12

Why did you join the Black and White?

the clout. I also like journalism or whatever

What's your favorite scent?

a fresh magazine from a student-run, independent news organization

December 14, 2018

Students’ names have been changed to protect privacy.

In addition to learning multiplication and cursive, Liz Kleinrock’s third grade students at the Citizens of The World Charter School in Los Angeles, California, are learning about a more abstract concept: consent.

Kleinrock’s class defines consent as “saying yes to allowing someone to do something.” In a series of lessons, Kleinrock and her students establish situations when consent is necessary and review examples of what consent does and doesn’t sound like.

“If we’re lining up outside and somebody is putting their hands on you—whether that’s hugging, or pushing or grabbing something that belongs to you—learning how to say really firmly ‘stop’ or ‘I don’t like that,’ and for you to feel empowered and confident, is crucial,” she said.

Consent isn’t a new concept. But with the current national spotlight on sexual misconduct, highlighted by the 2017 #MeToo movement and Christine Blasey Ford’s recent sexual assault allegations against Supreme Court Justice Brett Kavanaugh, there’s an increased national push for consent education.

But for our generation, when we were as young as Kleinrock’s third graders—the time in our lives when we were beginning to formulate our perceptions of the world and ourselves—nobody thought to teach us these lessons.

Today’s teenagers are caught between two worldviews: the one we as a country are striving for, where consent is common, and the one we live with, where the voices of sexual assault victims are silenced and “consent” isn’t mentioned in any common core curricula.

I hope that our understanding of consent evolves alongside the former movement: that we learn how to say “no” to people and respect others’ boundaries. But this important lesson isn’t something we can learn through a few lessons in health class. Until society recognizes the complexity of consent, we can’t begin to change the toxic behavior surrounding it.

We engage in more casual relationships than our parents did, and while this isn’t necessarily harmful, more than a few consent “gray zones” accompany these relationships. Often, these relationships involve less communication, so feeling empowered enough to say “no” to uncomfortable situations is difficult.

During February of her freshman year, now-junior Sarah couldn’t wait to go to the annual Whitman dance marathon, Vike-a-Thon. But her expectations were shattered when she spent most of the four-hour event avoiding a boy who liked her.

Instead of making memories with friends, she spent the night feeling paranoid and hiding among groups of people or in the bathroom, not wanting to uncomfortably reject the boy but not wanting to hook up with him either.

“Concert culture” implies that anyone can hook up with anyone and that girls should anticipate this behavior. Saying no is an option, but that’s not always easy: Sarah herself couldn’t muster the courage to just tell the boy, “I don’t want to hook up with you.” Maybe she thought it would be easier to avoid him. Maybe she thought he might not listen.

“Anyone can go up to anyone and grope them or start making out with them,” Sarah said. “People can push them off and say no, but being a girl at these events, you kind of have to be on guard because there’s no regard for consent.”

Confidently saying no and expecting others to respect these boundaries is especially hard for teenage girls. In a Black & White article published last December about sexual harassment, reporters found that young people often misinterpret inappropriate sexual behavior as harmless. They may even think it’s desirable, researcher Jennifer Livingston said, because it’s the first time in their lives they’re receiving sexual attention.

This, combined with the fact that adolescence is a time when girls’ self-esteem is at an all-time low—clinical psychologist Robin Goodman found that girls’ self-confidence peaks when they’re nine years old—makes sexual attention exciting, even if that attention isn’t healthy.

Often, we don’t know a partner well enough to say “no” without it being awkward. A month ago, junior Anna hung out with a boy she liked. She said both of them basically knew they were going to hook up before she got to his house. But when they did, he immediately asked her to do something she wasn’t comfortable with. She stood up for herself and said no—but it was awkward. She felt guilty, so she agreed to do something else he wanted instead.

Trends like #MyBodyIsMine, a hashtag that circulated through social media on International Women’s Day last spring, assert that everyone has control over their body. That doesn’t mean it’s always easy to assert that right; even Anna’s confidence faltered in asserting her right to say no. But it’s not her fault. I blame our relationship with consent—and we can’t change it overnight.

Like many teens, Montgomery County teenager Maeve Kelly was appalled by the 2016 election, especially by then-candidate Donald Trump’s sexist remarks and sexual assault allegations. So her mom, Maryland delegate Ariana Kelly, proposed a bill in 2016 that would bolster consent education in MCPS. The bill, which the Maryland State Senate passed last May, will add age-appropriate lessons on the meaning of consent to all public, middle and high schools.

Some republicans and conservative democrats in the State Senate opposed the bill, which frustrated Kelly, she said

“To me, it’s common sense,” she said. “We are already teaching pregnancy prevention and STI prevention. That’s the more controversial stuff. This is just, ‘don’t do it if they’re not interested.’ It’s basic dignity and respect.”

Basic it is—so basic that Kleinrock’s third graders can grasp it. I like to think students understand the concept of “don’t do it if they’re not interested,” but understanding doesn’t necessarily translate to actions. After all, one in five women are victims of sexual assault while in college, according to a 2007 Department of Justice study, and I don’t think 20-year-old Stanford swimmer Brock Turner raped Emily Doe in 2015 because he didn’t know the definition of consent—he just chose to ignore it.

What’s more important than learning definitions is a moral education: teaching young people to respect their partners and giving them the tools they need to feel comfortable saying “no”.

At Whitman, the health course includes lessons on personal boundaries, healthy communication in relationships and how to define consent, health teacher Nikki Marafatsos said. Along with these lessons, Marafatsos brings in guest speakers to talk to students during the Family Life and Human Sexuality unit.

Junior Gabby Kisslinger took health last year. But she doesn’t think students learned enough about consent, she said.

