Why did you join the Black and White?

I love writing and it's a great way to get involved in the community.

What's your favorite song?

Young Dumb and Broke - Khalid

In 1976, two Black & White reporters exposed a Soviet radiation scandal. Forty-four years later, we're looking back.

May 1, 2020

To a passerby, Rick Berke (‘76) and Michael Gill (‘76) would have looked like any other Whitman seniors going out for a quick meal at a diner in Bethesda in 1976. But they weren’t just any old high schoolers craving french fries or a chocolate shake — the two Black & White reporters were eagerly preparing for their interview with an anonymous government official.

During a trip to Moscow in 1959, then-Vice President Richard Nixon was exposed to high levels of radiation in what amounted to a Soviet assasination attempt. The American public was kept in the dark until Berke and Gill revealed the scandal in the April 1976 issue of The Black & White.

The official told Berke and Gill that for many years, the Soviets had been purposefully releasing radiation into the United States Embassy for “diabolical” reasons, likely leading to the deaths of numerous Americans who had stayed in the building and Nixon becoming exposed.

The CIA first caught onto the Soviets’ plan when agents didn’t detect any radiation in Nixon’s room during their prior security sweeps of the Embassy, but after Nixon arrived, there were deadly doses pinpointed in his room and bathroom. Berke and Gill were able to confirm through an Associated Press story that a U.S. ambassador who stayed in the same room as Nixon in the same year died of cancer. Additionally, an American employee at the Embassy died of Leukemia, and the U.S. Government compensated her husband because the death was considered work-related.

Sitting in the diner that used to be on the corner of Bradley Boulevard and Wisconsin Avenue, Berke and Gill could have never guessed the worldwide recognition their story would bring them.

Beginnings

It wouldn’t come as a surprise to anyone close to Berke that, while writing the story with Gill, he was also serving as the Editor-in-Chief of The Black & White.

His passion for journalism started at Bannockburn Elementary School, where he was an editor for the school newspaper. He went on to create and become the editor of the Panther’s Print, Pyle Middle School’s now-defunct student paper. After arriving at Whitman, Berke received special permission to be on The Black & White as a sophomore from the then-advisor Dr. Regis Boyle, the first time such a permission had been granted.

During his time on The Black & White — between 1973 and 1976 — Berke innovated many aspects of the paper. Most notably, he designed the current ampersand logo, ran the first color photos and added a feature section to the paper.

Michael Gill, Berke’s friend and the other reporter on the story, can’t remember exactly why he wanted to be on The Black & White in the first place, but he remembers his time on the paper fondly.

“It ended up being the main focus of my social life senior year,” Gill said. “We were together for the last period of the day, over the weekends and at the printers.”

Finding the story

How they came across the radiation story is more or less a mystery, Berke said. Berke, after many years, has forgotten the details of how it came to happen, and Gill chose not to disclose how it happened out of respect for the government official, who wanted to remain anonymous at the time. Berke guesses that Gill’s father heard about the story from the official and told him and Gill; however, Gill simply said that they found out about the story and asked to interview the official. The official figured it would be acceptable to share the story because enough time had passed since Nixon was exposed, Gill said. Berke and Gill then coordinated with the official to meet at the diner.

“There wasn’t any cloak and dagger to it whatsoever,” Gill said. “I think he even paid for whatever we ate.”

Berke recalled feeling differently during the interview. They were writing the story in the wake of the Watergate scandal, and All the President’s Men, a 1976 thriller depicting the exposure of the Watergate scandal, had just hit theatres.

“It was all very exciting,” Berke said. “At the time, people were all talking about investigative journalism.”

Berke and Gill don’t recall the process of writing the story all that well, but they both remember Boyle’s support during that time. Boyle gave them a lot of freedom and never questioned their source, Berke said. Instead, she focused on making sure it was well-written. Gill recalls her being well-known for her kind heart and blue hair, describing her as a “legend” who was “tough as nails.”

When it was time to send the newspaper to the printer, Berke decided to put the story on the third page of the issue. Berke said that his decision confused many people, who asked him why it wasn’t the front-page story.

“I was thinking as the editor,” Berke said. “I was saying, ‘We’re a high school paper. Why put an international story on page one?’”

In retrospect, Berke thinks he should have put the story on the first page, describing his decision as “kind of stupid” because of the story’s magnitude compared to the other Black & White stories.

