Extended: Washington National Cathedral removes controversial Confederate windows

Charlottesville rally ignites debate over Maryland’s Confederate monuments

October 12, 2017

With its ornate exterior, stately columns and vaulted ceilings, Washington National Cathedral is an iconic D.C. landmark. Inside the self-proclaimed “Spiritual Home for the Nation,” architecture and American history merge: a moon rock fragment commemorates space exploration, a gargoyle pays tribute to Star Wars, and presidential imagery is abundant.

Perhaps most striking are the Cathedral’s 215 stained glass windows. Pastel light streams through the translucent glass, cocooning the Cathedral’s 400,000 annual visitors and casting streaks of light across the building’s interior.

But for the past 63 years, the Cathedral commemorated an unpleasant chapter in American history: two stained glass windows of Confederate Generals Robert E. Lee and Thomas “Stonewall” Jackson, who led the South during the Civil War, were displayed in the main level.

What makes this cathedral unique is that we don’t only tell a biblical story, but also an American story. You can’t talk about the Civil War without talking about slavery, and the windows made no mention of it.

— Kevin Eckstrom, National Cathedral Chief Communications OfficerThe Cathedral Chapter voted Sept. 6 to remove the Confederate-themed windows. They were extracted Sept. 8. The decision marks a critical turning point in a two-year debate involving authors, historians and religious leaders alike.

“[The windows] were a barrier,” the Cathedral’s Chief Communications Officer Kevin Eckstrom said. “People didn’t feel comfortable praying in that space with those two men looking over their shoulder. And ultimately, that is what the Cathedral is supposed to be: it’s a house of prayer for people and not a museum.”

After the Civil War, the Rebel Cause was euphemized and Confederate soldiers were glorified, African-American History Assistant Professor David Terry of Morgan State University said. To many, these windows were a physical manifestation of a prolonged admiration of the Confederate cause.

The United Daughters of the Confederacy donated the windows, which feature Confederate soldiers and a Confederate flag, in 1953. Today, they tell a distinctly Southern story, Eckstrom says.

“They were a whitewashed version of history,” he said. “What makes this cathedral unique is that we don’t only tell a biblical story, but also an American story. You can’t talk about the Civil War without talking about slavery, and the windows made no mention of it.”

After white supremacist Dylann Roof killed nine African-Americans at a Charleston church in 2015, Cathedral officials removed Confederate flags that draped the windows, igniting a debate regarding the memorialization of Confederate artifacts in spiritual settings. Following Charlottesville’s divisive “Unite the Right” rally Aug. 11-12, officials arranged the final vote. The windows will likely be placed in an educational setting, Eckstrom said.

A monumental debate

As a nation inextricably tied to slavery grapples with the resurgence of white nationalism, places of worship, civic spaces and national battlefields across Maryland face a divisive question: what to do with their countless Confederate monuments.

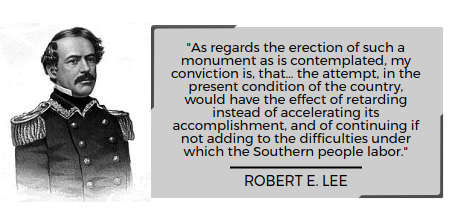

Author Jonathan Horn (’00) argues that rather than remove these monuments from public spaces, they should be contextualized with educational material. Horn spoke at a Cathedral panel regarding the windows this March. Horn’s book, The Man Who Would Not Be Washington: Robert E. Lee’s Civil War and His Decision That Changed American History, explains that Lee opposed Confederate monuments for fear of exacerbating regional strife.

“You can’t learn everything about a person like Robert E. Lee by just looking at a statue—you have to read a book to fully understand who somebody was,” Horn said. “Many of these statues don’t really commemorate the real Robert E. Lee; they commemorate the glorified image that wasn’t necessarily the real man at all. In many ways a Civil War monument tells you more about the people who put the memorial up than it does about the person it is supposed to honor.”

The purpose of Confederate monuments has long superseded honoring those they depict; many were intended to serve as physical reminders of white supremacy, Terry, who also spoke at the panel, said. Most statues were built during the Lost Cause, a Southern movement in the early 20th century that celebrated the valiance of the Confederacy while minimizing its connection to slavery.

