Fauci: ‘We are living through a historic experience’

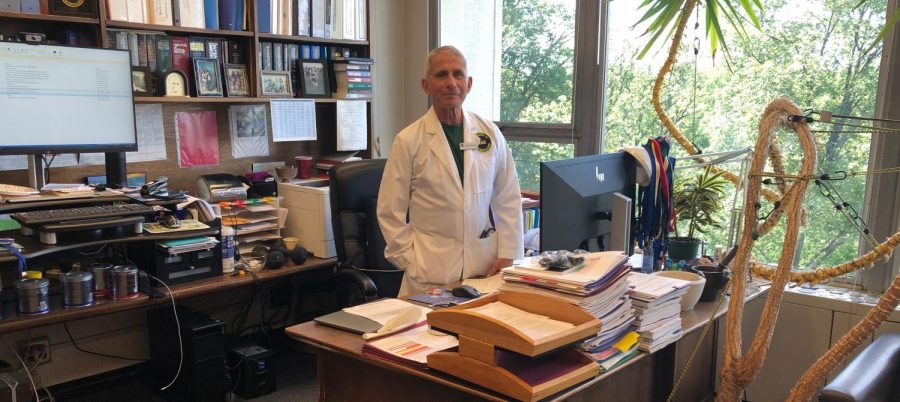

Dr. Anthony Fauci in his office at the National Institutes of Health.

June 7, 2020

COVID-19 has infected over 6.9 million people globally and 1.9 million people in the United States. As cases began to appear across America, state governments issued “stay at home” orders, and politicians and health officials have encouraged individuals to adopt social distancing practices.

The Black & White spoke with Dr. Anthony Fauci, Director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases and U.S. public health advisor. Fauci has served as head of the NIAID since 1984. He is a member of the White House Coronavirus task force and a public health advisor to President Donald Trump.

Responses have been edited for length and clarity.

Black &White: How are you doing?

Anthony Fauci: I’m fine. If you look back on the first months when things were very explosive, particularly when New York City was going through a really serious problem as well as New Orleans, my days became impossible. I was sleeping only three hours or four hours a day, which physically doesn’t work for more than a week. Then, I decided this was a marathon, not a sprint, so I chose to be a little more careful about remembering to eat, which I would forget to do because I would get so busy. Right now though, I can say that I’m doing pretty well.

B&W: Do you expect students to return to school in the fall?

AF: It depends on where you live in the country. Unlike some nations where everything is one dimensional, we live in a geographically vast country with a very large population. We have different situations in big cities than we do in intermediate cities and different situations in western and mountain cities. If you are in a region where there is still a considerable amount of virus activity, officials will either suspend physical presence in schools or, more likely, there will be some modification to schooling structure, namely a schedule modification. You may have part of the class in the morning and part of the class in the afternoon. You might have to stretch out the hours, come in on a Saturday or do more virtual learning— not completely virtual but some virtual learning— so you don’t have the typical situation of a crowded class. However, if things lighten up and the number of infections are low, something as simple as kids wearing masks when they are crowded together may work as a solution.

B&W: How close are we to having testing available for the school-age population nation-wide?

AF: I think we’re close. We got a slow start on testing because the first kits that came from the CDC were defective. We finally solved that issue, and now, I think we’re in a good place. I would hope that within the next couple of months, we will be able to test every student who comes into school, in order to at least know the baseline of who’s infected. After that, you can do things like screening and surveillance of a certain percentage of the class every one to two weeks.

B&W: What is the best way for students to stay safe during quarantine, especially over the summer break?

AF: You can enjoy the outdoors and the summer weather as long as you take certain precautions. Physically distancing, avoiding crowds of more than ten people, and washing your hands frequently will all help prevent infection. People think they have to stay locked in their houses, and you don’t. You can go out; you can walk; you can jog; you can do the things you need to do, so long as you leave a physical distance. When I go out, I always wear a mask even though 95% of the time, I’m six feet away from anybody outside. The fact is sometimes you turn the corner, and you’re in a situation where you find you’re very close to somebody. For that reason, you should have the extra special protection of a mask. Masks, distances, washing hands and no crowds — with that, you can have fun.

B&W: Mask-wearing has become politicized, with some seeing masks and other virus prevention measures as authoritarian. What would you say to Americans who don’t wear masks in public?

AF: Unfortunately, it has become politicized. If you don’t wear a mask, it’s a symbol that you’re in favor of opening up the economy and opening up society. I think those ideas are false narratives. The fact is you can be very much in favor of opening up the country and opening up the economy while still wearing a mask. I am very much in favor of trying to safely reopen America and get the economy going, yet I have no trouble wearing a mask. It’s unfortunate it has become a political issue rather than a public health issue.

B&W: The Pew Research Center recently released a report showing that only 60% of Americans believe that scientists should play a role in science-based public policy. What would you say to those who feel unsure about trusting science and scientists?

AF: This is an unfortunate situation because science is based on truth and evidence. It isn’t just confined to the United States though; we see this in many countries, including some well developed European countries. There is an anti-science sentiment that dates back to a mistrust of any authority because authority figures often abuse their power and take advantage of people. Since some people associate science with authority, the natural anti-authority feeling melts into becoming an anti-science effect. How can people be saying seriously they don’t trust scientists to be involved in making public health policy when public health policy is based totally on science? It is almost like an oxymoron. How could one say that with a straight face?

B&W: What comparisons can be drawn between the early days of AIDS and the early days of COVID-19?

AF: There are some strong similarities and some very strong differences. The similarities are that COVID-19 is a brand new disease that no one has experienced before. It is quite serious. It is transmittable from person to person. It can be deadly. The differences are that HIV/AIDS, from the very beginning, came upon us very gradually. The first cases were reported in the MMWR [Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report] 39 years ago. Yet the ultimate impact of HIV/AIDS was so insidious that we didn’t realize the extent of it and how many people would get infected. Thirty-nine years later, there have been almost 80 million people that have gotten sick, 38 million deaths and 6 million people living with HIV/AIDS. Those numbers are astounding, but they snuck up on us because they occurred over a number of years. In addition, HIV/AIDS are behaviorally related. There are certain subgroups of people who, because of their circumstances in life, are much more at risk than others. In contrast, the coronavirus exploded on us. It wasn’t subtle. Another thing that is extremely different is that everybody is at risk for coronavirus. It’s not based on any behavior but just by the very fact that you are breathing.

B&W: What do you want Americans to know about you?

AF: I am a very transparent, honest person. I am a scientist. I am a public health figure. I have devoted my entire professional life, to promoting, saving and preserving the health of not only the American public but of the world. My specialty is infectious diseases, and infectious diseases by their very nature are global threats. I want to encourage people to realize that we are living through a historic experience with COVID-19, and it is going to depend on all of us working together. We are all in this together. Nobody is exempt from this. This is something that involves all of us.

fauci stan • Jun 9, 2020 at 12:04 am

this is so cool and so important