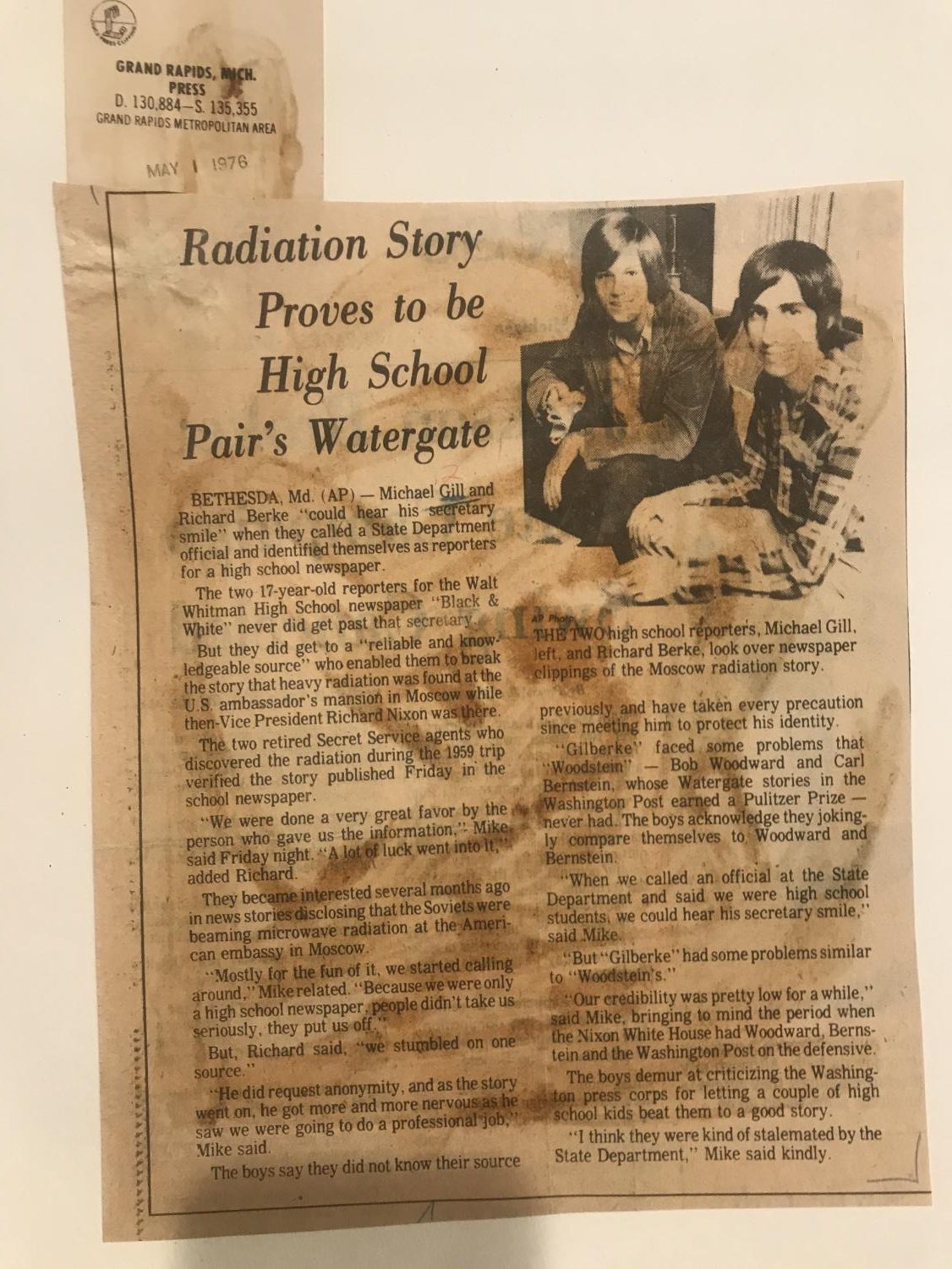

Shortly after its publication, the story caught the attention of the Associated Press; a reporter reached out to Berke and Gill for an interview. During their interview in Berke’s living room, Berke said the reporter noticed that Berke and Gill looked like junior versions of Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein, the two reporters that exposed the Watergate scandal just four years earlier. The reporter decided to send a photographer to take a picture of Berke and Gill, and that picture ended up in newspapers and magazines around the world. Almost all of the stories about Berke and Gill mentioned the similarities between them and Woodward and Bernstein, Berke said.

“I had the dark hair and Mike had blonde hair,” Berke said. “It was like a Dustin Hoffman/Robert Redford thing.”

But it wasn’t just newspaper articles about them that put them on the map. After the story’s publication, Berke and Gill appeared on a daytime talk show; a local documentary filmmaker nearly made a movie about them; and they received an award from the Local Chamber of Commerce.

Life after high school

Although Berke and Gill both look back on their story as a fun and exciting experience, both readily acknowledge that it didn’t alter either of their lives in a major way. Instead, it gave them memories and a cool story to tell.

Gill remembered that his former girlfriend’s parents, who lived in Denver, told him that they had read about him in their paper. For Gill, moments like these brought into perspective what he and Berke had accomplished and caused Gill to realize that the story was “a big deal.”

Ten years after the story appeared in The Black & White, Berke, a then-newbie reporter at The New York Times, overheard a national security reporter at lunch who said he had a classified document that said Nixon was exposed to radiation while in Moscow. Berke explained to the reporter that he had already broken the story in high school, to the doubt of the crestfallen reporter, Berke said.

Gill ended his journalism career when he graduated from Whitman and The Black & White. On freshman sign-up day at Villanova University, Gill decided he had signed his last byline when he found the students on the Villanova newspaper to be “jerks.” Since then, Gill has pursued a career in finance.

Berke continued on his journalistic path, writing for the paper at the University of Michigan and then taking on a nearly three-decade-long tenure as a writer and editor at the New York Times. Berke then co-founded STAT, a Boston-based health and medicine-focused publication, where he now serves as the executive editor.

“Really, everything I’ve done in journalism has been an extension of what I did in school,” Berke said. “I’ve just kept building on what I did on The Black & White.”

Even though Berke and Gill both admit that the story didn’t have a significant impact on their lives, they still feel a sense of pride when they think back to that experience.

“We were just these two plucky kids that ended up in the national press,” Gill said. “At the time, it was the biggest thing that had ever happened to us.”

Orion Hyson • May 1, 2020 at 2:03 pm

What a fascinating story!