Living with traffic: Montgomery County’s congestion problem

Traffic is a problem in the DC metropolitan area. Many teachers wake up early to avoid the rush hour.

Laughing along to a Comedy Central bit playing on the radio, gym teacher Joe Cassidy sits in his car on the ride from his home in Clarksburg to school. He’s been stuck in traffic on I-270 for an hour and 40 minutes, but after years of experiencing Montgomery County’s infamous traffic, he’s learned to adapt.

As is the case for many drivers in the area, getting to and from work is a daily endeavor for Cassidy. It’s a struggle typical of suburban areas like ours, but one that’s left experts puzzled over possible solutions.

Traffic keeps Montgomery County stuck

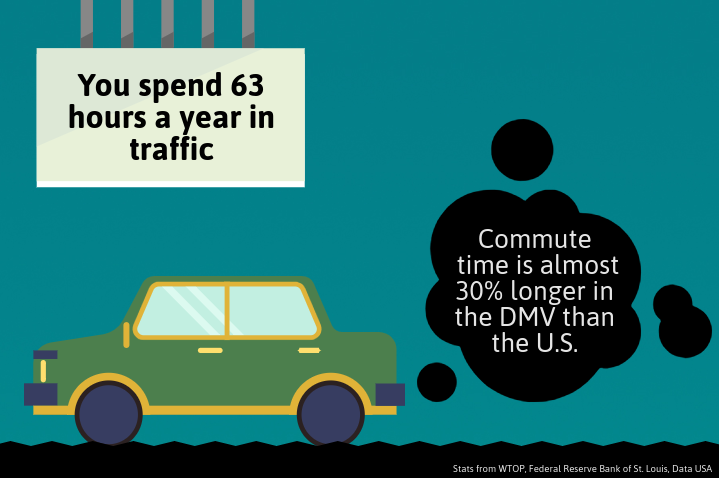

In the shadow of D.C., Montgomery County faces some of the worst traffic in the country. The county’s average one-way commute time of 35 minutes is significantly higher than the national average of 25 minutes, according to Data USA. In fact, the average DMV resident spends 63 hours a year stuck in traffic—one of the highest congestion rates in the United States.

As of 2017, rush hour commutes—usually between 3 p.m. and 6 p.m. in this county—are more than 140 percent longer than during off-hours on roads in and outside of the Beltway, according to a WTOP article.

“The worst indicators for traffic congestion are in this area,” said Cinzia Cirillo, professor of Civil and Environmental Engineering at the University of Maryland. “We are one of the richest, most densely populated area in the country, and we don’t have a very efficient public transportation system.”

Teachers and students have different experiences with traffic

Traffic affects the Whitman community heavily, especially burdening teachers who commute long distances to work.

Teachers are often left stuck in traffic for hours on end. To avoid the worst part of rush hour, many teachers leave school right after the final bell rings. Biology teacher Colleen Roots, who used to live in Howard County, said she was forced to leave Whitman early to avoid periods of long traffic.

“I could never stay after school and have a long meeting,” she said. “If I did, it would definitely impact my drive time. I didn’t stay for socializing.”

Teachers also often wake up early to avoid the brunt of rush hour traffic in the morning.

“I get up anywhere from 5:00 to 5:15,” Cassidy said. “On the flip side, now most nights I go to bed at 9:00. You just do everything earlier. You try to get home earlier; you have dinner earlier and you go to bed earlier.”

Assistant principal Phillip Yarborough, a Silver Spring resident, used to teach in Fairfax County, where he faced a commute of 2 hours and 40 minutes each day. Yarbourough said the shortened commute was a powerful draw factor for Whitman, since now his commute is only 40 minutes each way.

Traffic worries tend to be marginal for students, who for the most part live only a few miles away from Whitman. Junior Joanna Papaioannou drives to school, to her friends’ houses and to get food. For her, traffic is a rare, avoidable problem.

“I figured out how to avoid it,” Papaioannou said. “The worst traffic is usually on River Road around rush hour, and I just use the back roads instead.”