“We mostly just talked about condoms and ways to not get pregnant,” Kisslinger said. “They touched on consent but not enough.”

But what would have been enough? A few more examples of what consent doesn’t look like? A larger emphasis on the importance of personal boundaries?

I’m not saying these lessons aren’t important—they’re definitely a step in the right direction. But people will still ignore consent. If everyone had perfect morals, the #MeToo movement wouldn’t exist.

The way we’re thinking and talking about these issues as a whole has changed; me writing this story is proof of that. When Kelly was growing up, the common perception was that girls never want to have sex and that it’s up to boys to convince girls to, she said. Now, she thinks and hopes this culture has changed.

“I’m the parent of a teenage daughter and an elementary school son, and I want both of them to know the importance of consent,” Kelly said. “The way we think about these issues has changed so much.”

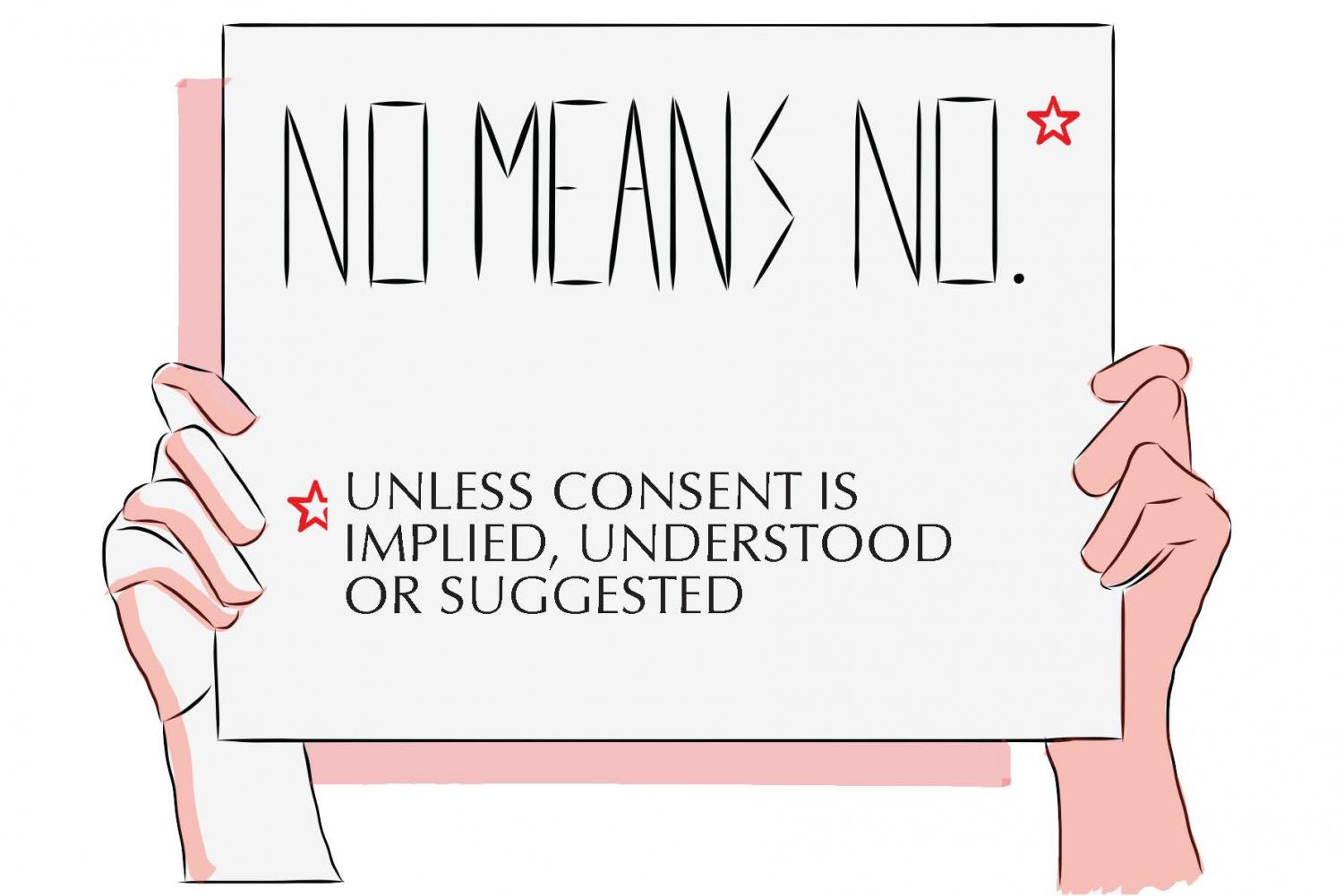

But the crescendo of consent awareness also makes the issue more confusing, with mixed messages coming from an onslaught of campaigns, from “Yes Means Yes” to “Time’s Up.”

Consent should be simple, and Kleinrock’s lessons show that. Her third graders probably couldn’t tell you the textbook definition of consent. But they know to ask their teacher for permission before they give her a hug. They know that they always have the power to say “no” if they aren’t comfortable with someone touching them or taking their things without asking. And they know that if someone says “stop” or “I don’t like that,” they always have to respect that without second thought.

They have years to practice those skills before they have to apply them to sexual consent. Hopefully, by the time they get there, they won’t feel like they have to spend the night of a school dance avoiding a boy or go along with their partners’ wishes because they would feel guilty otherwise. Hopefully, their partners will accept and respect a “no” in any situation.

“You can’t go back in time to change things that have happened,” Kleinrock said. “But students can learn social and emotional skills now to prevent them from getting in those situations later on.”