What the gun control movement can learn from the teacher walkouts

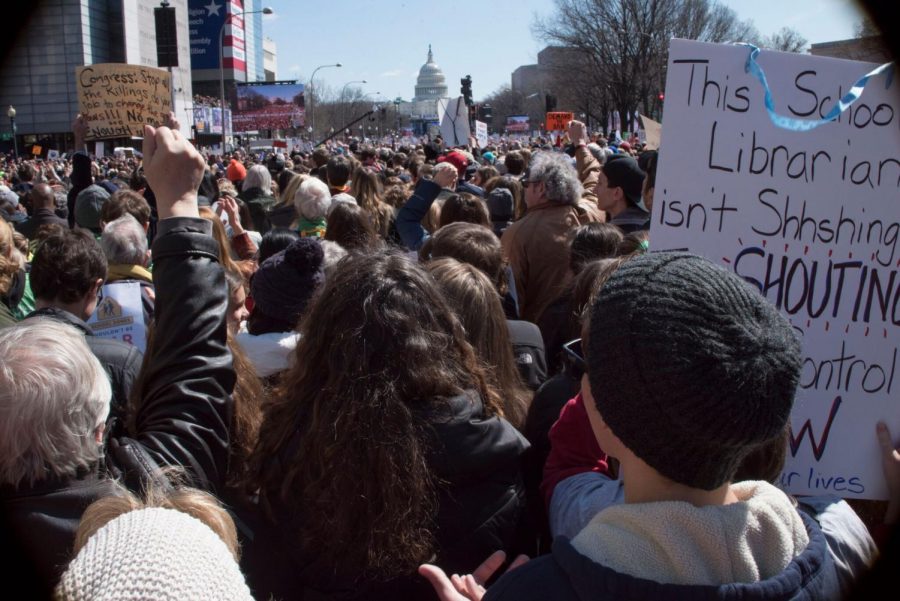

Thousands walk out March 24 for gun control, though legislation has not been passed since. Teacher strike movement has been more successful because the movement had clear goals. Photo by Annabelle Gordon.

June 4, 2018

This is a landmark time for student activism. Over the past two years, I’ve been to four marches on issues ranging from women’s rights to climate change to, most recently, gun control. As students growing up 15 minutes from DC, we’re privileged to be able to shout at Congress from its front lawn—but few of us can say we’ve contributed to concrete policy changes.

In terms of recent success, one particular protest movement stands out: the teacher strikes. West Virginia teachers got a five percent raise after nine days on strike, and Oklahoma’s state Congress passed a bill granting $6,100 raises. Arizona teachers got a 20 percent raise after six days, and teacher strikes in Kentucky and Colorado were also successful.

Unfortunately, other movements haven’t seen the same legislative success. The last action Congress took to fight against police brutality was passing the 14th amendment, and the recent push for gun control has been met with suggestions of arming teachers rather than changes to national policy.

So why have the teacher strikes had so much more legislative success than other recent social justice movements, and what can student protesters learn from their teachers?

One important factor is that schools grind to a halt when teachers refuse to teach. Nobody argues with the value of education, especially not politicians. By stopping schools, teachers force the government’s hand, and their demands are met in an effort to get them back in the classroom.

That’s really distinct from movements like the March for our Lives. While school stopped for a day as tens of thousands of students walked out of class March 14, the minor disruption was easily worked around. Some schools even made special accomodations for the event; Whitman went so far as to allot time for the 17 minute walkout in the bell schedule and excuse absences for students marching into DC. While these gestures allowed more students participate, they also diminished the disruptive impact of the protest.

To get the attention of politicians, student walkouts need to be more extreme. Teachers in West Virginia went on strike for nine straight school days, not one. For the same success, students need to leave schools for similar amounts of time.

It’s true that this is asking a lot of students, as there could be significant consequences for skipping this much school. But if we really want to achieve change, we need to take more drastic measures and refuse to go to school until it is safe to do so. After all, as minors with no voting power, our only real bargaining chip is our attendance.

Another factor that set teacher strikes apart was how clear they were to lawmakers about what they wanted as a result. Teachers in Arizona asked for a 20 percent raise. The state Congress was able to negotiate with them on the number, but they could still see an easy way to give the protesters what they wanted. The March for our Lives, however, has no concise policy-based mission statement, which makes it much more difficult for politicians to meet protesters’ demands.

There’s a pretty simple solution to this issue: the movement needs that mission statement. One popular option is a ban on assault weapons, but there are also calls for a more comprehensive background check system, or more security measures in schools. A bill calling for all of these would have no hope of passing, especially with our current Congress. To make it easier for politicians, student protesters need to stick to one objective at a time.

Students can make progress towards both of these necessities by organizing more coherently, and student run organizations such as the NASAGV need to plan events with these ideas in mind.

The point of protesting is to achieve policy change. If we as students are going to protest, we need to do so for longer and with clearer goals. Only then will politicians have no choice but to listen.

Natalie Keller • Nov 25, 2018 at 8:20 pm

This is a great article! Nice job Ted!!