Your scholarship money may not save you money

November 4, 2017

When an anonymous Whitman alum entered a music scholarship competition, he hadn’t received his financial aid package yet. He submitted recordings of a few songs and attended an on-campus audition, where panelists awarded three talented students—including him—$15,000 scholarships. But when his aid package came, it was lower than anticipated: $15,000 lower to be exact.

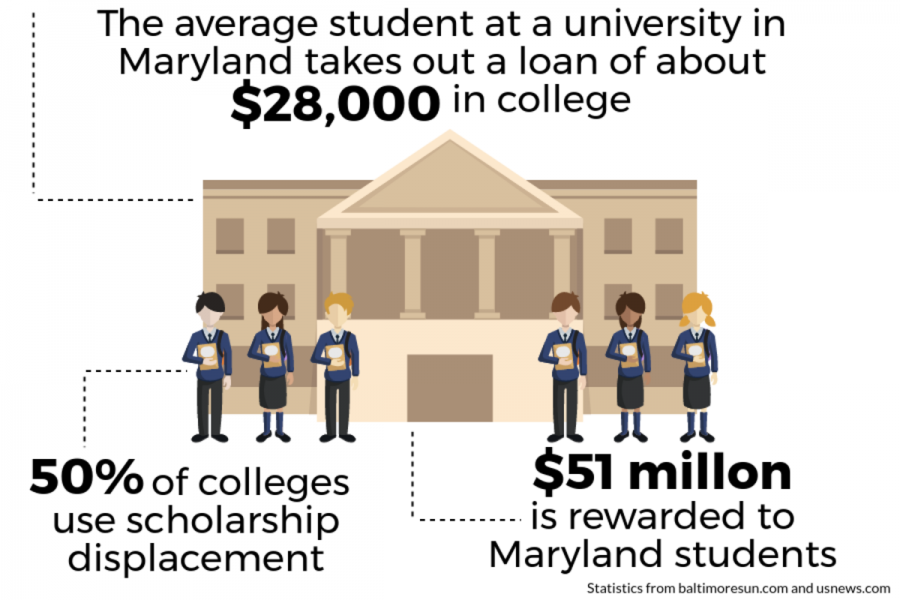

This student’s experience is not uncommon: 50 percent of colleges replace their financial aid money that doesn’t need to be repaid with students’ scholarship money, in a practice known as scholarship displacement, according to a survey by the National Scholarship Providers Organization. For this Whitman alum, the $43,000 in need-based aid he expected to receive from the college was reduced to $28,000 as a result of him winning a scholarship.

This past July, Maryland became the first state in the country to prohibit scholarship displacement at public universities. State legislatures should be applauded for supporting students’ pursuit of higher education. Now, state legislatures should take the initiative one step further: outlawing scholarship displacement at private universities in Maryland and at all schools across the country.

Financial aid alone often isn’t enough to afford college. The average student at a public or private university in Maryland takes out a loan of about $28,000 to pay for college, and across the country the average student walks out of college $37,000 in debt, the Baltimore Sun reports.

The disconnect between what students need and what a financial aid office is willing or able to provide is why so many choose to take advantage of a scholarship industry that awards $51 million to students in Maryland alone, according to Central Scholarship, a nonprofit that helps students afford college.

But these scholarship application processes are often almost as grueling as the college application process itself, requiring students to write essay after essay and send recommendation letters or audition tapes. Many students who don’t know about displacement work hard to win scholarships, only to later find out they’ve essentially won nothing, Sara Goldrick-Rab, a professor at Temple University who studies scholarship displacement, said.

The practice isn’t just financially and emotionally harmful to students—it’s also unsustainable for universities. Outside organizations will be deterred from giving scholarships if they know students won’t reap the benefits, Goldrick-Rab said.

Some universities claim they only have a limited amount of financial aid to give out and that the displaced money goes to students who demonstrate greater need than scholarship recipients. But there is no guarantee that the money will actually go towards needier students, and most colleges can afford to spend the extra money on aid, Delegate Dana Stein of District 11 and sponsor of the bill that outlawed scholarship displacement in Maryland, said.

Even if it comes at a small detriment to a university, individual students’ interests should be valued above a college’s finances. It’s unfair that a student who puts in the time and effort to win a scholarship could end up with zero net gain. A student’s hard work needs to benefit the student, not the institution. It’s time that lawmakers across the country ensure that scholarship money—intended for students—doesn’t end up paying for colleges’ needs instead.