By falsely claiming victory in the Civil War, the Lost Cause legitimized Jim Crow laws and institutionalized racism. In the 1960s, when Civil Rights leaders sought long-overdue equality for African-Americans, a new wave of Confederate monuments were built in bulk to intimidate them.

In the debate, location plays an important role. The National Park Service issued a statement vowing to keep Confederate monuments for educational purposes in its hundreds of parks and protected areas. In Maryland, Union and Confederate monuments will remain at Antietam National Battlefield, including a bronze statue of Robert E. Lee, National Battlefield Superintendent Susan Trail said. Because these monuments are located in a National Battlefield rather than a civic space, they present an educational opportunity, Trail said.

“To us, it’s really important and it’s an excellent way of conveying history by using the words and the material culture of people in the past to help us to understand them,” Trail said. “What would be lost would be opportunities for the public to gain some understanding by having physical objects they can look at and learn about.”

A predicament of lineage

For descendants of Confederate leaders and slaves alike, the events in Charlottesville inflame “generational guilt and generational trauma,” Kate Taney Billingsley said. Her great-great-great-great grandfather, Supreme Court Chief Justice Roger B. Taney, infamously wrote the majority opinion equating African-Americans with property and denying them citizenship rights in Dred Scott v. Sandford. The Maryland State House Trust voted to remove a bronze statue of Taney from the State House lawn Aug. 18. For Billingsley, the decision engenders a complex set of emotions.

Growing up, Billingsley said she felt both apprehensive pride and profound shame for her famous lineage. In March, her family publicly apologized to Dred Scott descendent Lynne Jackson in front of the Maryland State House. The two families advocated for the construction of a Dred Scott statue adjacent to Taney. Standing side by side, the two vastly different men would embody a symbolic reconciliation between their descendants, the families said. Frustrated by the removal, Billingsley is determined to install African-American figureheads at the State House, she said.

“Abraham Lincoln had slaves, and he is a hero in many ways. The money in your pocket—there are slave owners on that,” Billingsley said, “What’s missing is the hundreds of thousands of African-American people our country was built on the backs of.”

Billingsley and Jackson’s request, however, stood in stark contrast to that of the members of Our Maryland, a progressive education and advocacy organization. The group created an online petition Aug. 13 to pressure Governor Larry Hogan to remove the Taney statue. Before he decided to do so, Hogan called the movement “political correctness run amok.” Still, Our Maryland is disappointed in Hogan’s delayed response, spokesman Patrick Murray said.

“The governor reacted because he had to. It’s a little bit disappointing that it took him as long as it did,” Murray said. “Governor Hogan really had to be pressured into it by the citizens of the state. We are certainly glad that he finally reached the right decision, but that kind of delay on his part isn’t the leadership that Marylanders want.”

An uncertain future

What’s missing is the hundreds of thousands of African-American people our country was built on the backs of.

— Kate Taney Billingsley, descendant of Supreme Court Chief Justice Roger B. TaneyThe organization Sons of Confederate Veterans advocates keeping the monuments in place—not as an educational opportunity—to prevent what they argue is the rewriting of history. To history teacher Andrew Sonnabend, this argument is “ludicrous.”

“Rewriting history is not removing the monuments,” Sonnabend said. “It’s saying the Civil War was about states’ rights without acknowledging that it was about the states’ rights to have slaves.”

Sonnabend worries that the movement will evolve into a partisan issue. If the issue is reduced to a left-right debate, its critical importance may be lost, he said.

To Billingsley, from the Maryland State House to the National Cathedral, the monument removal movement will do little to contribute towards solving long term racial strife.

“It’s a good start, but I do not want us as a nation to get distracted by objects,” Billingsley said. “Taking down statues can make you momentarily feel proud. But then what do you do? I want us to realize that the system has put us this way and there’s a ton more work to do.”

A shortened version of this story originally appeared in Issue 1 of the print edition of the Black & White. Jonathan Horn was the Editor-in-Chief of Volume 38 of The Black & White.

Michael Horn • Oct 14, 2017 at 7:40 am

Great piece!

Ross Weintraub • Oct 12, 2017 at 8:00 pm

Great article. Very informative.