Teachers: adjust rubrics to allow more creativity

June 7, 2017

The further I get in my educational career, the more I learn the importance of what I’ve deemed to be the golden rule of school assignments: follow the rubric.

The concept of a rubric is simple and well-intentioned: by giving students hyper-specific instructions for assignments, teachers can compare student work to fixed guidelines and track student improvement and growth.

But relying on rubrics comes at a price. Every time I do, I feel myself losing another fragment of my creativity. I stop using my imagination and generating my own ideas. Instead, I depend on the rubric to dictate my work. Thus, teachers and county officials should alter rubrics and school assignments to stimulate student creativity, incorporating more room for individuality and fewer restrictions.

Too often when I write for school, I find myself avoiding my own thoughts and writing what I perceive my teachers want to read based on the guidelines they give me. I never stray from the essay formula ingrained so deeply in my brain—lead in, quote, follow up, lead in, quote, follow up. Trying to experiment with assignments, at times, yields disappointing grades—often regardless of quality—when the product doesn’t match the standardized rubric. But when I follow the set path of a rubric, I end up mindlessly repeating what I know will earn me a good grade without attempting anything new or challenging. It’s nearly impossible to find a middle ground between strictly adhering to a rubric and using my individual thoughts and imagination.

When I was little, I loved to free-write in my spare time. It was easy to think of ideas by myself. I never wrote for a grade or to check off boxes on a graphic organizer.

Now, I don’t know what to do when I don’t have those boxes to check off. I’ve developed an over-reliance on guidelines. The ability to freewrite without a rubric’s burden let me think and imagine. But after years of cookie-cutter expectations, my imagination hits a wall every time I try. Without knowing exactly how many metaphors to include or exactly how many quotes to choose, I find myself confused about what to say. It feels like I’ve forgotten how to work without someone leading me through it.

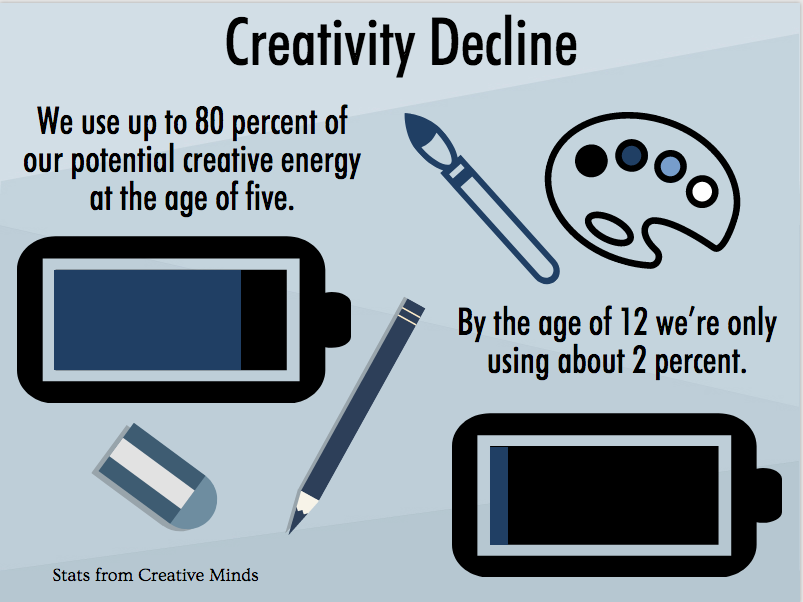

This creativity decline is dangerously normal for teenagers. We’re using up to 80 percent of our potential creative energy at the age of five, but by the age of 12 we’re only using about 2 percent, according to Creating Minds, a website that studies how to be creative and prevent creativity’s decline. Twelve-year-old kids are deep into their first year of middle school—a big year for students. They’re just learning to juggle assignments and homework. It’s the year that students really learn how to follow directions, write an essay and stick to a formula. And with that comes a formal introduction to conformity and an ominous farewell to childlike creativity. With so much at stake, schools, and especially middle schools, need to emphasize creative learning, not diminish it with mundane rubrics.

Designing rubrics that have fewer standards and more room for imagination would guide students, helping them learn and improve. Instead of giving students specific guidelines to structure their assignments (think: “creative” writing assignments that require students to artificially incorporate a multitude of different details), rubrics should aim to inspire an idea, and let students do the rest. Such strict guidelines create a dependency on instructions that is hard to shake later in life.

Some, however, argue that strict rubrics are necessary because they help teachers grade student work in an organized and objective way and tell students how to organize their work in order to receive a good grade. But this limits student learning with every assignment. Students learn how to impress teachers but not how to experiment and grow. Linda Mabry, a Washington State University professor, argued in a 1999 article that “compliance with the rubric tend[s] to yield higher scores but produce[s] ‘vacuous’ writing.”

Students need to use school as a time to grow and find their own unique voice rather than learn how to follow strict writing standards. Stringent rubrics make harnessing creativity difficult. Schools should alter rubrics to address the creativity crisis among students, allowing students to nourish their creativity and halt its seemingly inevitable decline.

stephen nyarko • Sep 23, 2020 at 6:14 am

I have really enjoyed reading your article. Thanks for sharing your thoughs with us. It is highly appreciated.

Good work.. Keep it up…