view comes from a fairly different one than mine, which will definitely broaden my information.

Lauren R. • Mar 2, 2017 at 8:38 pm

This is a well written article – Good job! Thank you for showing that people of ethnic minorities are accepted because of their academic accomplishments.

Lauren R.

http://birdeyenews.forrestbirdcharterschool.org/