Traffic causes economic, environmental, and physical issues

Time spent stuck in traffic is time not spent working. As a result, congestion costs each Montgomery County driver nearly $1,700 per year—which adds up to $2.9 billion for the region’s economy as a whole, according to WTOP.

Traffic also damages our environment. With 28 percent of greenhouse gas emissions coming from private transportation, traffic inflicts serious harm on our planet, UMD’s Cirillo said.

The relationship between traffic congestion and health has also recently come under scrutiny. Recent studies show that traffic jams lead to higher rates of obesity, diabetes and poor air quality, not to mention worse mental health.

Drivers feel these effects. Art teacher Robert Burgess’ commute varies dramatically in the morning, from 30 minutes to an hour.

“Traffic creates a tremendous amount of stress every morning,” he says. “Not knowing whether one will be delayed impacts planning for first period and prepping for the rest of the morning.”

Politicians and policy experts look for solutions

Finding ways to combat traffic has become a must for any local would-be politician.

In hopes of reducing congestion, Gov. Larry Hogan proposed an $11 billion lane expansion plan, which seeks to add toll lanes on the Beltway and I-270.

Hogan’s proposal has been widely criticized by constituents as a waste of taxpayer money. A grassroots organization—Citizens Against Beltway Expansion—has sprung up in opposition to Hogan’s proposal. CABE co-chair and spokesman Brad German said he’s worried about the environmental and personal impacts of the expansion.

“Air pollution from cars, noise pollution and stormwater runoff will increase dramatically,” German said. “The plan would also add more than 600 acres of new impermeable surface, which will create a lot of untreated stormwater runoff that would be discharged into stream valleys and our stormwater management systems.”

Experts also see the proposal—which would likely require houses to be torn down—as a waste of time and money. They cite the economic principle of “induced demand,” which is the idea that adding more lanes will actually increase traffic because bigger roads will encourage more people to drive.

German also disagrees with the way this proposal was introduced; he said the process has been rushed and non-transparent, with some meetings taking place behind closed doors.

“The way this thing was rammed through just raises so many questions,” German said. “At the minimum, we need to take pause to find out more. At the end of the day, we’re just not very thrilled at the idea of tearing down homes for more Beltway.”

Another proposed solution to congestion has come from new county executive Marc Elrich. He advocates for reversible lanes on I-270, which would serve to aid congestion during rush hour.

While this policy has garnered more support than Hogan’s plan, critics say this measure isn’t an all-encompassing solution, and that it ignores the root of the problem.

“The reversible lanes will help, but they don’t solve the problem of congestion,” Cirillo said. “In transportation, there isn’t just one measure that solves the problem. You need to have different measures together in order to have a significant effect.”

Others suggest commuters pivot to carpooling or public transportation. The Purple Line will be built to connect Bethesda with Prince George’s County, with service projected to begin between late 2022 and 2024. Experts such as Cirillo and Dan Reed of the Greater Greater Washington Editorial Board believe that the new metro line will alleviate congestion.

But recent national trends show decreased use of public transportation. With low funding, increasingly expensive transit fees and unreliable service, few see themselves switching to public transportation. The contrast between the convenience of driving and the constraints of public transportation is a major reason why people drive, Burgess said.

“I have young kids,” he said. “If I need to get to their school—to pick them up early, emergency situations, doctor’s appointments—I need to be able to drive.”

Cirillo believes that the best solution is compact development, where housing, work, shopping and entertainment are all located in close proximity. For a suburban area like Montgomery County, such an approach may be a fantasy.

Although finding viable solutions has proven difficult, people remain committed to reducing traffic congestion.

“In the end, young people are not interested in owning cars or traveling by cars,” Cirillo says. “They want a different way of life, a life that is less dependent on cars, in which you have more public transportation services. We need to plan the future.”

12

Why did you join the Black and White?

The snacks

What's your favorite scent?

Rosemary

12

Why did you join the Black and White?

Because I wanted to get involved in creating graphics for the newspaper.

What's your favorite scent?

Lemons